Rightsizing the 21st-Century Theological Library Print Collection

ABSTRACT: Natural sciences and humanities differ as disciplines in the types and age of material needed for research. Natural sciences require cutting edge, recent research while the humanities and social sciences utilize more dated material and primary sources. These differences consequently reflect different rightsizing criteria for the print collection. This article argues that similar differences exist in the disciplines represented in a theological library: systematic, historical, biblical studies, and practical theology, for example, and that these differences should be reflected in rightsizing decisions regarding the print collection. This article explores those rightsizing differences and delineates criteria for the biblical studies section in a theological print collection.

I recently read Pettegree and der Weduwen’s fascinating work, The Library: A Fragile History. The authors, known scholars in print and publishing history, trace the library from its beginnings in the ancient Near East as a status symbol for nations and the wealthy elite to the 21st-century public library, a fixture in communities worldwide. It is a fragile history fraught with the ravages of marauding and pillaging armies as well as the equally disastrous effects of natural occurrences like fire and mold. Throughout this storied history, “the essential problem [is] one that has not changed through the history of collecting, from Alexandria to the present: no one cares about a library collection as much as the person who has assembled it” (2021, 140).

After I had rightsized one section of our collection, an administrator said with a look of incredulity, “But you’re a librarian; you don’t get rid of books!” Is this a common misconception among faculty and administrators in higher education? Perhaps so.

“The idea that we are the chosen keepers of the sacred books is at odds with the fact that weeding actually goes to the core of the librarian’s professional responsibility to offer patrons the very best information possible” (Vnuk 2015, 2). Striking a balance between care for individual books and the stewardship of a healthy collection is challenging but essential. As historians, even Pettegree and der Weduwen (2021) recognize that “‘weeding’ is a core part of the librarian’s job and undertaken with seriousness while applying careful protocols” (406).

Furthermore, our accrediting standards require a curated collection. A collection that is never rightsized or weeded is not a curated one. By extension, one does not enter the librarianship profession, presumably, to indiscriminately hoard books. Instead, librarians are trained more so than most to recognize that not all books have equal value and merit in all collections. Additionally, in academic libraries, acquisition and de-acquisition decisions are based not on the whims of a reading public but in support of degree programs, curricula, and research interests of faculty and students.

The Association of Theological Schools recognizes the importance of librarians’ roles in curation in support of educational standards for the library: “Theological libraries are curated collections…” (ATS Commission on Accrediting 2020, 10). Curation involves not only attention to physical maintenance but also acquisition and de-selection decisions, both of which are better described by the word “rightsizing.” By definition, Miller and Ward explain rightsizing is a strategic, thoughtful, balanced, and planned process whereby librarians shape the collection by taking into account factors such as disciplinary differences; the impact of electronic resources on study, teaching, and research; the local institution’s program strengths; previous use based on circulation statistics; and the availability of backup regional print copies for resource-sharing. Rightsizing is determined by an individual institution’s mission, scope, priorities, and responsibilities; a “rightsized” approach for one institution might be too conservative or too aggressive for another. (2021, 8)

Taking just one of those factors (disciplinary differences) into consideration, librarians readily acknowledge that the humanities differ from other disciplines in the accepted age of resources. Keeping outdated resources “is a terrible practice in most other subject fields. Outdated information on medicine, law, and the hard sciences can mislead patrons” (Vnuk 2015, xix). However, few have recognized that the same differences occur within the disciplines of a theological collection. Even Miller and Ward (2021), despite their earlier definition of rightsizing, advocate a rightsizing approach that “is comprehensive and considers the collection as a whole rather than its parts” (49).

Consequently, rightsizing in a seminary library is best done discipline by discipline (historical theology, biblical studies, systematic theology, practical theology, to name a few) rather than applying one set of de-selection rules or criteria to the entire collection. This article focuses on the biblical studies section, elaborating on the rightsizing differences between this and other disciplines in a theological print collection.

Key Issues and Criteria for Rightsizing the Biblical Studies Print Collection

Institutional Context

The seminary library of which I have been director for fifteen years is no exception to the historical fact that “collectors always find it difficult to conceive that what they have curated, at great expense and effort, may hold little value to others” (Pettegree and der Weduwen 2021, 191). It is next to impossible for one who initially builds a library to realize that successive generations of scholars, students, and librarians might not value the books as he did—not out of malice but merely because books do not mean as much to individuals who did not personally select them. Moreover, as old research is superseded by new, the old becomes less pertinent to succeeding generations. The William Perkins Library, at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, was initially developed from the personal libraries of two individuals, one of whom is a true modern-day bibliophile. However, many books, primarily in the biblical studies section (BS classification), had become outdated in their research or less relevant due to their purely devotional content. Although I regularly practiced discarding titles as part of my routine duties, I had never undertaken an extensive section-wide rightsizing project.

I used the following criteria with the BS print section: core faculty involvement, age and relevance of material, circulation data, and online availability. Apart from the first criterion of faculty involvement, the remaining criteria vary according to theological discipline, as noted above, and may even differ from one seminary to another. I utilized WIDUS criteria without necessarily realizing or intending to do so because it is a commonsense approach and works well for the needs of the biblical studies discipline (Vnuk 2015, 6). The WIDUS acronym represents the following de-selection criteria: worn out, inappropriate (for the particular collection or institution), duplicated, uncirculated, and superseded.

Core Faculty Involvement

Faculty are crucial stakeholders in theological collections, and, out of respect and appreciation for their knowledge of the subject material, librarians should give them a voice in any rightsizing project. The final decision, however, should be in the hands of those who curate the collection. Faculty and administrators must acknowledge that “no one knows a collection as well as the librarian or archivist who curates it” (Pettegree and der Weduwen 2021, 415). While they may know parts of it very well, the librarian-as-curator knows the whole and has a finger on the pulse of degree programs, research interests, and curricula of the institution, as do few others.

A June 2023 two-item survey regarding the role of faculty input in rightsizing decisions yielded an encouraging response from the thirty-one seminary librarians who responded from across North America:

- Item 1: Every librarian has the ability to discard/withdraw/de-acquisition titles from the seminary collection as needed, with the understanding that professional guidelines are used and decisions are made that best support the degree programs. (Unanimously affirmed.)

- Item 2: Faculty input is not required and is only requested as needed at the librarian’s discretion. (All but one affirmed that faculty input is not required.)

Perkins Library’s PhD program director, a published biblical studies scholar and an Old Testament (OT) faculty member, was entirely on board with an extensive rightsizing project of the entire BS section, and 10,000 to 15,000 volumes were eventually de-selected. He was the point person, initially culling volumes title by title from shelves and handing them off to me to make the final decision and remove them from the catalog. I respect his scholarship and research abilities, and took his de-selection suggestions seriously. Neither of us, I might add, tends to hoard books, which greatly aided us in making the necessary decisions. Personality does play a role in how efficiently de-selection activities are handled.

An essential component in our rightsizing project was that the OT professor intimately knew the subject matter, and I intimately knew the collection, degree programs, and student use. We are a two-person seminary library. I work at the circulation desk all day, every day of the week. I know what the students are using and checking out. I see every syllabus each semester. I make a point of knowing the scholars and important publishers in each discipline within the seminary curriculum, as well as the research interests of the faculty and doctoral students. Fifteen years of accumulated knowledge was brought to bear on each title that went through my hands. Knowledge of one’s collection, curriculum, and users cannot be overemphasized and is indispensable in rightsizing activities.

Age and Relevance

I am always learning more about the disciplines our degree programs represent: important scholars and upcoming ones, debated themes, and essential titles in each theological category. As an example, about three years ago, I learned that our biblical studies professors on both the master’s degree level and in advanced studies discouraged students from using print commentaries more than fifty years old due to their irrelevance. I could immediately envision my historical theological friends protesting in alarm. However, this difference in perspectives emphasizes an essential distinction between the disciplines of historical theology and biblical studies. By necessity, historical theological scholars act quite differently toward older material than biblical studies researchers do. This difference is even noticeable in dissertations from the respective disciplines. Historical and systematic dissertations and theses tend to divide bibliographies into primary and secondary source materials. In contrast, research in biblical studies and practical theological topics divides bibliographies into articles and monographs, emphasizing attention to dated materials in one and not in the other.

Biblical studies more closely resembles the natural sciences in its perspective on the age of source materials. Current research, critical studies, and commentaries are more important to ongoing scholarship than 19th-century or early 20th-century material. A student engaged in systematic theological research might trace the development of a doctrine across a particular chronological era or within a specific group, whereas biblical studies research involves engaging current critical material. Even in lower-level degree programs, recent commentaries are preferable because they reflect developments in linguistic analysis, textual criticism, current debates, and cultural applications that older ones do not. If you doubt this preference reflects that of your institution, try an informal survey with your faculty. How many of them favor students citing a commentary from the 1860s in an exegetical paper? How many faculty supervising doctoral students accept a dissertation bibliography that includes commentaries or textual criticism from 1920 or even 1950? When evaluating collections, librarians must not fail to note that theological disciplines vary in how they deal with older material. Recognizing that fact is critical as seminary librarians approach rightsizing.

One reason biblical studies faculty favor more recent material may be that many 19th-century commentaries are highly devotional in content and sometimes lean toward allegory and symbolism. The University of Chicago Divinity School’s collection development policy represents that of many theological collections when it states that devotional materials are among the items excluded in acquisition decisions (University of Chicago Divinity School, n.d.). Very few of these resources are necessary for retention in a seminary library. In contrast, the BS section at my institution consisted primarily of such dated devotional material before rightsizing.

In addition to thousands of 19th-century commentaries, the section contained lay-level material, popular titles, and sermon tracts published in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. These volumes also met the low circulating criteria (see below). They were simply not relevant, useful, or appropriate for master’s level or advanced studies programs nor the research interests represented in our institution. An interesting anecdote illustrates the de-selected volumes’ lack of relevance: a faculty member, a librarian (yours truly), and students (both doctoral and master’s-level students) all looked through the volumes selected for de-acquisition. I allowed the students to take any books they wanted1. Almost no one took any of them (0.05 percent were taken). The low percentage of de-acquistioned titles confirmed the relevance factor and circulation statistics. For administrators and faculty who are overly cautious or strongly opposed to any de-selection processes, it may be helpful to remind them that the theological collection “is not a museum—there is simply not enough space (nor is it a library’s mission) to be a warehouse of unused books” (Vnuk 2015, 2).

I have observed students who select 19th- and early 20th-century commentaries because they are enamored with old books and think using them will impress the professor. Recently, an international student came to check out books for an Old Testament introductory course paper with a late 19th-century title in her hands. She said, “I need primary sources; this is a primary source, right?” An immediate split-second internal conversation followed: You explained that at length in last fall’s research course that she was in; note to self: clarify and elaborate on this further the next time you teach this course.

Regardless of my culpability in this student’s misunderstanding, it emphasizes librarians’ roles in keeping relevant materials on the shelf. This is another way we fulfill our mandate of curating collections. A curated collection provides users with appropriate resources in each section so those who know the suitable sources can easily find them without sifting through irrelevant material. Those who do not are pointed to appropriate titles by what is on the shelf. The browsable shelves can then serve to “highlight…those materials that continue to be highly preferred or exclusively available in print” (Miller and Ward 2021, 34).

An essential caveat to dated materials in a biblical studies collection is a subcategory that is experiencing growing interest. Reception history traces how biblical texts have been viewed and interpreted from the patristic period onward. Students and researchers studying reception history need access to dated material. Consequently, primary sources for Second Temple Judaism studies and early Jewish interpreters of biblical texts are important for advanced studies research regardless of the material’s age.

A final caveat is that many theological collections include titles of denominational or local historical importance regardless of whether they support a specific degree program. Often, these resources are best kept in a separate section or as a separate collection. Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary has a collection of antiquarian titles by English and American Puritans and Dutch Second Reformation theologians. These are kept in a separate climate-controlled room for their maintenance and to provide clarity for our users. Within the general circulating collection, the biblical studies faculty member and I retained print titles written by figures historically important for our Dutch Reformed and Puritan focus and heritage, regardless of the material’s age. Each seminary has its denominational niche with correspondingly important theologians and historical figures, and considering this when rightsizing is essential irrespective of the specific section or discipline being evaluated.

Shelf Space

Rebecca Vnuk offers both parameters and benefits for de-selection efforts, in The Weeding Handbook: A Shelf-by-Shelf Guide:

- In most libraries, the shelves should ideally be 75 to 85 percent full. This makes the items much easier to browse, makes it easier to shelve, and, in general, makes the collection look better. But it’s not only looks that matter—it also saves patrons time and frustration. When outdated materials are removed, then newer, more frequently used materials become clearly visible on the shelves. Who wants to search through a dozen outdated or ragged books to find the one they are really looking for? (2015, 1)

Expanding on Vnuk’s above recommendation, I prefer to leave at least ten inches of growth room per shelf. Although this approach leaves each shelf closer to 70-percent full, it works well for growth rate and suits my preference for the collection’s appearance. Considerations such as growth rate and individual preferences are unique to each library and should be balanced with more general guidelines. Before the rightsizing project, our shelves were packed without growth room for new and relevant research in biblical studies, providing the impetus for our efforts. The seminary’s biblical studies doctoral program was several years old, and with specialized doctoral research came new acquisitions and new recommendations. The library’s resources on Matthew, John, Romans, Revelation, Paul, and biblical theology were growing with exciting new titles. Still, each new book brought the challenge of shifting existing books to make sufficient room. The overstuffed shelves rendered browsing, selecting titles, and shelving books challenging and frustrating.

One of the values instilled in me by my undergraduate work in an academic library is the physical maintenance of a library’s primary resource: its books! Effectively maintaining print collections requires protecting each volume’s condition and preserving the collection’s appearance. Packed shelves trap humidity and increase the risk of mold, so I encourage student workers to give the books “room to breathe” by avoiding tight compression as they shelve. Edging and straightening each shelf several times a year also contributes to the well-being of individual volumes and the overall appearance of the collection. These efforts facilitate efficient scanning during inventory, help locate slim volumes that have slid behind other books, and allow me to identify any areas of the collection that need particular attention. Continued maintenance enables me to have eyes and hands on the collection and provides an opportunity for me to improve its condition, appearance, and browsability.

These considerations also reflect the importance of aesthetics as an undervalued characteristic of a well-maintained collection. I strive for a collection whose appearance is attractive to match a classical, welcoming library atmosphere. God made us to appreciate that which is beautiful, orderly, and symmetrical. In contrast, “crowded shelves and worn-out books are distasteful, especially to busy patrons” (Vnuk 2015, 2). Thirty-five inches of books squashed together on a shelf is not a thing of beauty for the eyes or the end user.

Circulation

Miller and Ward (2021) note, “Today, circulation statistics are still a part of the process for identifying withdrawal candidates, but they are now only one of a wide array of factors that librarians take into account” (40). One of the criteria we used for discarding titles in the BS section was the number of times a title had been checked out. Ninety-nine percent of the titles had been used fewer than three times in the last fifteen years, and of that 99 percent, the majority had zero checkouts. Our library does not have the capacity to retain books that are unused by current students and faculty, and there is no compelling need for us to do so. “In the case of major research universities that may also serve as regional supplies or consortial leaders, it may make sense to build and maintain a state-of-the-art library storage facility containing virtually everything the library ever purchased that is not currently enjoying fairly high use” (47, emphasis mine). Thankfully, theological librarians and their seminaries can confidently look to these larger institutions, which are taking the necessary, expensive steps to preserve and back up historical records on servers. It should be noted that “many storage facilities see circulation rates of 2 percent or less per year.” In light of this, administrators would do well to support and encourage “librarians to channel their abilities for selecting the right items to store into strategies for identifying the right items to withdraw” (48).

Online Availability

Another consideration criterion was whether nineteenth-century titles selected for de-acquisition were available online. In partnership with Internet Archive, Princeton Theological Seminary had already digitized the books we withdrew. Consequently, we did not need to keep copies for the historical record. On a related note, I regularly enhance our nineteenth-century historical theological and systematic titles by adding the Internet Archive link for Princeton Theological Seminary titles to print bibliographic records.

In summary, books from the biblical studies section were removed with faculty input and by using professional best practice guidelines for the biblical studies section in a theological seminary. All of the titles we withdrew met the following criteria:

- Zero to three checkouts since 2008, when the collection was first cataloged

- Available online (Princeton Theological Seminary records in Internet Archive)

- Not a historically significant author

- Outdated research-wise for the discipline

- Popular-level or devotional material, not seminary-level material

The discarded books were either given to our seminary bookstore or sent to Better World Books to sell.

What about Other Disciplines?

The successful completion of the rightsizing project for biblical studies provided an opportunity for conversations about the priorities that guide collection management in other theological disciplines. For example, in our discussion about rightsizing the systematic theology section, the primary faculty member for that discipline indicated that he would remove some titles but not as many as were removed in the BS section. Systematic theological research tends to mirror historical theology in that it traces doctrines across eras in church history and often deals with the theology of historical figures, which renders access to primary source material critical. My experience and observation have confirmed that, when possible, scholars and advanced studies students in systematic and historical theology prefer to work directly with print primary source material in research. This sort of awareness is crucial for making de-selection choices for the collection.

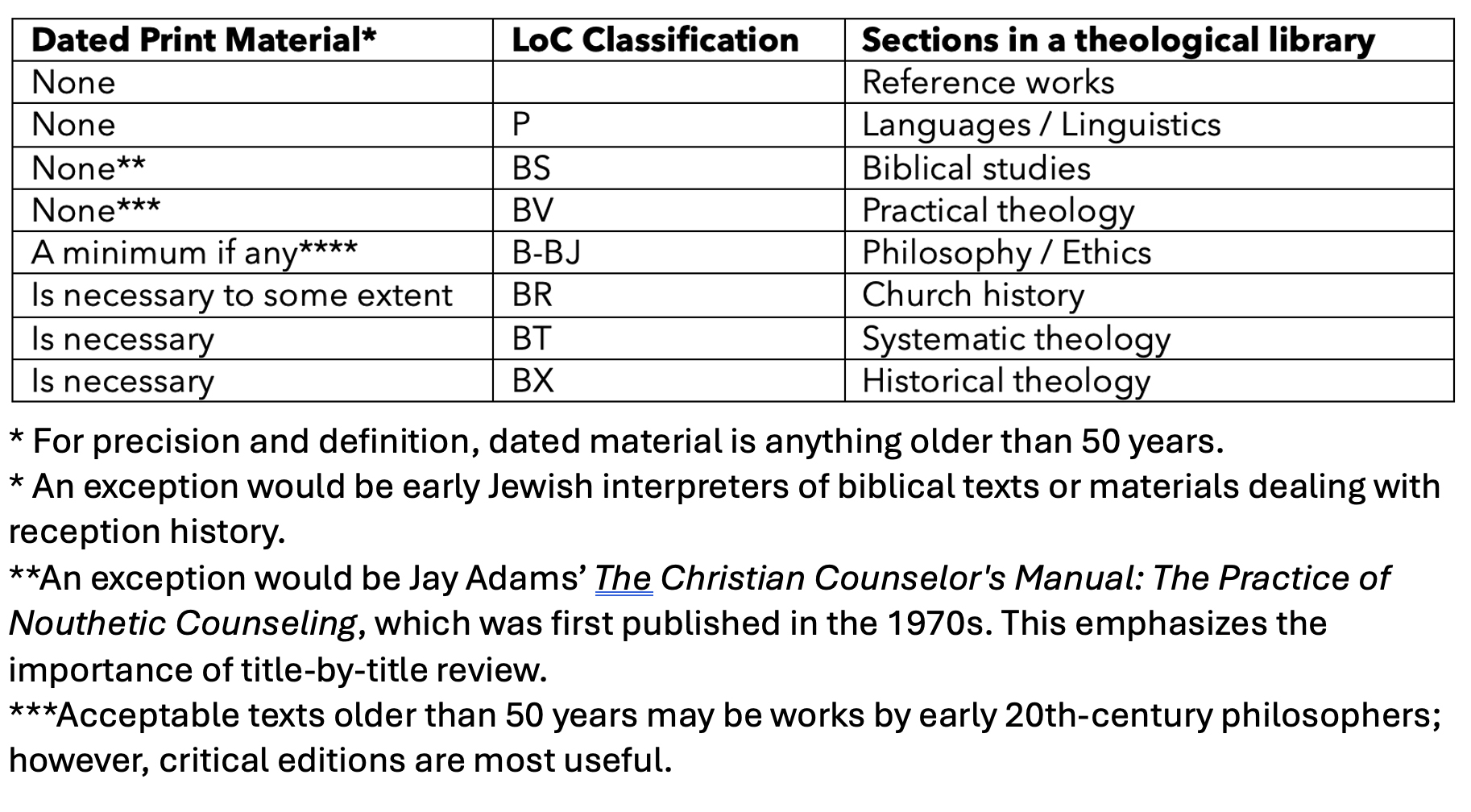

In contrast to historical and systematic theology, practical theology more closely resembles biblical studies in that current research on religious education, counseling, preaching, and spiritual formation is required. For ease of reference, the following chart reflects my recommendation of the extent to which each discipline in a theological collection should contain dated print material, moving from none to its necessity:

[IMAGE 1 – Table of Theological Subcategories]

Conclusion

In their introduction to the fragile history of the library, Pettegree and der Weduwen (2021) make the following insightful observation: “Even if libraries are cherished, the contents of these collections require constant curation, and often painful decisions about what has continuing value and what must be disposed of” (3). Rightsizing decisions for the print collection are best made by bearing in mind the different research needs reflected in the varying disciplines of a seminary. This includes being cognizant that biblical studies, as a discipline, primarily relies on current research. In contrast, systematic and historical theological research depends to a significant degree on dated primary source print material. Making and communicating decisions based on these differences should help the broader professional community of theological librarians with the delicate and often emotionally charged situations surrounding rightsizing a print collection. I hope this article contributes to the discussion at other seminaries and promotes healthy theological print collections for 21st-century theological education.

References

Association of Theological Schools. June 2020. “ATS Commission Standards of Accreditation.” https://www.ats.edu/files/galleries/standards-of-accreditation.pdf.

Miller, Mary E., and Suzanne M. Ward. 2021. Rightsizing the Academic Library Collection. Chicago: ALA Editions.

Pettegree, Andrew, and Arthur der Weduwen. 2021. The Library: A Fragile History. New York: Basic Books.

University of Chicago Library. n.d. “Collection Development Policy: Religion.” Accessed April 19, 2024. https://guides.lib.uchicago.edu/c.php?g=297396&p=1992070.

Vnuk, Rebecca. 2015. The Weeding Handbook: A Shelf-by-Shelf Guide. Chicago: ALA Editions.

Notes

1 The books made available for the students to take if desired were specific seminary-owned titles,not those from the primary donor whose books served to begin the seminary collection. This is an important distinction in this context.