Queer Religious Representation on Wikidata:

Complexities, Challenges, and Possibilities for Data Creation/Repair

abstract: Queerness defies easy description on knowledge graphs. The fluidity and sensitivity of queer identity is often poorly represented by rigid ontologies with hetero-cis-normative guidelines that do not lend themselves to accurate queer representation. Nonetheless, engagement with mainstream knowledge graphs like Wikidata can provide opportunities to improve discoverability of queer histories and experiences, which are often hidden in the archival record. These efforts may be particularly important in spaces where queerness is often unrecognized, such as religious studies. In order to measure the effectiveness of queer religious representation on Wikidata, I conduct a basic statistical analysis of the Wikidata identifiers corresponding to the profiles listed on the LGBTQ Religous Archives Network. Building off this data, queer theories of metadata, and social justice-oriented WikiProjects, I identify gaps in Wikidata representation and suggest ways to interrogate and potentially repair these absences in the metadata.

Objectives

The aim of this essay is to compile data about the representation of queer religious individuals in the LGBTQ-RAN dataset on Wikidata. I begin by giving a background of the challenges of representing queerness in data ontologies. I specifically look at the ways that the representation of queerness has been contested and defined by Wikidata users. I then discuss the importance of repairing metadata to better represent queer individuals and queer religious individuals specifically. I briefly examine projects that contribute to this goal, including LGBTQ+ Religious Archives Network, the Women in Religion and LGBT WikiProjects, and Homosaurus. Having established a basis for my data collection, I present my methodology for collecting data on queer religious representation on Wikidata and summarize my results. This data is placed in discussion with debates about queer metadata to determine how representation may be improved in the future.

The data I compiled is not only intended for this essay, but also as a living document that editors can use to improve Wikidata representation themselves. To this end, the appendix containing the data used in this study is designed with community usage in mind. The data table is the table used in “FAIRly Obscure: An Edit-a-thon Exploring Anthropology, Communities, and Wikipedia Representation.” The FAIRly Obscure spreadsheet is used in classroom and edit-a-thon settings to allow participants to choose Wikidata identifiers and Wikipedia articles to create or improve, with a focus on indigenous anthropology. I am also influenced by Baker and Mahal (2024, 219) in examining the representation of marginalized communities on Wikidata through the case study of a focused dataset, rather than examining the entire knowledge base. This limited approach allows for a narrower view of a particular intersectional identity while creating a smaller dataset that can be more easily used to create immediate improvements in data representation.

Background

In representing queerness on Wikidata, users must confront conflicting priorities and notions of queerness within a limited knowledge graph. LGBTQ individuals have historically been underrepresented and/or rendered absent in knowledge bases, linked data schema, and archives (Freeman 2023, 459). Attempts to represent and preserve queerness have existed both in and outside of traditional archival settings. Because of the fluidity and embodiment inherent in the queer experience, it is not always easy to place queerness within a controlled vocabulary or catalog. Some scholars have even argued that it is counterproductive to attempt to do so (Schram 2019, 612-614), (Stahl 2024, 24). Others have focused on the potential of recording queer history and experience in non-traditional archives, such as the Digital Transgender Archives or community archives. These “archives” may not fall under industry-standard definitions of archives, but may be better suited to representing queerness (Rawson 2018, 329) (Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge 2013, 297). Still, many people see a role in attempting to represent queerness in mainstream metadata, like Wikidata. The invisibility of queerness in metadata, which creates invisibility in archives and catalogs, hinders the exploration and expression of queer history and experience (Freeman 2023, 466). Improving this data could create new understandings and possibilities of queerness. (Morris 2006, 149)

There is clearly interest in using data schema to improve the discoverability and representation of marginalized communities. A statistical analysis of articles about the use of Wikidata in libraries found that 29% expressed “social justice” as a motivation behind adopting Wikidata in the library (Tharani 2021, 5). In their chapter “Toward a Queer Digital Humanities,” scholars Bonnie Ruberg, Jason Boyd, and James Howe claim that digital tools and digital humanities have “the unique capacity to make visible the histories of queer representation and issues affecting queer communities,” (Ruberg, Boyd, and Howe 2018, 108). They specifically mention linked data as a particular manifestation of this digital humanities. Linked data and digital archives present the opportunity to connect queer-operated digital humanities projects to more mainstream knowledge graphs to increase their reach and visibility. For example, Homosaurus, a queer linked data ontology, can be implemented across controlled vocabularies, and now has a property on Wikidata (P13438). External vocabularies like Homosaurus present opportunities for more accurate and culturally sensitive descriptions (Dahl and MacLeod 2023, 3). By including these data ontologies on a central hub like Wikidata, queer communities can expand the reach of queer data description.

There are two primary ways in which queerness is denoted on Wikidata: P21 (sex or gender) and P91 (Sexuality). Both of these categories are fraught with conflict over how they should be used. Since P21 was first created in 2013, Wikidata editors and community members have debated whether “sex or gender” should be split into separate categories and how information in this property should be privileged (Weathington and Brubaker 2023, 14). The Wikidata page for P21 does not offer much clarity. The English “Also known as” section of P21 includes such disparate concepts as “biological sex,” “gender identity,” and “gender expression,” (Wikidata n.d.a). This conflation creates confusion in scenarios when these various properties, consolidated by Wikidata, may have different values for the same individual (Centelles and Ferran-Ferrer 2024, 126). Issues with P21 were exacerbated by bots that automatically assigned “male” or “female” to identifiers based on various inferences, including by categorizing first names as either “male” or “female.” This decision quickly improved the completeness of data, but also carried the significant danger of miscategorizing individuals, queer or not, based on their name (Melis, Fioravanti, Paolini, and Metilli 2024, 204). Additionally, mass-categorizing datasets with the two categories of “male” or “female” carried with it the assumption of cis-normativity. This cis-normativity is exacerbated by the lack of gender diversity in the Wikidata and Wikipedia communities (Centelles and Ferran-Ferrer 2024, 127) (Macia, Fernandez, and Ferran-Ferrer 2025, 7). Cis-normativity persists on Wikidata, as a 2023 study found that non-binary and intersex identities are under-represented on Wikidata (Metilli and Paolini 2023, 245).

The usage of P91 (sexual orientation) has also been controversial. When it was initially introduced, it received backlash from users who did not feel that sexual orientation was a valid or important property to include in Wikidata (Weathington and Brubaker 2023, 16). P91 has persisted, but not without contestation. P91 statements require references to sources in which the individual in question “stated it themselves, unambiguously, or it has been widely agreed upon by historians after their death” (Wikidata n.d.b) This high barrier has good intentions. The goal is to prevent individuals from being “outed” and to prevent speculation about a highly personal aspect of one’s identity. At the same time, such a high standard of evidence may make it more difficult to indicate an individual’s queer identity. As Antke A. Engel has pointed out, ambiguity is inherent to forms of queerness (Engel 2021, 3). Therefore, the need for an “unambiguous” statement of queerness is contradictory, and may introduce undue hardship in representing queerness. Additionally, the requirement for a positive statement has led to a significant imbalance in the usage of P91. Since heterosexual individuals do not have to “come out,” heterosexuality is disproportionately underrepresented in P91 statements (Weathington and Brubaker 2023, 11). As a result, heterosexuality is reaffirmed as the default, while queer sexual orientations are stigmatized.

Despite the checkered history of queer representation on Wikidata, queer communities are interested in using Wikidata as a means of improving discoverability of queer history. WikiProject LGBT, a community dedicated to better representing queerness on Wikidata, recommends users add P91 and P21 to items for LGBT people as the number one way that people can help the WikiProject (WikiProject LGBT). Wikidata has a major use case in improving the representation of queer history. As the largest online knowledge graph, it is useful both as a way to connect siloed projects to broader audiences and as a central hub consolidating linked data across many platforms (Zhao 2023, 870). One scholar has even called for Wikidata to become the single identifier consolidating all other taxonomies (van Veen 2019, 73). In order to maintain the quality of queer data, users must engage with Wikidata or risk reinforcing archival gaps. In order to do so responsibly, editors can make use of The Queer Metadata Collective’s “Best Practices for Queer Metadata.” This resource provides a useful framework for ensuring that data is created with care and sensitivity. (The Queer Metadata Collective 2024). I discuss how the framework applies to this study in greater depth in a later section.

In addition to attempts to improve queer metadata and representation on Wikimedia sites, editors have also made efforts to improve the representation of women on Wikipedia and Wikimedia. Wikipedia has a documented gender gap in the makeup of its editors and its contents (Odell, Lemus-Rojas, and Brys 2022, 41). Male-dominated professions are overrepresented in the data (Zhang and Terveen 2021, 5), and women may be subject to higher “notability” standards than men (Odell, Lemus-Rojas, and Brys 2022, 40). Efforts to fix these issues included notable events like the Art+Feminism edit-a-thon, which was the largest edit-a-thon in Wikipedia history when it occurred (Evans, Mabey, and Mandiberg 2015, 197). The Women in Religion WikiProject is a recent example of a longstanding community effort to correct Wikimedia’s gender gap, by improving representation of notable women in religious academia and history on Wikidata and Wikipedia. In order to accomplish this goal, project chair Colleen Hartung has published books to improve sourcing for women in religion and push back on gender bias (Hartung 2021, iii). The Women in Religion WikiProject has successfully improved data for over 300 Wikipedia articles (WikiProject Women in Religion).

The relationship between women and religion bears similarities to the relationship between queer people in religion. Religion has historically been used to justify and enforce patriarchal and heteronormative structures that oppress and limit the agency of both groups (Alcoff and Caputo 2011, 1-10). Because of this history, there exists a perceived incompatibility between the two (Wilcox 2006, 74) Nonetheless, many women and queer people are deeply religious, and even see in theology liberatory potentialities that can enhance their agency and dismantle oppressive structures (Althaus-Reid 2003, 1-4, 155-158). Traditionally, religious studies and queer studies have been viewed as separate fields. Queer subjects are secularized and religious subjects are unqueered (Greene-Hayes 2019, 2). In recent years, there have been attempts to bring these fields closer together and to give greater space to queer religious stories in scholarly and historical circles (Stell 2024, 243).

Given the similarities between women in religion and queer people in religion, and the reparative metadata needs of both groups, it is worth exploring whether there is potential for the representation of “Queerness in Religion” to be improved, just as the representation of “Women in Religion” has improved through the Women in Religion WikiProject.

One project intended to recover queer religious history that we can draw on is the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network (LGBTQ-RAN). LGBTQ-RAN began in 2001 and is dedicated to the preservation and study of LGBTQ religious movements. LGBTQ-RAN is an example of a queer digital humanities project. They refer to themselves as a “virtual archive” and emphasize digital methods of knowledge dissemination. LGBTQ-RAN hosts over 650 profiles of leaders in LGBTQ+ religious movements, each with a short biography of the individual in question. (LGBTQ Religious Archives Network n.d.) 84 of these profiles include oral histories conducted by LGBTQ-RAN to preserve queer religious history. The LGBTQ-RAN website also has a collections catalog. While LGBTQ-RAN does not hold any physical archives themselves, the catalog provides links to locations of archival collections relating to queer religious individuals and movements. Collections, profiles, and oral histories are tagged by faith, person, and subject, using LGBTQ-RAN’s controlled vocabulary. LGBTQ-RAN acts as a central clearinghouse for collections and oral histories related to queer religious history.

LGBTQ-RAN is not an authority control database and does not have unique identifiers for its profiles. Nonetheless, there is significant value in using LGBTQ-RAN to make Wikidata entries about queer religious individuals more comprehensive. Their profiles provide a dataset of queer religious individuals whose representation on Wikidata can be examined for completeness. Editors could draw from LGBTQ-RAN’s collections to create properties like “archives at” (P485) and “oral history at” (P9600). Linking collections on Wikidata can improve archival discoverability and description, especially for marginalized communities (Babcock et al. 2021, 103-107).

All of these actions could contribute to a practice described by Marika Cifor and K.J. Rawson as “queer information activism.” Cifor and Rawson identify the Homosaurus as an example of queer information activism as a queer-led project looking to create new and more accurate subject headings to represent queer experiences. Ultimately, the purpose of the Homosaurus is to serve the queer users in libraries or cultural heritage centers. The editorial board of Homosaurus claims that by correcting exclusion and misrepresentation in knowledge systems, we can work against the “symbolic annihilation” of marginalized groups. This type of data repair can help serve users who do not see themselves represented in traditional libraries or heritage institutions. Cifor and Rawson specifically note the potential of the Homosaurus to represent yet unrealized intersectional identities, giving the relevant example of “bisexual buddhists” (Cifor and Rawson, 2023, 2168-2185). The Homosaurus builds on research indicating that data ontologies have the potential to enable research into intersectional identities, like queerness and faith (Canning, Brown, Roger, and Martin 2022, 4) (Brown et al. 2017, 1-3)1. By improving representation of queer religious individuals on sites like Wikidata, we could engage in a similar form of queer information activism. Given the historic underrepresentation of queer religious subjects, it is important that the individuals on LGBTQ-RAN are discoverable in the data beyond a siloed network.

Methodology

In order to determine how to improve representation of queer religious individuals on Wikidata, I have gathered data about the representation of individuals included in the profiles section of LGBTQ-RAN. The appendix includes rows for each person listed in the “Profiles” section of LGBTQ-RAN. In cases where two individuals share a single profile, they have been separated. I then recorded whether or not each individual had a Wikidata page, and linked it if they did. This task, and all other data collection, was done through manual data entry. This decision was made partly to ensure the quality of data in cases where individuals are listed with different names on Wikidata than they are on LGBTQ-RAN, or when an individual has a common name. (For instance, Thomas D. Hanks on Wikidata is listed as “Tom Hanks” on LGBTQ-RAN, which could create confusion). Manual data entry, of course, creates the potential for human error, which all data points may be subject to.

Each individual with a Wikidata entry is coded for six criteria: “Religion,” (R) “Religion Alluded to,” (RA) Explicit Queer Identity,” (Q) “Queerness Alluded to,” (QA) “Reference to LGBTQ-RAN,” and “Archives At.”

“Religion” refers to the P140 “religion or worldview” statement on Wikidata. If a person’s Wikidata page has this statement, they are coded as “yes” for this category, and, if not, they are coded as “no.” “Religion alluded to” refers to any other statement on a person’s Wikidata page that may indicate Religion. “Religion alluded to” primarily includes P39 “occupation” statements, such as priest, chaplain, theologian, etc. It also includes P69 “educated at” statements with the identifier of a seminary. If an individual received a “yes” coding for religion, then they also receive a “yes” coding for “religion alluded to.”

The “Explicit Queer Identity” category codes “yes” for any instances in which an individual’s Wikidata identifier includes a P21 “sex or gender” statement with anything other than “male” or “female” and/or has a P91 “sexual orientation” statement anything other than “heterosexuality.” In addition to “yes” or “no,” this category also includes an “ally” coding. Some individuals featured on LGBTQ-RAN explicitly did not identify as queer and are included for their efforts as allies to promote queer inclusion within religious spaces. Allies have their own coding so that they may be excluded from statistical queries identifying the percentage of queer people whose Wikidata profiles represent them as such. Some of the individuals listed as “No” under the “Explicit Queer Identity” category may not meet the Wikidata criteria for inclusion of a queer P91 property. They are nonetheless coded this way because they are implicitly labeled as in some way queer through their inclusion on LGBTQ-RAN and their exclusion from the “ally” subcategory. The object of this method is to foster discussion about how queerness might be represented on Wikidata in cases of ambiguity. “Queerness alluded to” refers to any statement which implies involvement in a queer community. The most common positive expression of this within the sample is the occupation (P39) “LGBT Rights Activist” (Q19509201) but other examples could include the inclusion of a same-sex partner in a “spouse” (P26) or “unmarried partner” (P451) statement. Because this category can be satisfied with statements that do not necessarily indicate an individual’s personal queerness (e.g. “LGBT Rights Activist”), allies do not have a separate coding in this category. This category can instead serve to indicate whether an individual’s involvement in queer activism is represented on their Wikidata page.

“Reference to LGBTQ-RAN” marks whether or not an individual’s Wikidata identifier includes a reference to LGBT-RAN. There is also a “Wikipedia” coding for this category, to indicate when an identifier has a corresponding Wikipedia page which includes a reference to LGBT-RAN. This column is included to indicate the extent to which LGBTQ-RAN is utilized as a resource on Wikimedia sites and to identify pages that might benefit from the information on LGBTQ-RAN. The “Archives at” column indicates whether the Wikidata entry includes an “archives at” statement. If the individual’s Wikidata page and their LGBT-RAN profile do not include any archival listings, this section is coded as “No Archives Listed.” If their LGBT-RAN profile does include an archival repository and this is not indicated on the Wikidata page, this category is coded as “No.”

Finally, I used the open source Item Quality Evaluator to algorithmically determine the quality of each Wikidata item on a scale of one to five. This is primarily given as a user aid to help determine which identifiers are in most need of improvement. The Item Quality Evaluator is only one tool for this purpose.

Using these statistics, we can examine the extent to which the intersection of queerness and religion is represented on Wikidata and find ways to improve discoverability of archival collections related to queer religious individuals.

Results

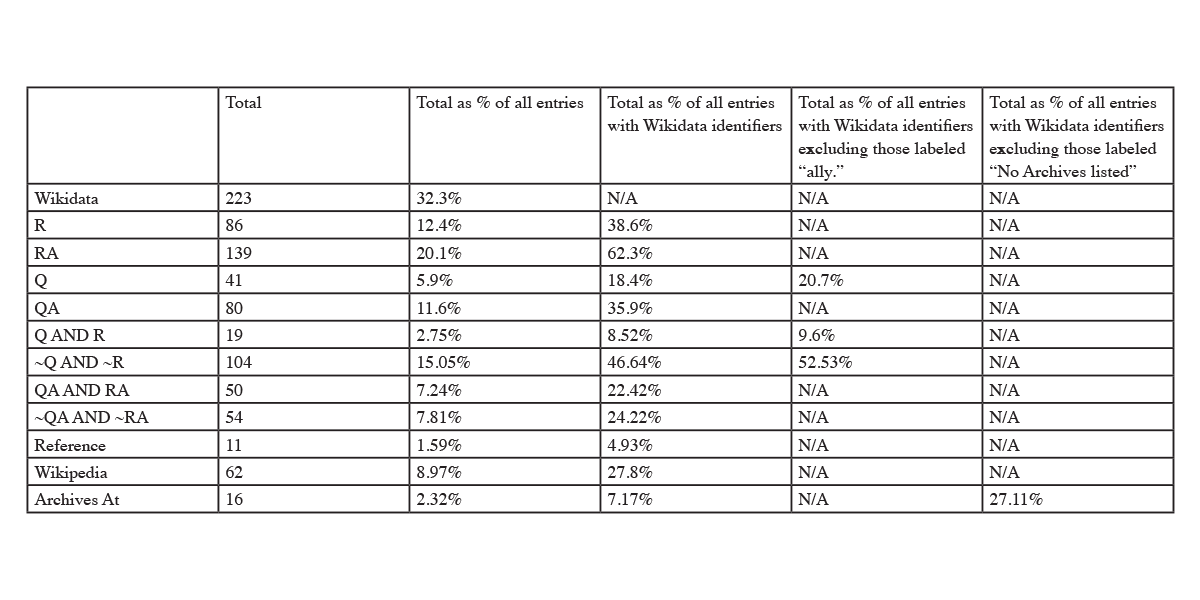

[Table 1: Queer religious representation in Wikidata. Q=Explicit Queer Identity, QA=Queerness Alluded to, R=Religion, RA=Religion Alluded to.

Roughly two-thirds (67.7%) of the profiles of LGBTQ-RAN do not have corresponding Wikidata identifiers. Religion was more likely to be indicated on Wikidata identifiers compared to queerness. This was true both in a direct comparison of P140 statements to P21 and P91 statements, and in a comparison of broader indications of queerness and religion as outlined in the methodology. While 38.6% of identifiers had P140 statements, only 18.4% of non-allies had queer P21 or P91 statements. 62.3% of identifiers contained some allusion to religion, while only 35.9% of identifiers included an allusion to queerness.

The majority of identifiers did not represent the intersection of queerness and religion. Among the sample of non-allies, using the higher standard of P140 AND (P91 OR P21) statements, only 19 identifiers, or 9.6% of the sample, included both. Using the lower standard of any allusion to religion AND any allusion to queerness, 50 identifiers, or 22.42% of the total sample, included allusions to both identities. Among the sample of non-allies, the majority of identifiers, 52.53%, had neither a P140 statement nor a queer P21 or P91 statement. 54 identifiers, or 24.22% of the total sample, included no indications of queerness or religiosity whatsoever.

Most of the profiles with associated identifiers did not have archival collections listed on Wikidata. Among those with archival collections on LGBTQ-RAN, only 27.11% had this information replicated on their Wikidata identifiers. Additionally, even though LGBTQ-RAN has conducted oral histories with 84 of the people listed on their website, none of these oral histories are represented on Wikidata, and only one person in the dataset had the property, “oral history at” (P9600) at all. There is an opportunity to use LGBTQ-RAN’s function as an archival clearinghouse to improve archival discoverability through Wikidata.

Discussion

Given the gaps in queer religious representation on Wikidata, steps should be taken to improve and create Wikidata entries for individuals represented on LGBTQ-RAN. There is already a strong basis for metadata creation for the individuals in question. One of the major problems that the “Women in Religion” WikiProject faced in improving Wikipedia representation was a lack of adequate sourcing (Hartung 2021, iii). LGBTQ-RAN has already built a robust source of biographical information for each person in the dataset, which can be used to start identifiers. Each LGBTQ-RAN biography provides ample personal information about the individual it represents, and each profile includes links to archival collections and oral history if they exist. Additionally, Wikidata does not have the stringent notability standards that Wikidata has, so all people featured on LGBTQ-RAN meet the basic requirements for an identifier.

Multiple methods might be employed to improve Wikidata entries with information from LGBTQ-RAN. One method of editing Wikidata that is becoming increasingly popular is the use of large language models (LLMs) to generate text. Bots have been used to edit Wikidata for a considerable amount of time. LLMs are uniquely useful in editing Wikidata because they can take long-form text, like LGBTQ-RAN biographies, and transform them into statements that correspond with Wikidata’s ontology. Furthermore, these models may have access to a wider variety of sources than what is represented on the LGBTQ-RAN website. Scholars have already used LLMs to improve Wikidata representation of academic conferences (Mihindukulasooriya et al. 2025, 2-4). Others have proposed that a Wikidata-like knowledge graph could be created with LLMs as a base with “minimal human interventions,” (Feng, Wu, and Meng 2024, 1). There is clearly potential for LLMs to be used on a text-based dataset like LGBTQ-RAN to transform it into standardized metadata.

Despite this potential, there are serious concerns about the usage of LLMs for such a purpose. LLMs may not be capable of reckoning with the unique sensitivity and seriousness of queer metadata on Wikipedia. As an example, I asked ChatGPT to “Create a Wikidata sexual orientation statement for Walt Whitman.” ChatGPT created a P91 statement for Walt Whitman with the value of homosexuality (Q1035954). According to current Wikidata guidelines, this would be inappropriate, as Whitman is an example of a historical figure whose sexual orientation is not a matter of settled consensus (Loving 2000, 17), and therefore is not eligible for a P91 statement. ChatGPT did not reckon with this complexity. Moreover, it provided a list of “optional qualifiers (if sourcing is desired), implying that it does not understand the strict sourcing standards uniquely required for P91 statements. (ChatGPT, May 18, 2025). The “Women in Religion” WikiProject experimented with AI usage for the creation of Wikipedia articles and found that while LLMs were in some ways effective, they were inadequate in several key areas compared to human Wikipedians (Odell et al. 2023, 17-24). Artificial intelligence is advancing faster than digital humanities research can be conducted on it, so some of these issues may have been at least partially resolved. At the moment, however, it is not clear that LLMs are capable of accurately producing the data in question.

Even if LLMs are able to provide proper sourcing and nuance in the creation of P91 statements, this still might not be a desirable outcome. The Queer Metadata Collective’s “Best Practices for Queer Metadata” instructs information professionals to “avoid using machine learning, ‘AI’, or automation for batch replacement of terms,” (The Queer Metadata Collective 2025, 22). It also explicitly states that editors should not use bots to assign gender identities to Wikidata identifiers (The Queer Metadata Collective 2025, 47). These recommendations do not entirely rule out the usage of LLMs for a project such as this, but they indicate that LLMs should be used sparingly and with care. In general, AI usage does not mesh well with the larger principles of the QMC’s document, which include constant engagement with subjects and community members and mindful, careful decision-making (The Queer Metadata Collective 2025, 19-21). These practices cannot be automatically generated.

Another option for large-scale metadata entry and repair is to host an edit-a-thon. Edit-a-thons have been a popular format for engaging community members and stakeholders in metadata projects while collaboratively improving existing metadata. Diana Marsh (along with others) has helped organize multiple edit-a-thons to encourage community members to help adapt knowledge systems to queer and indigenous representation. These efforts included multiple SNAC edit-a-thons in 2020 and 2022 (Bull, Marsh, and Wagner 2024, 268) and, more recently, the “FAIRly Obscure” events to improve anthropological Wikidata, with a focus on indigenous anthropologists. Other successful social justice-oriented edit-a-thons included the Art+Feminism edit-a-thons to improve gender representation on Wikipedia (Evans, Mabey, and Mandiberg 2015, 197) and the smaller-scale Women in Religion edit-a-thons, which have happened regularly for the past few years. These events are valuable not only for the immediate impact they have on the metadata, but for the conversations they inspire and the communities they build. The SNAC edit-a-thons helped lead to the creation of the “Editorial Guide for Indigenous Entity Descriptions in SNAC,” which is now used to shape the ways that indigenous knowledge and data is represented on SNAC (Curliss et al. 2022, 5-13) Edit-a-thons have the power to create lasting communities around data repair and interrogate the built-in assumptions of knowledge bases and their editors (Thylstrup et al. 2025, 2-5). Given the complex nature of queer representation on Wikidata, these conversations are necessary, and an edit-a-thon focused on LGBTQ-RAN data could help spark new perspectives on queer representation on Wikidata.

Key to any large-scale editing or creation of Wikidata entries using the LGBTQ-RAN dataset is a critical approach to representing queerness on Wikidata. There are 157 Wikidata identifiers for LGBTQ-RAN listed queer individuals without an explicit queer identity, 143 identifiers that have no allusions to queerness, and 468 individuals with no identifier whatsoever. It would be possible to add queer metadata for many of these individuals, but not all, given the strict requirements of the P91 property. For some individuals, it may not even be possible to include any allusion to queerness. Walt Whitman, for instance, could hardly be said to be an “LGBT Rights Activist,” and his sexual orientation is too controversial to be included in the Wikidata. Whitman has the second-highest quality score of any identifier in the dataset, a nearly perfect 4.95, and yet this comprehensive identifier contains no mention of his queerness. This absence stands in stark contrast to the scholarship on Whitman, which extensively discusses his queerness (see, for instance, Schmidgall 1997). Notably, though Whitman’s religious views are also a subject of great academic debate and ambiguity (Murray 2019), Whitman has a P140 statement. One way that queerness could be implicitly represented is by adding LGBTQ-RAN as a source, thus linking to a database that is not constrained by the restrictions of Wikidata. This solution, however, does not fix the problems of queer discoverability within the world’s largest knowledge base. If queer-created knowledge bases are the only places that such queerness can be represented, queer history might continue to be siloed away from mainstream data ontologies. To some, this might be an agreeable solution, as it would preserve the community model of queer data representation and resist attempts to limit queerness to narrow definitions. However, it may also continue the erasure of queer history and clash with the ultimate library/archival/data principles of accessibility and discoverability (Freeman 2024, 643-652). Any attempt at large-scale data reparation for individuals featured on LGBTQ-RAN would require some reconciliation of these positions and new discussions about how to represent queerness on Wikidata.

Endnotes

1 There remains skepticism about the ability for mainstream ontologies like Wikidata to properly represent intersectionality, given the limitations of representation briefly discussed earlier. Broader suggestions for how to technologically rectify these issues are beyond the scope of this project--the sources here are included merely to illustrate the potential of data ontologies in intersectional representation.