Supporting the Undergraduate Study of Theology

The Expertise Challenge

Abstract Using an autoethnographic approach, this article explores the experience of a Research and Education librarian who provides library support for undergraduate theology classes at a Catholic college, while at the same time lacking subject expertise and experience in the fields of theological and religious studies. Through the author’s own experiences and existing literature, the article highlights challenges that can be faced by a librarian in such a position. It then examines solutions, pointing to ways that librarians, without specific theological expertise, can make use of their own training and education to build their subject knowledge and better assist students and faculty.

Introduction

My journey into theological librarianship started shortly after my arrival at Providence College (PC) when I received my first student question about where they could find a Bible. This question came up with regularity, and the stock answers available to those of us in the library were less than satisfying. For example, we would ask: “What kind of Bible do you want?” Usually, the student did not know, and we, as librarians, lacked the expertise to guide them. We could suggest: “You can look for them in the BS section of our research collection on this floor or our main stacks on the next floor.” While this guided them to the general physical location of our Bibles, it did little more. Our ability to provide significant reference, instruction, or collection development was similarly limited, and students often faced important assignments and research projects with little library support in this foundational subject area.

Our experience at PC, a largely undergraduate Catholic, Dominican liberal arts college, is likely repeated at many other similar institutions that lack librarians with expertise in theology or religious studies. In a survey of librarians at undergraduate institutions, almost half, 49%, said they served as theology liaisons without any particular interest or expertise in the field (Butler 2015, 37). As a result, many libraries are unable to provide the level of support necessary for student success in this area. This realization led me to the following inquiry: how does an academic librarian lacking expertise in theology provide library support at an undergraduate institution where theology is integrated into many aspects of the curriculum?

As the Library’s Head of Research and Education at a Catholic institution, I have a responsibility to address the problem in the context of the library’s functions and capacity. Lacking formal training or expertise in the field, I have sought to use my relevant experiences as well as the opportunities available to me. These include, but are not limited to, extensive experience with teaching and mentoring undergraduates, previous work in the highly interdisciplinary field of environmental studies, and a theology-focused library project with exceptional assistance from one of the library’s student workers. With these tools, I have developed practical skills and knowledge that can be leveraged to meet students’ needs.

Method

This article is essentially the story of one individual’s experience in the context of a broader set of issues. As such, I have approached the telling and analysis of my experiences from the perspective of autoethnography. Institutional ethnography has become an important tool for understanding the internal working of organizations and their relationships with others, be they customers, patients, or library patrons. It provides the library community with an important tool for understanding ourselves and the interactions between libraries and important patron populations such as students (see, e.g., Dalmer, Stooke, and McKenzie 2017). By examining our own and these groups’ perspectives and lived experiences, libraries can provide better patron service and smoother internal operations.

It would be useful at this point to say a little more about ethnography as a method. While it has been increasingly used as a tool for studying and managing libraries, not all librarians are necessarily familiar with it. Ethnography should be systematic. It is not the collecting of random stories and experiences. Ethnography focuses on the emic or internal perspective of its research subjects. It seeks to understand the perspective and experience of the group being studied and uses techniques such as participant observation to permit the researcher to get closer to the point of view of their subjects (Bernand 2011). Qualitative ethnographic research is not necessarily easier or less “scientific” than the quantitative research and data generally used for assessment in the library world. Carefully collecting narrative descriptions from respondents is very different from survey research and can provide an important complement to quantitative studies.

An offshoot of ethnography is autoethnography, where the researcher becomes an important object of study. This is a more reflexive approach that allows for the exploration of one’s own personal experiences. Autoethnography developed as a research approach because of concerns about the way in which the personal experience and perspectives of an ethnographic researcher might affect their research. An autoethnographic approach makes these experiences and perspectives explicit as the researcher themselves becomes part of the subject of study (Adams, Jones, and Ellis 2014).

Guzik (2013) argues that an autoethnographic approach can be a valuable tool for library and information science research. As librarians doing research on librarianship, we are inevitably part of our subject of research. An autoethnographic approach allows for a more explicit awareness of this. In the case of this study, I am both the researcher and a research subject seeking to understand why and how I can better provide theological library services at a predominantly undergraduate Catholic college. As such, it makes sense to use a methodological approach that explicitly positions me as both subject and researcher in this process.

Another virtue of an autoethnographic approach is that it allows for the addressing of some anthropologists’ concerns regarding the quality of library ethnographic work. Lanclos and Asher (2016) have formal ethnographic training and experience as well as having undertaken ethnographic research at the libraries of their home institutions. Writing in both a critical and sympathetic manner, they describe most library ethnography as “ethnographish.” While using ethnographic tools such as participant observation, most library ethnography projects are short-term and narrowly focused on specific management or assessment objectives. Autoethnography, or at least this application of it, provides an element of correction in two ways. One, it is largely longitudinal in nature, as the processes described in this study are informed by several years of experience and observation. Two, it did not begin with any predetermined research question or goal in mind. I began with what I thought was a simple task, making it easier for students to find the Bible(s) they needed for their academic work. Over time, it has expanded to its present focus, the question of how a librarian without theological expertise can best provide theological library services to undergraduates at a Catholic institution.

CONTEXTUAL REVIEW

The Role of Theology Librarianship at Undergraduate Institutions

In the United States, there are 260 Catholic institutions of higher education with a combined total of 870,00 students (Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities 2020). In one form or another, theology is commonly integrated into many of these schools’ general education programs. As a result, Butler’s (2015) work on librarians at undergraduate institutions doing some form of theological librarianship is exceptionally relevant. There were only seven respondents from Catholic schools in Butler’s survey, making this subsample far too small to generalize from. However, at least three of these librarians meet her criteria for being unlikely to see themselves as “theological librarians.”1 Extrapolating from this observation, it seems probable that a not insignificant percentage of those 870,000 students are undergraduates at institutions with some sort of theology requirement but with no such expertise in the library.

My colleagues and I at PC’s Phillips Memorial Library are in a situation similar to the librarians in Butler’s survey. As a Catholic institution, PC integrates the study of theology into many aspects of its undergraduate curriculum. The school’s Core Curriculum requires all undergraduates take at least two theology courses (Providence College Faculty Senate 2010). In the 2019-20 academic year, 103 theology courses were taught by the Theology Department, in large part to meet this Core Curriculum requirement. Theology is also an important part of PC’s distinctive Development of Western Civilization (DWC) program. This consists of three semesters of seminars studying significant texts from antiquity to the modern period and a fourth, team-taught semester-long colloquium focused on a specific contemporary issue. The seminars, colloquiums, and teaching teams are all interdisciplinary, with theology as an important part of the mix of disciplines.2 Every undergraduate at PC thus takes at least six courses where theology is the central, or a significant, component of the course content, and the library has a clear responsibility to assist students with such work.

However, support for specific academic programs or courses is not the only way that demand for theological resources manifests itself at Catholic undergraduate institutions. Undergraduate curriculums exist in the context of a school’s overall goals and missions. This is particularly true of Catholic institutions such as Providence College which exist in a broader cultural and organizational context. There is a long-running conversation about the meaning and direction of “Catholic higher education” and the appropriate nature of a Catholic university or college’s “core curriculum.” The discussion occurs in academic works (see, e.g., Roche 2015), the work of Catholic-affiliated organizations (see, e.g. Project on General Education and Mission 2009), official church pronouncements, most notably Pope John Paul II’s 1990 Ex Corde Ecclesiae, and even in Providence College’s student newspaper, The Cowl (Kulesza 2020).

Potentially, libraries have an important enabling role to play in these conversations. Morey and Piderit (2006) identify the role of “knowledge experts” in the process of sustaining culture. They also note the historical role that members of religious orders have played as knowledge experts at Catholic colleges and universities. As such individuals become fewer in number, new knowledge experts will have to come from the lay administration, faculty, and staff whose religious education and experience is generally less than those they are replacing. While academic libraries and librarians do not directly function as knowledge experts, they can, in a more indirect manner, provide the information services and resources necessary for the emergence of such new knowledge experts.

My institution provides a clear example of the changing background of faculty members. In 1939, 54 of 68 “officers of instruction” were members of the Dominican Order (Providence College 1939). Thirty years later, in 1969, 72 of the 195 “faculty personnel” were Dominicans (Providence College 1969). Most recently in 2020, 15 of the 274 “full-time” faculty were members of the order (Providence College 2020). This represents a decline from 79% of the faculty in 1939 to 5% in 2020, highlighting the importance of having some degree of theological expertise in the library to enable the emergence of alternative knowledge experts.

The importance of knowledge experts could be seen when PC recently completed a major strategic planning exercise, PC200, which took place in the context of this conversation on Catholic higher education. The overall vision and several of the important goals that are articulated by this strategic plan clearly reference religious values …

“Vision – Providence College will be a nationally recognized Catholic, residential, undergraduate-focused, higher-education institution.

Goal 1 - A Distinctive Educational Experience … in the 800-year-old Dominican tradition of critical inquiry

Goal 2 - A Model of Love, Inclusivity, and Equity in a Diverse Community … inspired by Catholic teaching and St. Dominic’s wide embrace of all people,” (Providence College 2018)

Consequently, the Library provided research support for this planning process (Future of Higher Education Research Team 2022). This required an effort to provide the most useful information and resources when there was, at times, a lack of the theological subject expertise necessary to address the religious and spiritual values expressed in the strategic plan.

Professional (Re)development

Questions of retraining and developing knowledge in new fields have always been of central importance to me. And they are equally relevant to many other academic librarians at predominantly undergraduate institutions where there are few subject specialists. There is literature on significant mid-career changes by librarians, such as Fontenot’s (2008) description of his move from being a law librarian to one who does more general reference and instruction. However, this literature seems to be more limited when it comes to the more subtle, but no less important, aspect of ongoing professional development - providing reference, instruction, and collection management support for academic disciplines with which we lack familiarity.3

When considering the process of professional (re)development, it is important to recognize the agency of individual librarians and the context created by institutions, libraries, academic departments, colleges, etc. As one example of the role of the individual, Fontenot (2008) provides a very nice personal description of his experience shifting from law librarianship to a reference and instruction position at a large university. Interestingly, Fontenot emphasizes the importance of humility (27), a theme which will be developed further below. It’s critical to acknowledge the areas where we lack knowledge and experience and be willing to seek out those with the necessary expertise to assist us.

It is also critical that we, as librarians, regard ourselves as learners. To enhance communication between ourselves and disciplinary academics and facilitate a process of learning by doing, we can use the development of library instruction material as the context for gaining disciplinary knowledge and developing relationships. This practice allows for “active experimentation” and the continued refinement of instructional materials. (Luca 2019, 82).

The support of institutions as well as individual initiative is also vital for professional (re)development. In a statistical analysis of librarians and their career moves in South Korea, support from managers and the overall institution were found to have the strongest relationship with librarians pursuing various forms of career development (Noh 2005).

Smith (2008) looks at how academic libraries can adapt to the “emerging discipline” of game studies. In a number of conceptual ways, enhancing one’s knowledge of and experience with an existing discipline is similar to the manner in which one would approach providing services for a new one. In both cases, librarians must develop subject expertise on the fly, making use of the skills, experiences, and resources available to them. Smith advocates that all the departments of a library be involved in developing new expertise and services. Both reference and instruction and collection development play important roles in generating understanding of an unfamiliar discipline and can reinforce one another’s work. I have been fortunate in the support I have received from other departments of our library.

CHALLENGES

Providing library support for undergraduate theology research and teaching without subject expertise presents numerous challenges, even more so at an institution such as PC where the discipline is such an important part of the curriculum and culture. At PC, as at many undergraduate institutions, librarians are generally hired for their flexibility and ability to fill multiple roles as well as their experience working with undergraduates, rather than their disciplinary expertise and experience.

I have spent time talking to my library colleagues at PC and elsewhere about what they see as major obstacles to providing library support to undergraduate theology study. In these conversations, two major themes have emerged: the first one is “benign neglect” and the second is “apprehension.” “Benign neglect” arises when one focuses on another part of one’s job or library support for the college as a whole, as opposed to any specific discipline. There is plenty of work to do in an academic library, and every librarian has particular interests that they prefer to focus upon. Using myself as an example, I am particularly interested in maps and geospatial data library work. When there are no librarians with specific expertise or interest in a topic, it is more likely to be neglected, albeit benignly. Without subject matter expertise, such as in the case of theological librarianship being examined here, it is more likely to remain out of sight and out of mind.

While “benign neglect” can occur at almost any institution and regarding almost any topic, there are specific challenges to supporting the theological education of undergraduates at a Catholic institution such as PC. This is the set of challenges which falls into the “apprehension” category. Other PC librarians and I are aware of the importance of the discipline of theology and the expertise of not only the theology faculty but also many others on campus, most obviously the members of the Dominican Order who are an important and highly visible part of the campus community. Several colleagues expressed apprehension about doing theological librarianship without sufficient expertise in such a setting. There is concern about making an embarrassing mistake, accidentally stepping on the theological version of a landmine, and lacking the basic vocabulary to communicate effectively. Ironically, the very importance of a discipline to an institution, such as theology to PC, can make it more difficult for non-subject expert librarians to feel confident in providing library support for it.

EXPERIENCES

A major virtue of autoethnography is the degree to which it allows the researcher to reflect upon themselves. During my time at PC working on this topic, I found several strategies that have been useful in the absence of subject matter expertise.

Interdisciplinary Experience

The first is my interdisciplinary experience in the field of environmental studies. This has provided me with two advantages that I have been able to capitalize on. I had some awareness of theological and religious topics to the degree they intersected with environmental studies. For example, there is a classic, and oft-debated and critiqued, environmental studies article from 1967 by the historian Lynne White which to a great degree blames Christianity for “our [current] ecological crisis.” There are also theologically informed environmental arguments such as those presented in Pope Francis’s 2015 Encyclical Letter, On Care for our Common Home, which invoked the language of “stewardship” and the historical example of St. Francis of Assisi.

The second, and perhaps more important, advantage provided by teaching and doing research on environmental studies was the opportunity to cultivate humility. Very early in my environmental studies career, I learned the full extent of what I didn’t know and came to appreciate the way my political science training did not provide expertise in the natural sciences or humanities. Due to this experience, I am exceptionally aware of the need for collaboration, identifying appropriate sources of expertise when I find myself lacking such, and communicating successfully with scholars, students, and the general public over a wide range of technical topics and concepts. All in all, I better understand the extent of my “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns,” which has been liberating and made me more effective at collaborating with those coming from disciplinary, philosophical, and life experiences different from my own.

Role of Spirituality

In his 2017 essay, Wagner makes a compelling argument that librarianship can be seen as a “spiritual practice.” He describes a method which he calls bibliothecarius Divina (sacred librarianship) (4), which he patterns after the practice of lectio divina (Robertson 2011). An important part of this process is the final, contemplatio step. In a number of ways, this is very similar to the reflexive and self-aware nature of autoethnography. Both require a consciously thoughtful approach to our lives. While neither spirituality nor the reflective nature of autoethnography are strictly necessary for the practice of librarianship, theological or otherwise, I agree with Wigner that spiritual practice in a library setting allows the opportunity to think more deeply about the nature of our work and our relationships with our colleagues and our patrons.

Three spiritual values which have been exceptionally important for me and for this project are humility, gratitude, and an understanding of how library spaces can foster spirituality. My understanding of humility has further deepened since my time in environmental studies, particularly my awareness of the subtleties and complexities of the humanities. Librarianship is the ultimate interdisciplinary field where we are continually reminded of the limitations of our own knowledge and the need for collaboration with others.

Gratitude is an additional and important dimension of spirituality (Steindl-Rast and Grun 2012), and there is a specific way that it is relevant to this project. During the 1990s, I conducted dissertation research in northern Tanzania on the relationship between cattle-keeping pastoralist communities and large-scale conservation and development projects. The then Diocese of Arusha (now an Archdiocese) was heavily involved in development work in the area and had a specific program focused on assisting pastoral communities with issues of land rights. The experience of doing research on the Church’s efforts, supporting their work, and being supported by them had a very profound impact upon me. I have enduring gratitude to this community for the intellectual and material support it provided to me during the early phases of this research. This includes specific gratitude to the nuns of the Diocese’s guest house who aided me during a bout of malaria. Now, a quarter of century later, I find myself working at a Catholic institution of higher education where I have an opportunity through my library service to repay what was freely given to me.

Finally, Grenert (2020) focuses on “theological libraries as spaces for spiritual formation,” but I would argue that all libraries can serve this purpose. In a small way, the “Bibles at the ResearcHub” 4 collection described below can be seen as a small “sacred space” that breaks down the vision of an academic library as a purely intellectual project with little or no connection to other parts of our lives. This fits with PC’s strategic goal of “integrating interdisciplinary experience with personal, professional, and spiritual development” and with an interest in the academic library world generally, and our library in particular, of supporting the whole student.

Undergraduate Teaching Experience

While I lack theological expertise, I have significant experience teaching undergraduates and working with them on research projects. This provides a complementary expertise to the faculty’s disciplinary expertise. Librarians with undergraduate teaching experience tend to be good at assisting students early on in their research projects, a phase that has been identified as the most difficult for many students, particularly early in their college careers (see, e.g., Head 2013). This benefits students at PC and provides me with an opportunity to enhance my knowledge of theology when directly or indirectly collaborating with theology and other faculty. An example of indirect collaboration is the creation of online research guides either at the disciplinary level or, when necessary, for specific courses.5 I have found that creating material for students is far more educational for me than just studying a topic on my own.

I have also worked with several theology and DWC faculty by providing library instruction and support for their classes. This experience has provided access to their syllabi and research prompts, creating an opportunity to discuss learning outcomes. These insights allow a better sense of what information resources students need for their research projects. This opportunity has been particularly important because, as a data librarian and interdisciplinary social scientist, my previous collaborations have been with natural scientists and other social scientists. A major challenge has been the nature of “data” and “primary sources” required by undergraduates for their theology research projects. One discovery has been that the quality of collaborations and communications with faculty is often more important than the quantity. I have found myself learning more during a sustained interaction with one specific faculty member than through short emails to a dozen or more faculty.

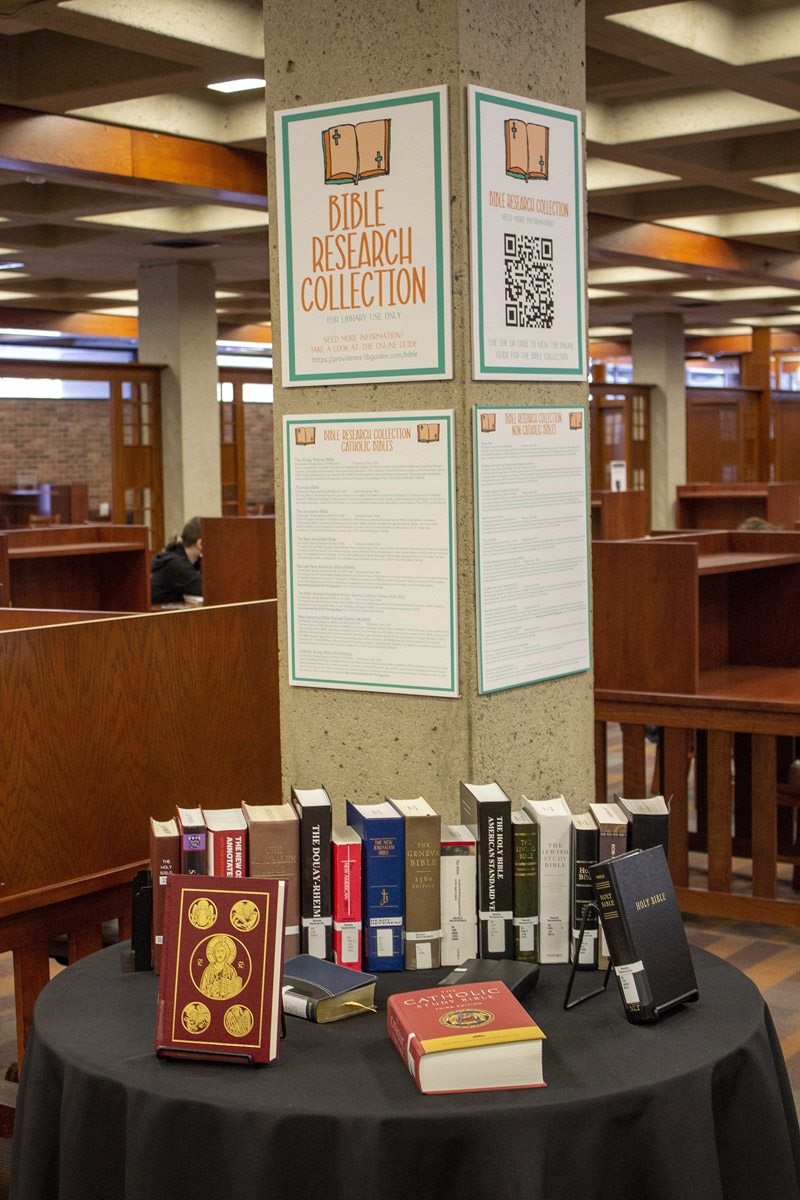

Relevant Projects

One of the most important things I did to increase my subject knowledge and expertise was to find a theology-focused library project that would be useful to students and educational to me. A major initial inspiration for my interest in theology was the “where’s a Bible?” question. So, I embarked on a mission to create a user-friendly tool for students, the “Bibles at the ResearcHub” collection. This theology-focused library project has been useful to students, enhanced my awareness of the library’s ability to support the undergraduate study of theology, and has been educational for me. In an abstract way, I knew there were many versions of the Bible, but I really did not know much more. Working on this project broadened my knowledge. It has provided me with new opportunities for intra-library collaboration, working with our Department of Collections Services, and continued collaboration with theology faculty in order to deepen my understanding of theological librarianship.

The creation of this collection was not always without strains. Among the twenty Bibles, I had selected, ten Catholic and ten non-Catholic, were the Living Bible and the New Living Translation. One theology professor was critical of the inclusion of such paraphrase and “thought-for-thought” translations in the display. As a librarian and social scientist, I felt that while they might not be well suited for serious biblical studies work, they are important as socio-cultural artifacts. A compromise was reached, and this warning, “NOT recommended as a source for theological research or study of the Bible,” was added to these items’ descriptions. Similarly, “Recommended by the PC Theology Dept” was added to the descriptions of several Bibles. The process of reaching this compromise was itself a useful window into the discipline of theology.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, the PC library like others was physically closed, and the whole display was made available online.6 Links to full-text online versions of the Bibles in the collection were provided whenever possible. Now that the library is open again, the physical display has returned and has been publicized on social media by our Media Support and Outreach Coordinator, and the physical collection has been supplemented by the online one developed during the pandemic. Students now have multiple opportunities to discover and study these texts.

The PC library has memberships in several relevant organizations that I found helpful during my exploration of theological librarianship, such as the Catholic Library Association, but we have not fully realized the benefits of these memberships for the work described here. An unexpected benefit of the COVID pandemic is that many organizations are hosting online meetings, without the requirement to travel. So, such organizations and their online meetings and events have been another resource for me to draw upon.

Lastly, I have sought to broaden this discussion to include all the librarians at PC. In fact, we have had several preliminary conversations about “What it means to be an academic library at a Catholic and Dominican institution.” It is very important to be intentional and formal about such a process, as informal conversations and initiatives run the danger of falling victim to the “benign neglect” problem noted above. A joint meeting of our Research and Education and Collections Services Groups had been scheduled for April 2020 to discuss this very topic. Our initial, tentative institutional efforts were overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on academia. However, it is again something that we are now focusing upon.

Things To Do

There are also some possible strategies we have not fully explored. Butler (2015) suggests that organizations such as Atla could organize meetings, training sessions, and online resources for librarians such as myself (39-40). While the pandemic did offer the unexpected benefit of allowing us to engage more with groups such as this, we at PC do need to investigate further the opportunities available to us through Atla and other relevant organizations. Another related, important approach is to devote more effort to networking and researching what other institutions similar to PC are doing.

A second major strategy would be a greater prioritization of Collections Services as part of the library’s work to support the undergraduate study of theology. While there has been some success in cultivating relationships with individual faculty, a more systematic approach to managing our theology collection requires a stronger programmatic relationship between the library and the Theology Department and DWC program here at PC. Small steps have been taken in this area with the library promoting open textbooks and other open educational resources to the DWC program and a DWC Textbook Program that makes all the DWC readings available to students as reserve material.

DISCUSSION

There are a couple of general takeaways from the PC experience. First, despite PC’s unique institutional characteristics, I suspect that I am far from alone in this situation. Butler’s 2015 survey demonstrated the degree to which librarians supporting the study of theology at undergraduate institutions often lack theological expertise. My own anecdotal experience and conversations with library colleagues at PC and elsewhere has further convinced me of the soundness of her findings and the resulting impact this has on undergraduates at colleges such as PC with significant theological content in the curriculum.

My second takeaway is more optimistic. My experience does provide a partial roadmap for others in my position. While I lack theological expertise, I was able to use my expertise in other areas - undergraduate teaching and research mentoring, and environmental studies - to complement the disciplinary expertise of those theology faculty teaching undergraduates. I would also like to stress the importance of a project or something similar to keep one focused. Here at PC, that project was the “Bibles at the ResearcHub” collection that was created in collaboration with Collections Services and a student worker. This was a good example of involving undergraduate student workers in significant library projects which further supports our educational mission.

As a possible future research project, it would be useful to survey the “demand” for theological librarianship expertise at undergraduate-focused institutions. This would complement Butler’s work which looked at the supply side of theological librarianship at undergraduate institutions. This could be done through a survey of course catalogs (Glazner et al 2004) and/or a survey of librarians at such institutions. Much qualitative work has been done on core curriculum/general education at Catholic colleges and universities (see, e.g., Brown 2020), but there appears to have been much less quantitative survey work in this area.

Conclusion

Finally, I will close with a brief description of the emotional high point of my work in this area. One pre-pandemic evening when I was working a shift at our ResearcHub, one of the theology faculty with whom I had collaborated, a Dominican Father, arrived with his Development of Western Civilization class and his co-teacher, a local Rabbi. They wanted their students to compare the style and content of different Bibles. Because of the creation of the “Bibles at the ResearcHub” collection, the knowledge I gained creating that collection, and the assistance of one of our circulation staff, we were quickly able to fill a book cart with Bibles and wheel it into the library classroom where the class was meeting. As I left the room, the Bibles were being energetically passed around, and I was filled with a feeling of great satisfaction that we were able to quickly provide the texts needed by faculty and students, instead of just pointing toward the BS section of the collection. Now that we have returned to in-person teaching, I am looking forward to similar experiences in the future.

Works Cited

Adams, Tony E., Stacy Holman Jones, and Carolyn Ellis. 2014. Autoethnography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/providence/reader.action.

Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. 2020. “Five Facts About Catholic Higher Ed.” https://www.accunet.org/Portals/70/Images/Publications-Graphics-Other-Images/FiveFactsAboutCatholicHigherEd.jpg.

Bernand, H. Russell. 2011. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 5th ed. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Brown, Gabriella De Santis. 2020. “Mission Effectiveness and Institutional Environment: Influence of Catholic Mission on Undergraduate Core Curriculum Programs.” PhD diss., Fordham University.

Butler, Rebecca. 2014. Expertise and Service Survey Results. Library Faculty Publications. https://scholar.valpo.edu/ccls_fac_pub/19.

Butler, Rebecca. 2015. “Expertise and Service: A Call to Action.” Theological Librarianship 8, no. 1: 30–41. https://doi-org.providence.idm.oclc.org/10.31046/tl.v8i1.352.

Dalmer, Nicole K., Rox Stooke, and Pam McKenzie. 2017. “Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for Librarianship.” Library and Information Research 41, no. 125: 45-60. https://lirgjournal.org.uk/index.php/lir/article/download/747/765.

Fontenot, Michael J. 2008. “The Ambidextrous Librarian, or ‘You Can Teach a Middle-Aged Dog Some New Tricks.’” Reference & User Services Quarterly 48, issue 1: 26-28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20864987.

Francis. 2015. Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home. Encyclical Letter. http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html.

Future of Higher Education Research Team. 2017. “Future of Higher Education.” Providence College. http://library.providence.edu/fhertr/.

Glazner, Perry L., Todd C. Ream, Pedro Villarreal, and Edith Davis. 2004. “The Teaching of Ethics in Christian Higher Education: An Examination of General Education Requirements.” The Journal of General Education 53, no. 3-4, 184-200. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27797991.

Grenert, Briana. 2020. “Out of the Cloister: Theological Libraries as Spaces for Spiritual Formation.” Theological Librarianship 13, no. 2: https://serials.atla.com/theolib/article/download/1937/2214.

Guzik, Elysai. 2013. “Representing Ourselves in Information Science Research: A Methodological Essay on Autoethnography.” Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science 37, no. 4: 267-283. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/536795/pdf.

Head, Alison. 2013. How Freshmen Conduct Course Research Once They Enter College. Project Information Literacy Research Report. https://projectinfolit.org/pil-public-v1/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/pil_2013_freshmenstudy_fullreportv2.pdf.

John Paul II. 1990. Ex Corde Ecclesiae: Apostolic Constitution of Catholic Universities. Encyclical Letter. http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_constitutions/documents/hf_jp-ii_apc_15081990_ex-corde-ecclesiae.html.

Kulesza, Joseph. 2020. “Just How Catholic are Catholic Schools? Taking Pride in the Strength of PC’s Catholic Identity.” The Cowl, October 29, 2020.

Lanclos, Donna, and Andrew D. Asher. 2016, “’Ethnographish’: The State of the Ethnography in Libraries.” Weave: Journal of Library User Experience 1, no. 5. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/idx/w/weave/12535642.0001.503/--ethnographish-the-state-of-the-ethnography-in-libraries.

Luca, Edward Joseph. 2019. “Reflections on an Embedded Librarianship Approach: The Challenge of Developing Disciplinary Expertise in a New subject Area.” Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 68, no. 1: 78-85. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/20060/LUCA_E_JALIA_22_01_19_FINAL.pdf.

Morey, Melanie M., and John J. Piderit. 2006. Catholic Higher Education: A Culture in Crisis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Noh, Younghee.2011. “A Study on the Conceptualization of Librarians’ Career Movement and Identification of Antecedents.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 43, no. 4 (2011): 213-223. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0961000611418814.

Project on General Education & Mission. 2009. “A United Endeavor: Promising Practices in General Education at Catholic Colleges and Universities.” https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3924406/AUnitedEndeavor.pdf.

Providence College 1939. Bulletin of Providence College 1939-1940. Providence, Rhode Island.

Providence College 1969. Bulletin of Providence College 1969-1970. Providence, Rhode Island.

Providence College. 2018. “PC200: Embarking on Our Second Century, Building from Strength, Enhancing Our Distinction.” https://strategic-plan.providence.edu/pc200-full/.

Providence College. 2020. “Fact Book 2020-2021.” https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.providence.edu/dist/a/14/files/2021/11/fact-book-external-2020-21.pdf.

Providence College Faculty Senate. 2010. “Changes to the Core Curriculum.” https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.providence.edu/dist/1/6/files/2018/02/faculty-senate-core-legislation-18wepr6.pdf.

Robertson, Duncan. 2011. Lectio Divina: The Medieval Experience of Reading. Cistercian Studies v. 238. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4735419.

Roche, Mark W. 2015. “Principles and Strategies for Reforming the Core Curriculum at a Catholic College or University.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 34, no. 1 (2015): 59-75. https://mroche.nd.edu/assets/287521/roche_catholic_core_curriculum_jche_341_2015_.pdf.

Smith, Brena. 2008. “Twenty-first Century Game Studies in the Academy: Libraries and an Emerging Discipline.” Reference Services Review 36, no. 2: 205-220. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/00907320810873066/full/html.

Steindl-Rast, David and Grün Anselm. 2016. Faith Beyond Belief: Spirituality for Our Times: A Conversation. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/providence/detail.action?docID=4659044#.

White, Lynn. 1967. “The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis.” Science 155, no 3767: 1203-1207. https://jstor.org/stable/1720120.

Wigner, Dann. 2017. “Librarianship as a Spiritual Practice.” Theological Librarianship 10, no. 1: 2-4. https://doi.org/10.31046/tl.v10i1.455.

Endnotes

1 This extremely brief analysis was doing by examining Butler’s (2014) survey results.

2 For a more complete view of the DWC program, go to https://western-civilization.providence.edu/.

3 See Luca (2019) for an exception to this general trend.

6 The latest version of the Bible Guide can be found here, https://providence.libguides.com/bible .