When DEIA meets faith in heightened tensions

DEIA initiatives at Catholic-serving institutions

abstract Copley Library at the University of San Diego launched the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Committee in August 2020. The committee was developed in an effort to identify and work through the DEIA-related challenges affecting our country and our local community. Three librarians from the committee endeavored to explore what USD is currently doing as well as how libraries at Catholic-Serving Institutions are providing resources and services in regard to DEIA. Our approach was to survey USD faculty, staff, and administrators who participate or engage in DEIA efforts. The external survey was intended for librarians who work at Catholic-serving Institutions, but not necessarily involved in any kind of DEIA initiative on their campus.

Introduction

In August 2020, Copley Library at the University of San Diego (USD) formally created the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Committee in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, #MeToo, and the repeated, violent attacks on people from marginalized groups on our campus and in the larger society. This standing, action-oriented committee’s founding membership includes a racially and ethnically diverse group of six library faculty and staff members representing a host of library and information services (LIS) areas - technical services, reference, instruction, archives, and access services. Copley Library’s commitment to DEIA is articulated in three spaces: the 2021 - 2024 Strategic Plan, the Diversity and Inclusion Resources LibGuide, and the DEIA Committee charge. The statements reveal a layered mission-to-action orientation for Copley’s DEIA efforts. Our definition of DEIA is guided by the institution’s Center for Inclusion and Diversity, which defines diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice, as presented in the following table. Accessibility is not formally addressed beyond adherence statements for technology purposes and signals a key area of future institutional growth.

|

Resource |

Statement (emphasis ours) |

|

Center for Inclusion and Diversity |

Diversity refers to difference, understood as an historically and socially constructed set of value assumptions about what/who matters that figures essentially in power dynamics from the local to the global. Inclusion refers to how institutional practices, policies, and habits transform to include diverse people and perspectives, especially those from underrepresented and underserved groups. Equity is the process of modifying practices that have intentionally or unintentionally disadvantaged a particular group. Social Justice operates centrally in Catholic social teaching. Social justice entails identifying and contesting processes in which power and privilege utilize diversity for inequitable outcomes along intersecting lines—race, class, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ability, and more—that inhibit democratic empowerment, civil and human rights. |

|

2021 - 2024 Strategic Plan |

The core values of the University of San Diego guide Copley Library, an innovative leader in information access and application. We develop digital and print collections that support research and teaching. We value scholarship and meaningful improvement through assessment, community engagement, diversity, social justice, and sustainability efforts. In a welcoming and inclusive environment, we provide outstanding service to our users. |

|

Diversity and Inclusion Resources |

Copley Library’s mission is to serve all students, staff, and faculty regardless of race, color, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, ability, gender identity, or gender expression. |

|

DEIA Committee |

The Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Committee will assist the library in creating an equitable and diverse environment by working with library employees to explore and develop the collection, programming, professional development, services, and additional content for the university community. Table 1: DEIA-related definitions from USD’s Center for Inclusion and Diversity and DEIA priorities expressed in Copley Library’s strategic plan, mission statement, and DEIA Committee charge. |

The committee’s first post-formation tasks involved developing a charge to articulate the committee’s mission and scope and an agenda of short- and long-term goals, and curating the LibGuide and relevant resources. The committee initiated collaborative partnerships with other Copley committees (e.g., Retreat and Professional Development Committee) and USD partners to invite experts and practitioners for presentations about Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), undocumented students, Safe Zone training, and LGBTQIA+ support on campus. The committee also partnered with the Social Media team to develop an outreach plan.

As scholars and practitioners, the committee developed a research branch with the three tenure-line faculty members. Our research aims to: (1) support committee and library DEIA actions with theoretical and evidence-based research and (2) produce and disseminate our work with the scholarly community through presentations, publications, and grey literature. This paper expresses the development and results of our exploratory research project of the DEIA mindset and actions of Catholic-serving colleges and universities and their libraries. The research project developed from committee member discussions regarding what other libraries at Catholic-serving higher education institutions were doing to address the heightened racial reckoning and protests American society experienced after the murders of George Floyd, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and other marginalized people by police and white supremacists. Additionally, this research explores how Catholic identity impacts how institutions, faculty, and staff address DEIA on their campuses. This paper is a report of the findings of our survey- and literature-based research. While it may provide a stepping stone for explorations into the complicated relationship between Catholic identity and DEIA principles, this paper leaves that work to future projects.

Literature Review

Catholic Identity

Catholic identity is an essential component of the Catholic education tradition. Recognizable visual representations include faculty clergy like priests and nuns in their traditional robes or habits, and buildings such as ornate churches or chapels on campus. However, as faculty clergy decrease and the layperson or non-Catholic faculty increase, the once frequent visual markers of Catholic identity become less visible (Heft and Pestello 1999; Heft, Katsuyama, and Pestello 2001). In the Ex corde Ecclesiae, Pope John Paul II (1990) directed Catholic universities and colleges to publicly declare their Catholic identity “either in a mission statement or in some other appropriate public document” (as cited in Gambescia and Paolucci 2011, 4). Gambescia and Paolucci (2011) note Pope John Paul II’s directive for Catholic higher education administrators to “freely and consistently express their Catholic identity…[and] ensure that faculty, staff, and administrators, at the time of their appointment, are informed of the university’s Catholic identity and its implications, and, most importantly, about their responsibility to promote, or at least to respect, that identity” (Gambescia and Paolucci 2011, 4). University administrators applied this edict to support Catholic identity to faculty and staff hiring processes. Similarly, Pope Benedict XVI (as cited in O’Connell 2012) stated,

It is from its Catholic identity that the school derives its original characteristics and its “structure” as a genuine instrument of the Church, a place of real and specific pastoral ministry. The Catholic school participates in the evangelizing mission of the Church and is the privileged environment in which Christian education is carried out…The ecclesial nature of the Catholic school, therefore, is written in the very heart of its identity as a teaching institution. It is a true and proper ecclesial entity by reason of its education.

Since the 1990s, multiple higher education scholars have researched how Catholic identity is represented, implemented, and assessed in Catholic colleges and universities. Janosik’s 1999 study established a framework to identify Catholic identity content using three pillars and eighteen variables. The Estanek, James, and Norton study (2006) establishes five categories of Catholic identity: (1) statements of Catholic identity; (2) connection to the sponsoring Catholic religious order; (3) academic programs and institutional activities; (4) community; and (5) diversity. Boylan’s 2015 study examines how students perceive Catholic identity and its impact on their interactions with the institution’s mission and values. Schuttloffel’s 2012 work reviews recent practitioner and collaborative examinations of how American Catholic educators’ insular perceptions of Catholic identity may inhibit progress and development. Other scholars note Catholic higher education’s efforts to create a “complex ideal that affects many dimensions of students’ learning and development and that requires not only the collaboration of administration, faculty, and staff but also the response of the students” (Estanek et al. 2006, 205; Schuttloffel 2012).

USD identifies in its mission and vision statements as “an engaged, contemporary [Roman] Catholic university” (University of San Diego 2021). USD’s Catholic identity is explicitly declared as:

The University of San Diego expresses its Catholic identity by witnessing and probing the Christian message as proclaimed by the Roman Catholic Church. The university promotes the intellectual exploration of religious faith, recruits persons and develops programs supporting the university’s mission, and cultivates an active faith community. It is committed to the dignity and fullest development of the whole person. The Catholic tradition of the university provides the foundation upon which the core values listed below support the mission. (University of San Diego 2021)

Few specific expressions or perceptions of USD’s Catholic identity exist in the recent scholarly literature. In Davis et al. (2015), Monica Stufft describes it as:

Similarly to the Catholic University of America, the University of San Diego [USD] is also an independent Catholic university in that it is not directly connected to a particular diocese or order, such as the Jesuits. USD understands itself as a Roman Catholic institution, but what that means in practice is much debated. Some would say that USD privileges academic freedom over its Catholic identity while others would assert the opposite. My experiences at USD have made me think a lot about how institutional identity is a negotiation and a process. One of the things that has been running through our comments is differing understandings of Catholicism and, as a result, how our institutions carry out their affiliations to the Catholic Church in various ways (278).

Later when discussing drag performances on campus, Stufft highlights difficulties navigating the expectation to support USD’s mission and Catholic identity, “while also fulfilling my responsibility to my students and to my field” (Davis et al. 2015 281). Stufft’s statement echoes challenges faced by stakeholders in other Catholic scholarly literature (e.g., Alba 2006; Kabadi 2018) and the results of this study.

DEIA in Catholic colleges and universities

Systemic racism and institutionalized oppression are no strangers to higher education, particularly at predominantly White institutions (PWI). From the early rules of gatekeeping and educational access, denials to those not considered White males - often of a certain economic class - to today’s biased standardized assessments and embedded school-to-prison pipeline designed to maintain the white supremacist status quo, the education system mirrors and perpetuates social norms and processes.

A consistent tension exists between the disenfranchised or marginalized and the dominant or oppressive and those who benefit by proximity or silence. During slavery, many enslaved would secretly pursue education despite unjust laws and the threat of cruel punishment or death. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s saw Black people fighting for the same rights enjoyed by White men to live and participate fully and freely in society without threat. Today, state-sanctioned law enforcement and self-appointed White supremacist groups terrorize BIPOC people, often with impunity, immunity, and even support from agents of the justice system and White people who benefit from white supremacy. The murders of Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd represent key shifts in the movements for social justice and DEIA. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, masses of people worldwide took to the streets and digital platforms to protest police brutality and advocate for social justice. The visible and vocal protests and targeted boycotts against businesses and institutions deemed complicit or supportive of white supremacy led many to issue DEIA statements, pledge support, and promise to engage in DEIA evaluation and training.1

Just as Pope John Paul II’s Ex corde Ecclesiae sparked a wave of Catholic identity evaluation and reemergence, the Black Lives Matter and social justice movements called upon higher education institutions to review their DEIA stances and public image. Elliott states, “For Catholic colleges in particular, the importance of student diversity is often enumerated in their institutional mission statements; indeed, at these institutions, attracting a diverse student body is seen as integral for encouraging discourse among people of different beliefs and cultures and for promoting intellectual development” (Elliott 2012, 63). In the literature and national statistics, diversity is typically assessed in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender. Elliott notes Catholic scholarly literature is more likely to consider religious diversity or more broadly defined diversity (e.g., diversity of human race) than racial or ethnic diversity. Elliot and other scholars note Catholic colleges and universities tend to charge lower tuition than comparable private universities,2 and are thus more likely to attract a more diverse study body when considering race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and parental education as variables. However, Elliott found Catholic universities still enroll a more homogenous group than public colleges and universities (Elliott 2012). This makes it likely that visibly diverse students, staff, and faculty are more likely to stand out than those identifying with typical Catholic student body demographics.

We found a few studies of Catholic higher education DEIA published since the 2000s including Kabadi (2018), Davis et al. (2015), and Doyle and Connelly (2011). It is interesting to note the studies were more likely to use terms like social justice or microaggression than diversity, equity, inclusion, or accessibility, particularly when race or ethnicity is discussed. The avoidance of direct conversation about race and ethnicity when studying DEIA implications and progress at Catholic higher education institutions indicates an unwillingness to face--and thus address--real race and ethnicity issues at Catholic colleges and universities. Davis refers to this avoidance as social justice theatre, “a term used to delimit supposed boundaries between Catholic social justice and socially engaged pedagogies and practices” (Davis et al. 2015, 277).

But, the essential questions remain: (1) what are Catholic colleges and universities currently doing to advance DEIA and social justice on their campus communities; (2) to what extent might Catholic institutions be engaged in superficial actions or conversations regarding social justice and DEIA progress rather than implementing substantive action.

Methodology

The researchers wanted to explore how Catholic faith-based institutions in the US were managing and developing DEIA efforts on their campus, especially during the last two years. Additionally, the researchers were interested to learn about how USD compares to these Catholic faith-based institutions and ways the university can improve or learn from these other organizations.

The researchers created two surveys. Both surveys were approved by the researchers’ Institutional Review Board. The first survey was created for USD faculty, staff, and administrators who are involved in DEIA efforts on campus, whether through their direct job responsibilities, campus committees they serve on, or programs they participate in. The researchers investigated the various departments on campus, programming available related to DEIA, and colleagues they have worked with on programs related to DEIA. Through this research, they compiled a list of faculty, staff, and administrators to send out the survey to. The survey was open for about 6 weeks from January 15, 2021 to March 1, 2021.

The internal survey included seven qualitative questions. By limiting it to employees who are active in DEIA efforts and Copley Library employees, it helped the researchers gauge the current DEIA climate from employees who experienced these efforts firsthand. The survey asked questions related to experiences, programs, and general feelings related to DEIA programs within the university community.

The second survey, the external survey, was created for librarians who work at Catholic faith-based institutions, regardless of whether any kind of DEIA initiatives exist on their campus. The researchers believed the best way to distribute this survey was through various library listservs including ATLA, SCELC, ERIL, among others. The external survey used a mixed methods approach to better understand the group of librarians responding to the survey. The purpose of limiting research to librarians who work in Catholic faith-based institutions was to get a better grasp of how USD compares to other Catholic institutions promoting DEIA programming, services, and their overall demographic of employees and students.

The external survey included 23 questions and asked respondents about their personal background including their pronoun, race/ethnicity, and age group. The purpose of these questions was to get an idea of who was completing the survey. The following set of questions asked about the respondent’s specific role in DEIA, if any at their library and/or institution. Last, questions were asked about demographics of the campus as well as DEIA programming that occurs on their Catholic campus.

The researchers used Qualtrics for both surveys because it provides data analysis among other features to better understand the target audience. There were 10 respondents within the internal survey and 40 respondents within the external survey. With a small sample size for both surveys, the researchers chose to analyze the data themselves. The data was analyzed using Qualtrics analytic tools as well as NVivo.

There were a number of limitations the researchers faced. The researchers were anticipating 100 respondents in total for the internal and external survey. Because our research was specific to Catholic faith-based institutions, the researchers struggled to find a large pool of librarians to respond to the survey. The researchers received several requests from librarians from other faith-based institutions (i.e., not Catholic) in hopes to participate in the survey. Additionally, changes in workload and work mode due to the global pandemic had to shift many plans of in-person surveys with internal respondents, which were initially designed to complement synchronous Zoom interviews. The in-person interviews would give researchers an opportunity to dive deeper into many of the responses included in the internal survey. We also note that the findings reported here are limited to the responses given by those who took the survey. For example, accessibility issues were rarely addressed by internal or external respondents. Instead, respondents focused on diversity, inclusion, and equity issues. Responses reported in the findings below are the views as expressed by the individuals themselves, and do not reflect the views of the authors of this paper.

Findings and Discussion3

Internal survey results

We received responses from ten of our colleagues at the University of San Diego.

Six responded to our first question, asking them to frame the current state of DEIA at USD. Sentiments expressed in these responses tended toward the negative. One respondent spoke of “veneer and tokenism,” the marginalization and ignoring of voices of black students and faculty, LGBTQ+ students and faculty, and those with accessibility concerns. Negative sentiments included adjectives such as “poor,” “dismal,” and “disappointing.” The most positive responses were “much better than it was,” “perhaps trending toward improving,” and “evolving.”

We then asked respondents to share the goals and progress they would like to see in the next two years on our campus. The briefest of the six responses to this question refer to the need for deep change, implementing recommendations from our Antiracism task force, and an expression of “little hope” for meaningful change. The longer responses both mention improvements to accessibility, both in physical spaces and remote learning and meeting spaces. Respondents also mention hope for improvements in curriculum, compensation for black labor, retention efforts for BIPOC faculty, and recruitment and retention of a diverse student body.

Our next question asked respondents to describe their roles in achieving DEIA progress at USD. Respondents mentioned collection development, advocacy work, grant application, seeking professional development opportunities, service on the search committee for our new Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, efforts to link DEI to the university mission in the process of recruitment, service as a supportive ally for LGBTQ campus community members, and active conversations about DEIA with members of our campus community.

The final two questions of the internal survey brought the library into the conversation. We asked respondents at which point they consider library resources for support when planning or implementing a DEIA program or initiative. The five responses included a regretful sentiment: one who does not consider the library’s resources and another who expressed interest in learning how they might do so. Another shared that their turning to library resources had been limited to support for courses and their own knowledge, but not for initiatives. The other two respondents shared notions of making library patrons aware of resources in support of DEIA, as well as the library for event space, supporting curriculum, positive changes in cataloging, and critical information literacy.

Our final question asked respondents to go further and to consider what library support might look like. Of the four responses, one repeated the elements of event space, support of curriculum, changes in cataloging, and critical information literacy. Others expressed the necessity of remaining open to discussing DEIA with library patrons, acquiring recent and updated resources, facilitating community conversations, and modeling equity and inclusion with the library’s staff, policies, and procedures.

External survey results

Demographics

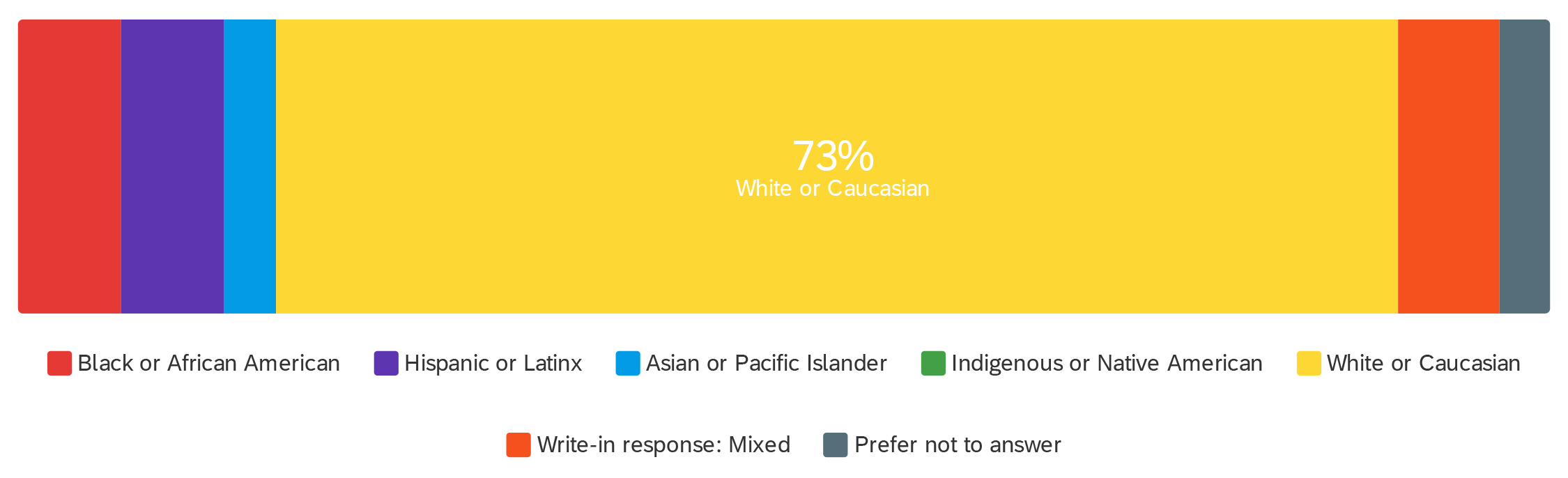

Figure 2: External survey respondents’ self-identified race or ethnicity.

Figure 3: External survey respondents’ preferred pronouns when describing themselves.

Figure 4: External survey respondents’ ages by 10-year increments.

Respondents were majority white: 73% identified as White or Caucasian; equal portions of respondents (6.7% each) identified as Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, and with write-in responses (“Mixed”); 3.3% identified as Asian or Pacific Islander; 3.3% preferred not to answer; and none of our respondents identified as Indigenous or Native American. Most respondents (76%) identified with feminine pronouns, and all respondents were over the age of 30. This data aligns with the overall trends in the demographics of our profession, leaning heavily toward White and female. ALA’s 2017 report on their ongoing Demographic Study of members shows that 81% identify as female and 86.7% as White (Rosa and Henke 2017). Similarly, the American Theological Library Association’s 2017 member survey results showed 52.5% of responding members identified as female and 91.7% identified as White (Brenda Bailey-Hainer, ATLA Members Newsletter, February 2017).

Topical questions

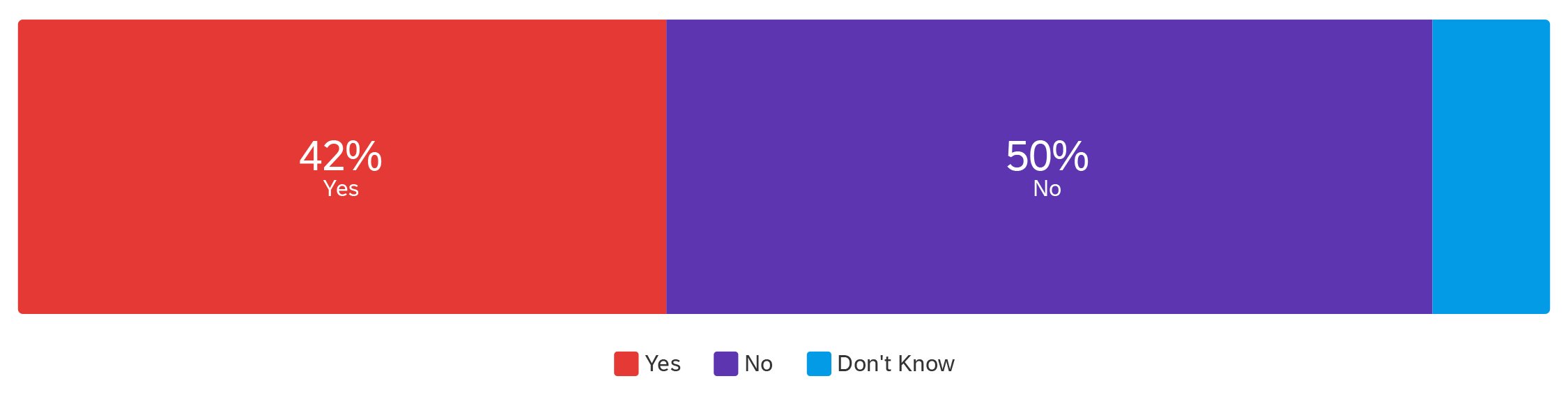

Figure 5: Existence of DEIA committee or task force in respondent’s own library.

We asked survey respondents whether their library has a committee or task force dedicated to DEIA (or other combination of the terms diversity, equity, inclusion, and/or accessibility) goals. Half of the twenty-six respondents said no, eleven (42.3%) answered yes, and two (7.7%) answered that they did not know.

We then asked those respondents who replied yes to share their committee’s goals with us. Themes revealed in the six responses (out of the ten who replied yes) included increased awareness, leadership, collection development, services, OER initiatives, staffing, collaboration with campus partners, continuing education or professional development, reviewing what other libraries do, working toward intentional dialogue or discussions. Collection development, collaboration with campus partners, and continuing education or professional development occurred in more than one response. A point of interest is that these responses were largely action-oriented and included units outside of the library, as opposed to strictly internal activities.

For those who responded that they did not have such a committee or that they did not know, we asked whether they believed such a committee would positively impact their library. Of the 11 responses to this prompt (73.3% of those who answered no or don’t know) one was an unqualified negative, and three were unqualified affirmative. One response was a hopeful affirmative (“I hope so”), and two responded with a probable affirmative (“perhaps” and “potentially”), with the added expression of concern that the bulk of the committee’s goals would lack “buy-in” from other members of the library. Three responses presented the idea that the work a dedicated DEIA committee in the library might do is already being done by other committees at the library or university level. One response answered this question with the statement that the student composition of the school, a Catholic seminary, is not diverse. These three themes (lack of “buy-in” or support, the idea that these things are being done already by others on campus, and the idea that the non-diverse campus does not warrant a DEIA committee or activities) appear repeatedly in the survey responses.

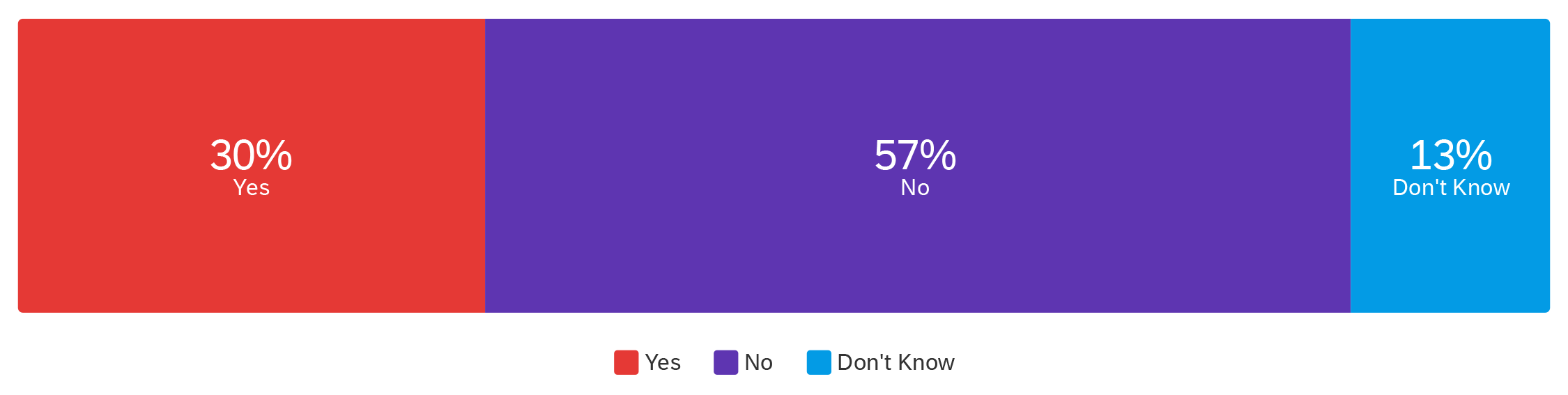

Figure 6: Existence of diversity-related statement or policy in respondent’s own library.

We asked respondents whether their library has a diversity statement or policy: 30.4% of the 23 respondents said yes; 56.5% of respondents said no; and 13% did not know.

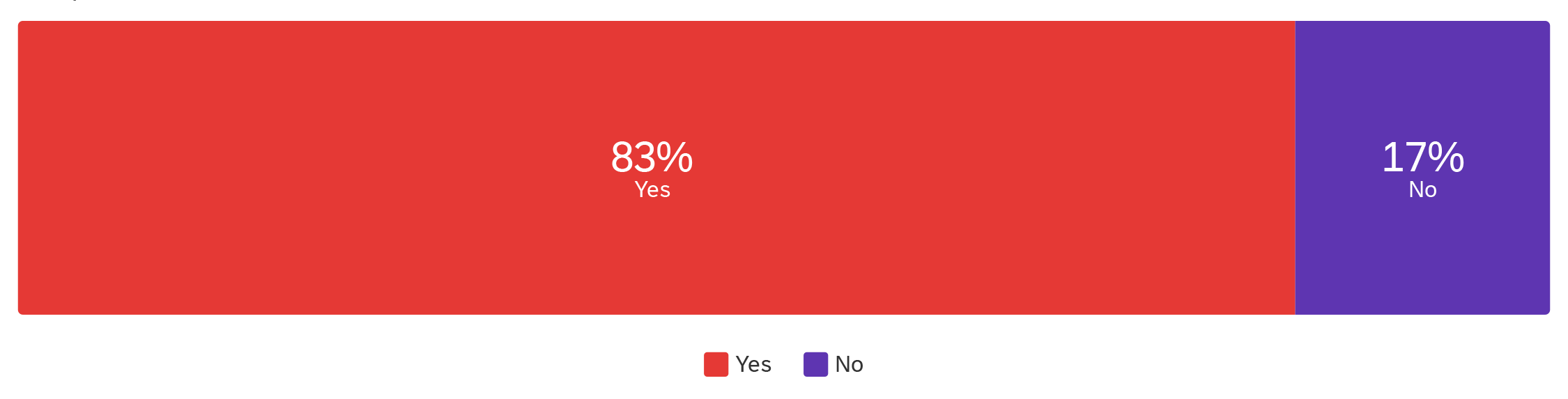

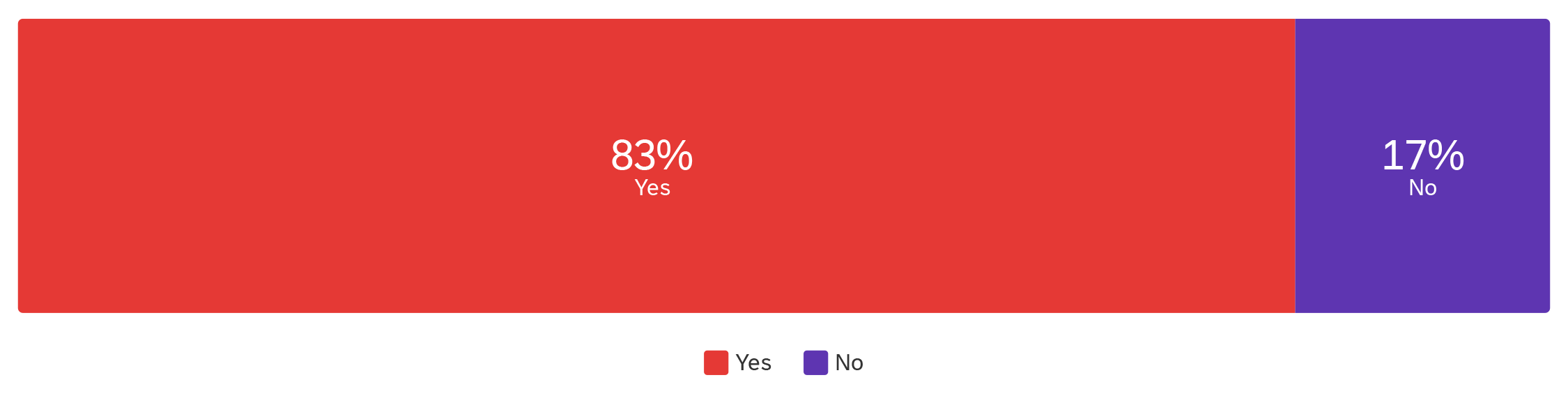

Figure 7: Existence of a dedicated department or office for DEIA at respondent’s own institution.

We asked whether respondents’ university had a department or unit on campus focused on DEIA. The majority of the (24) respondents said yes (83.3%); 16.7% said no.

We then asked respondents to describe their own roles in achieving DEIA progress at their institutions. Of the 17 responses to this prompt, two were unqualified, “none.” Other responses detailed activities within and beyond the library. Seven responses specifically mentioned leadership for or service on a library or institution level DEIA (or analogous) committee or task force. Others mentioned participation in faculty and student groups on campus, as well as participation in training and professional development. Several respondents detailed their work with collection development and promotion of collections, as well as LibGuide curation. There were also descriptions of development of a “DEI” statement for the library and ensuring representation of DEIA in a strategic plan. One respondent indicated that their daily work was in service of DEIA progress, and another replied simply, “Leadership.”

Our next question asked respondents to express their opinion on how Catholicism is reflected in their library’s DEIA commitment. Responses ranged from the firm negative (“not at all”) to “included” or “directly tied,” to specific actions such as collection development in support of DEIA, OER, and other efforts to support affordability and access. Others responded that DEIA is embedded in the mission of a Catholic institution (four responses referenced the institution mission explicitly, one more generally). Several of these responses pointed to specific Catholic traditions (Jesuit or Benedictine) and elements of Catholicism, such as working with marginalized people, social justice, and support or care of the whole person.

Respondents were asked to rank their institution and library on a scale of traditional to contemporary, with traditional on the lower end of the 0-10 scale, contemporary at the higher end. Most responses4 (73.7%) ranked their institutions in the 5-8 range, leaning toward the contemporary. Ranking their libraries, responses were also weighted heavily toward the contemporary, 88.9% falling in the 5-8 range, with a full ⅓ of responses falling at 8 on the scale. All but one respondent who ranked both university and library ranked their libraries equal or higher on the scale than their universities (the one respondent who ranked their library more traditional than their university ranked their university at a 10 and library at 8). When given the opportunity to give more context for their ranking choices, two respondents expressed some struggle with the terms “traditional” and contemporary,” which were undefined in the survey.

Respondents who ranked both university and library on the contemporary end of the scale shared comments about their rankings. Their comments indicated an equating of “contemporary” with “progressive” or “liberal,” and “traditional” with “conservative.” Respondents mentioned efforts at balancing the tensions between university and library. Comments indicated the sentiment that library strategic initiatives aimed at achieving DEIA goals are characteristics of the “contemporary” ranking. One respondent commented that the library is “one of the more progressive departments on campus in terms of DEI,” and one commented that leaning toward the “liberal” is the role of the library. One comment regarding the ranking of a university farther toward the traditional end of the scale than the library mentioned that the move toward being more contemporary as a university may be held back by the influence of alumni, the religious community, board members, and a more traditional-leaning administration. The tensions expressed by respondents in this question are reflective of those we saw in the literature, from faculty at USD and other Catholic institutions, regarding the balance between the requirements of the university mission and the needs of students and discipline.

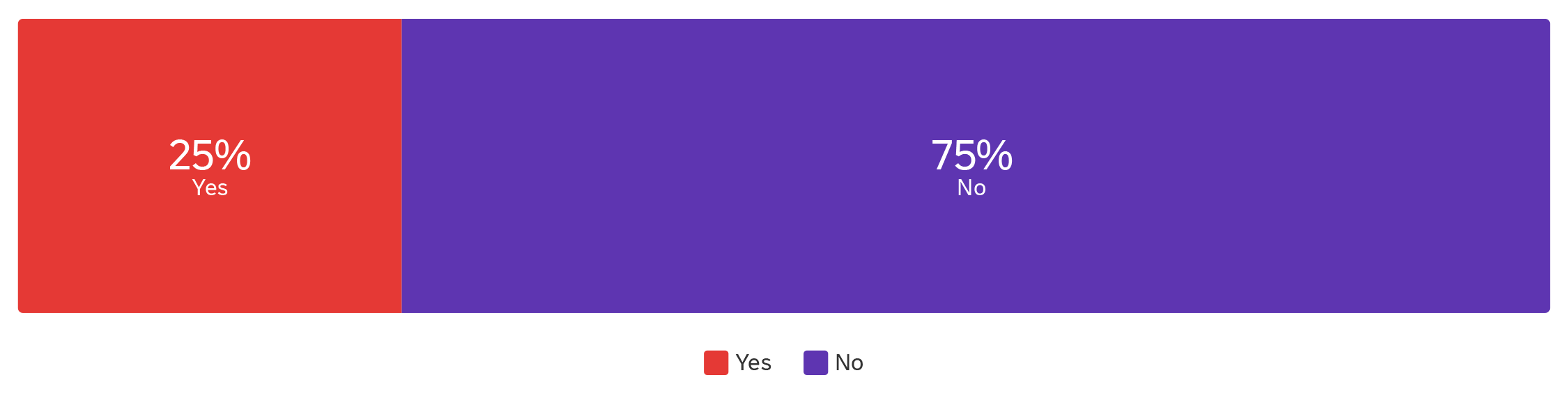

Figure 9: Existence of budgetary allocations for DEIA-related resources in respondent’s own library.

Four out of the 16 respondents to the question of whether their libraries have a budget specifically allocated to purchase DEIA resources, answered yes. 75% of the respondents’ libraries have no budget allocation specifically for DEIA resources. Comparing this result to answers to previous questions, it is worth noting that only three respondents’ libraries have a DEIA committee or task force, a DEIA statement or policy, and a specific budget allocated to DEIA purchases. While this question did not limit “DEIA resources” to collection-specific resources, it may be also worth noting that collection development is mentioned as a specific DEIA-oriented action in several respondents’ answers to previous questions, as well as the next question on the survey, both in terms of individual and library-level action.

Our next question asked respondents when they consider library resources for support when planning or implementing a DEIA program or initiative. Eleven people responded to this open-ended question. “Rarely” and “never” each appeared once in the responses. Two respondents offered descriptions of budget allocations for support of DEIA initiatives. Five respondents discussed DEIA as having a specific allowance for or being embedded in collection development practices. Two responses had firm, though brief, answers in the positive: “all the time” and “with every purchase.”

Figure 10: Intentional consideration of DEIA-related priorities in group discussions or collaborative decisions in respondent’s own library.

When asked whether they consider DEIA in faculty or staff meetings, or other group decisions, the majority of respondents (83.3%) answered yes.

Figure 11: Frequency with which DEIA-related considerations are explicitly or implicity addressed in group discussions or collaborative decisions in respondent’s own library.

The follow-up question asked respondents to share how often, on a scale, DEIA are addressed in considerations, either implicitly or explicitly. Of the three who answered, “no,” two answered, “sometimes,” and one, “never.” Of those who answered, “yes,” that they do consider DEIA in group decisions and meetings, most chose “sometimes” on the scale of frequency; the remaining responses fell almost equally between “about half the time,” “most of the time,” and “always.”

Figure 12: Experience or observation of opposition to DEIA advocacy in respondent’s own library or institution.

We asked respondents whether they had faced or witnessed any opposition or resistance to DEIA advocacy work at their library or institution. About ⅔ answered, “no.” Five out of the six who responded, “yes,” provided examples or explanations. These comments included ideas of “questioning” and “resistance,” especially in the context of hiring and evaluating recruits in terms of DEIA. One respondent stated, “We try to hire minorities, but there are so few of them who apply who are qualified.” One respondent commented that DEIA advocacy is interpreted as “speaking ‘against’ the university.” And there were a few who expressed ideas indicating an overall lack of enthusiasm for DEIA work in general, the encounter of ideas that “DEIA initiatives are not necessary,” and “People are just tired of the subject.” Of the eleven respondents who answered that they had not witnessed opposition or resistance to DEIA advocacy work at their institutions, there was minimal further comment. One shared that the majority of faculty and staff are committed to this work.

We then asked respondents how closely their library faculty and staff demographics reflected the demographics of their student population, on a scale of 0 (a poor reflection) to 10 (an excellent reflection). Eighteen people responded to this question, with a full one-third placing the alignment at 7 on the scale. The remaining responses were weighted primarily between 3 and 6, with single respondents placing the reflection firmly in the “poor” range (1 or 2 on the scale) or firmly in the “excellent” range (10 on the scale).5

Finally, we asked respondents whether they had any other comments to share about DEIA at their libraries or institutions. Several respondents took this opportunity to share more thoughts about demographics, which indicates that this is an area of concern for some. One respondent presented further details about the demographics of their institution, specifically that only 10% of their students, and just over 4% of library employees, are BIPOC. Another respondent commented that their “university is pretty white as is our staff, that’s something we’re working to change.” Two respondents commented on difficulties in recruitment and hiring of DEIA candidates.6 The first commented, “We do the best we can with DEIA. However, we are challenged to find qualified candidates to hire within DEIA particularly for diversity.” The second clarified, “We are a small staff in the library, and our location is a rural one, so it’s difficult to recruit diverse staff here.”

One respondent specified that their library is taking action and attempting to implement DEIA “in every day work decisions,” as well as aligning their work with campus-level initiatives. Another commented on the difficulty of engaging people at leadership and administrative levels, and expressed frustration that staff are asked “to carry this burden” of DEIA initiatives without support from leadership. Another respondent offered commentary on the difficulty of the measurability of DEIA goals: “How can you achieve goals if they are not objective and measurable? You can’t.”

Overall, the responses to our external survey seem to fall into two general categories: one includes those who recognize the need for DEIA policy and support for action in their libraries and on their campuses; the other includes those who believe the work of DEIA is enmeshed in Catholic identity, and is therefore already being done. We can see these categories in our respondents, as individuals express these opinions in their answers to various questions, and as individuals express frustration with the tension between their own efforts and campus response. Perhaps the disconnect reflects a difference in discussion and definition practices, campus cultures, and cultures within different units on campuses. Some of our survey responses seem to mirror the pronounced avoidance of race and ethnicity discussions as seen by Davis et al. (2015).

The results of both our internal and external surveys reveal an interesting concentration of themes of hopeful action and hopeless frustration. Respondents expressed willingness to invest in the work of supporting DEIA initiatives, but at the same time expressed the disappointment of witnessing initiatives not making it to the action stages or failing in implementation, reported in terms of lack of buy-in from colleagues, lack of institutional and administrative support, and even outwardly hostile response to initiatives.

One thing that is especially evident in the responses is the expression of the need for action and the recognition of library work as support for that action, if not a concrete example of that action. We see this most in the responses of our external colleagues in the field, who express their support for DEIA in terms of collection development and acquisitions. Perhaps this is where librarians feel most empowered to act. For librarians, action is the work we do in the library, with deliberate and intentional focus on DEIA. Taken together with what we see in our colleagues’ reporting of campus-oriented DEIA goals, we can see a forceful motivation to bring that empowerment beyond the walls of the library and share it with our campus partners.

Next Steps

Although the sample size from each survey was small, this exploratory study helped identify specific action items where a library DEIA committee can use their focus to improve the development and purpose of the committee and its support of the university community. This research is also meant to help other Catholic faith-based institutions who are looking to broaden the scope of their work with DEIA. The researchers plan to present findings through publications and presentations to gather more feedback and ideas to bring back to their institution as well as share ideas with other librarians.

Based on the data collected in both surveys, the researchers found ample evidence that shows what the Copley Library DEIA Committee and the university can do to provide more support. One of the biggest takeaways includes collection development and promotion of DEIA resources. The DEIA Committee plans to use allocated funds to build specific collections and begin analyzing the entire monograph collection to identify gaps and possible areas to develop in regards to DEIA.

As a means to promote resources to the university, the committee plans to collaborate with other departments on campus to build upon the current resources and programming developed by the library as well as those departments. Building a partnership with other departments will help promote library resources dedicated to DEIA and build connections that will help create a more inclusive institution. Creating a needs assessment based on the needs of affinity student groups and underrepresented faculty and staff will help the committee and researchers uncover programming and services that are necessary to increase retention.

In an effort to broaden the scope of this exploratory study, the researchers plan to develop a new survey and open it up to librarians from other faith-based institutions to identify missing gaps and compare results from our current Catholic faith-based survey. The survey will be similar to the survey sent out in December 2020, but there will be some modifications based on feedback received from survey respondents. In particular, we will endeavor to define terms that may have ambiguous, multiple, or context-specific meanings.

Conclusion

In light of the increasingly frequent and publicized events involving marginalized communities as well as powerful social movements including #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, Copley Library’s DEIA Committee wanted to become an action-driven committee that developed programming, services, and allocated resources to provide support to the university community. At the same time, Copley Library was also developing their current strategic plan, so it was pertinent for the committee to develop a well thought out plan. The three researchers also wanted to gauge the motivation and implementation of Catholic faith-based institutions’ DEIA programming. The inquiry led to two surveys to learn more about ways the committee can improve or find action items to add to their charge.

One of the biggest questions the researchers had was how libraries from Catholic faith-based institutions use the foundational teachings of Catholic identity and transform them into social justice action items. Based on the literature surrounding Catholic institutions and DEIA issues, it is evident that the mission of many institutions and the portrayal of their image leans toward amplifying inclusivity in religion, race, ethnicity, and gender. However, the extent of the mission is just a sentiment. We found limited evidence of real action to defend the Catholic philosophy. Similarly, survey results from the internal and external survey indicate a tendency to default to the beliefs of the Catholic religion without real action.

Copley Library’s DEIA Committee plans to continue working with constituents across campus and developing needs assessments to develop sustainable, helpful, and productive programming and tools to support movements and protest injustices that are not only happening on campus, but in the global community. The committee’s action-oriented focus is an intentional decision to move our advocacy work into a more active phase to challenge systemic oppression and change institutional culture. It is our goal to use our service, collections, and program expertise as a way for libraries to initiate new and support existing DEIA work.

References

Alba, R. 2006. “Diversity’s Blind Spot: Catholic Ethnics on the Faculties of Elite American Universities.” Ethnicities 6, no.4: 518–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796806072988.

Boylan, Ellen. 2015. “Where Catholic Identity Is Visible: Differences in College Students’ Mission Perception at Catholic and Independent Colleges.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 34, no. 2 (October 14): 211–34. https://jche-journals-villanova-edu.sandiego.idm.oclc.org/index.php/jche/article/view/1971.

Cardenas-Elliott, Diane. 2012. “Student Heterogeneity and Diversity at Catholic Colleges.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 31 (1): 61–81. https://jche.journals.villanova.edu/index.php/jche/article/view/1004.

Copley Library Strategic Planning Committee. n.d. “2021-2124 Strategic Plan,” 7. https://catcher.sandiego.edu/items/copley/Strategic%20Plan%202021-2024.pdf.

Davis, Reid, Peter Harrigan, Marietta Hedges, Maya Roth, Monica Stufft, and Christine Young. 2015. “To Thrive: Social Justice Theatre on Six Catholic Campuses.” Theatre Topics 25, no. 3: 277–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2015.0037.

Doyle, Denise, and Robert Connelly. 2011. “Building an Intentional Culture of Social Justice: Increasing Understanding and Competence in the Curriculum.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 30, no. 1 (September 21): 95–112. https://jche-journals-villanova-edu.sandiego.idm.oclc.org/index.php/jche/article/view/609.

Estanek, Sandra M, Michael James, and Daniel Norton. 2006. “Assessing Catholic Identity: A Study of Mission Statements of Catholic Colleges and Universities.” Journal of Catholic Education 10, no. 2 (December 1): 199-217. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.1002062013.

Gambescia, Stephen F, and Rocco Paolucci. 2011. “Nature and Extent of Catholic Identity Communicated through Official Websites of U.S. Catholic Colleges and Universities.” Journal of Catholic Education 15, no. 1 (August 22): 3-27. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.1501022013.

Heft, James L., and Fred P. Pestello. 1999. “Hiring Practices in Catholic Colleges and Universities.” Current Issues in Catholic Higher Education 20, no. 1: 89–97.

Heft, James L., Ronald M. Katsuyama, and Fred P. Pestello. 2001. “Faculty Attitudes and Hiring Practices at Selected Catholic Colleges and Universities.” Current Issues in Catholic Higher Education 21, no. 2: 43–63.

Janosik, Christopher M. 1999. “An Organizing Framework for Specifying and Maintaining Catholic Identity in American Catholic Higher Education.” Journal of Catholic Education 3, no. 1 (September 1): 15-32. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.0301032013.

Kabadi, Sajit. 2018. “Shadowed by the Veil of the Colorline: An Autoethnography of a Teacher of Color at a Catholic Predominantly White Institution (CPWI) in the United States.” Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal 7, no. 1 (January): 27–44. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217368279.pdf.

O’Connell, David M. 2012. “Our Schools--Our Hope: Reflections on Catholic Identity from the 2011 Catholic Higher Education Collaborative Conference.” In Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry & Practice, 16:155–86. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/cej/article/view/2595.

Rosa, Kathy, and Kelsey Henke. 2017. “2017 ALA Demographic Study.” ALA Office for Research and Statistics. https://www.ala.org/tools/sites/ala.org.tools/files/content/Draft%20of%20Member%20Demographics%20Survey%2001-11-2017.pdf.

Schuttloffel, Merylann “Mimi” J. 2012. “Catholic Identity: The Heart of Catholic Education.” In Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry & Practice, 16:148–54. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/cej/article/view/2594.

University of San Diego. n.d. Diversity at USD: Diversity, Inclusion, and Social Justice at USD. Center for Inclusion and Diversity. https://www.sandiego.edu/inclusion/diversity-at-usd.php.

University of San Diego. 2021. “Mission, Vision and Values.” https://www.sandiego.edu/about/mission-vision-values.php.

Appendix A: Internal Survey

- How would you frame the current state of DEIA affairs at USD? (Short answer)

- What DEIA goals/progress do you foresee for the next year? Two years?

- What is your role in achieving DEIA progress at USD?

- When do you consider the library/resources for support when planning or implementing a DEIA program or initiative?

- When you do consider library support, what does that look like?

Appendix B: External Survey

- Which pronouns do you use?

- Which race(s) or ethnicity(ies) identify you? Select all that apply if you identify as biracial or multiracial.

- Age range?

- Does your library have a DEIA committee/task force? (Yes/No/Don’t Know - Conditional)

- If so, what are their objectives/goals? (Short answer)

- If not/don’t know, do you think a DEIA committee/task force would positively impact your library? (Short answer)

- Does your library have a diversity statement or policy? (Yes/No/Don’t Know)

- Does your university have a department/unit on campus that solely focuses on DEIA? (Yes/No/Don’t Know)

- What is your role in achieving DEIA progress at your institution? (short answer)

- How is Catholicism reflected in your library’s DEIA commitment? (short answer)

- On a scale, is your university traditional to contemporary? Conservative to progressive? (Likert scale)

- Does your library have a budget specifically allocated to purchase DEIA resources?

- When do you consider the library/resources for support when planning or implementing a DEIA program or initiative? (short answer)

- Marketing or promotional materials? (short answer)

- Do you consider DEIA in faculty/staff meetings or other group decisions? Yes/No/Don’t Know - Conditional)

- How often are DEIA addressed in these considerations, either explicitly or implicitly? (Rarely, sometimes, always)

- Have you faced any opposition/resistance to DEIA advocacy work at your library or institution? (Yes/No/Don’t Know)

- Please explain or provide an example.

- How closely does your library faculty/staff population reflect the student population (demographics - race, ethnicity, gender, etc) at your institution (likert scale)

- Provide more detail. (optional and open-ended)

- Do you have any other comments about DEIA at your library and/or institution?

Endnotes

1 We consider the facts of these aspects of American history and culture to be long- and well-established for those in the academy, and in recent years in public discourse as well. For readers who require a review of the history of systemic racism and institutionally supported marginalization and disenfranchisement, we recommend searching Education, LIS, and Sociology literature with the terms [systemic racism] and [higher education].

2 USD’s annual full-time undergraduate tuition is approximately $54k for 2022-23. https://www.sandiego.edu/one-stop/tuition-and-fees/undergraduate.php Approximately 77% of students receive some form of financial aid. https://www.sandiego.edu/facts/quick/2020/finaid.php

3 The word clouds in this section visually represent content analysis of respondents’ open answer questions. The analysis revealed patterns in terms used to describe key issues.

4 One response was eliminated after the initial analysis because the respondent replied that their institution is not Catholic. Our survey was intended for librarians working at Catholic institutions of higher education, but did not have a mechanism to discourage others from responding.

5 LIS scholarship holds multiple perspectives on centering racial and ethnic demographics in library staffing versus community demographics. See Hudson. D.J. (2017). On “diversity” as anti-racism in Library and Information Studies: A critique. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1(1), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i1.6 for additional engagement on this topic.

6 LIS scholarship includes discussions that acknowledges the challenges of diverse LIS employee recruitment and retention. See Vinopal, J. (2016). The quest for diversity in library staffing: From awareness to action. In the Library With the Lead Pipe. http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity/ ; See also Cunningham, Guss, and Stout’s Challenging the “good fit” narrative: Creating inclusive recruitment practices in academic libraries, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/university-libraries-publications/42/