The Physical Canon

Its Formation and Depiction in Late Roman and Medieval Christianity

Abstract The physical Bible as we know it is a library of books gathered together within a single cover binding. The creation of the single-volume Bible, utilizing the codex book form, dates from the first half of the fourth century, and at its inception was a powerful technological innovation. Committing a fixed form within a binding, the single-volume Bible uniquely declared the unity of the Scriptures and the books authorized for inclusion. However, enormous production costs meant that single-volume Bibles were rare. Considering this rarity, Bibles must have come together in other recognized physical forms. Given the dearth of direct physical evidence, we infer their existence by looking at Greco-Roman book containers and furnishings, descriptive and metaphorical allusions in theological writings, the parallel development of the Torah Ark/Shrine in Jewish synagogues, and pictorial depictions in church mosaics and Bible manuscript paintings.

Introduction

“The Bible is a whole library stuffed inside a single book cover.”

I learned the books of the Bible at Sunday School when I was in fourth or fifth grade. Two things particularly stick in my mind from that time. First was a remarkable comment made by the teacher. She said: “This book I am holding in my hands is called the Holy Bible. This book looks like one book. But it’s actually a whole library of books stuffed inside a single book cover. In fact, there are sixty-six books in this library!” Sixty-six books sounded to me like a lot of books to fit into just one book cover. I remember being fascinated by this concept.

The second thing was the method the teacher used to help us learn the books of the Bible. She handed every student a small card.

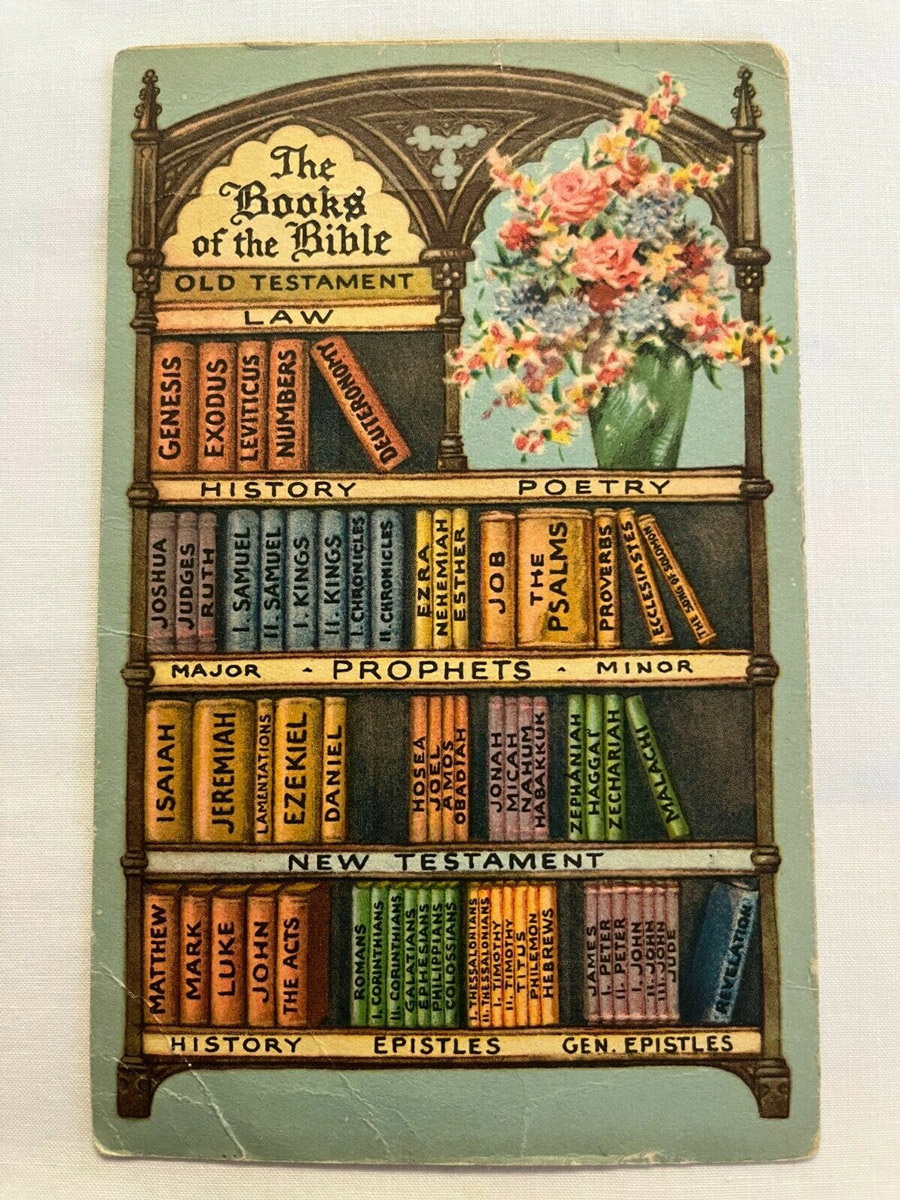

Figure 1: Books of the Bible bookcase card (photo used with permission)

On the card was a picture of a bookcase. In the bookcase were the books of the Bible depicted as individual volumes shelved in their proper order. Groups of books appeared in different colors, and the title of each was printed on the spine. On the bookcase were labels identifying, first, two large collections—the Old and New Testaments—and then the names of the major groups within each large collection. By using the picture of the Bible bookcase, our Sunday School teacher helped us to conceptualize the Bible as a library. Seeing the individual books on the shelves helped us memorize the names of the Bible books and their proper order.

I was reminded of the Bible bookcase picture card from Sunday School when I first saw a painting from the late-seventh century Latin Bible, the Codex Amiatinus.

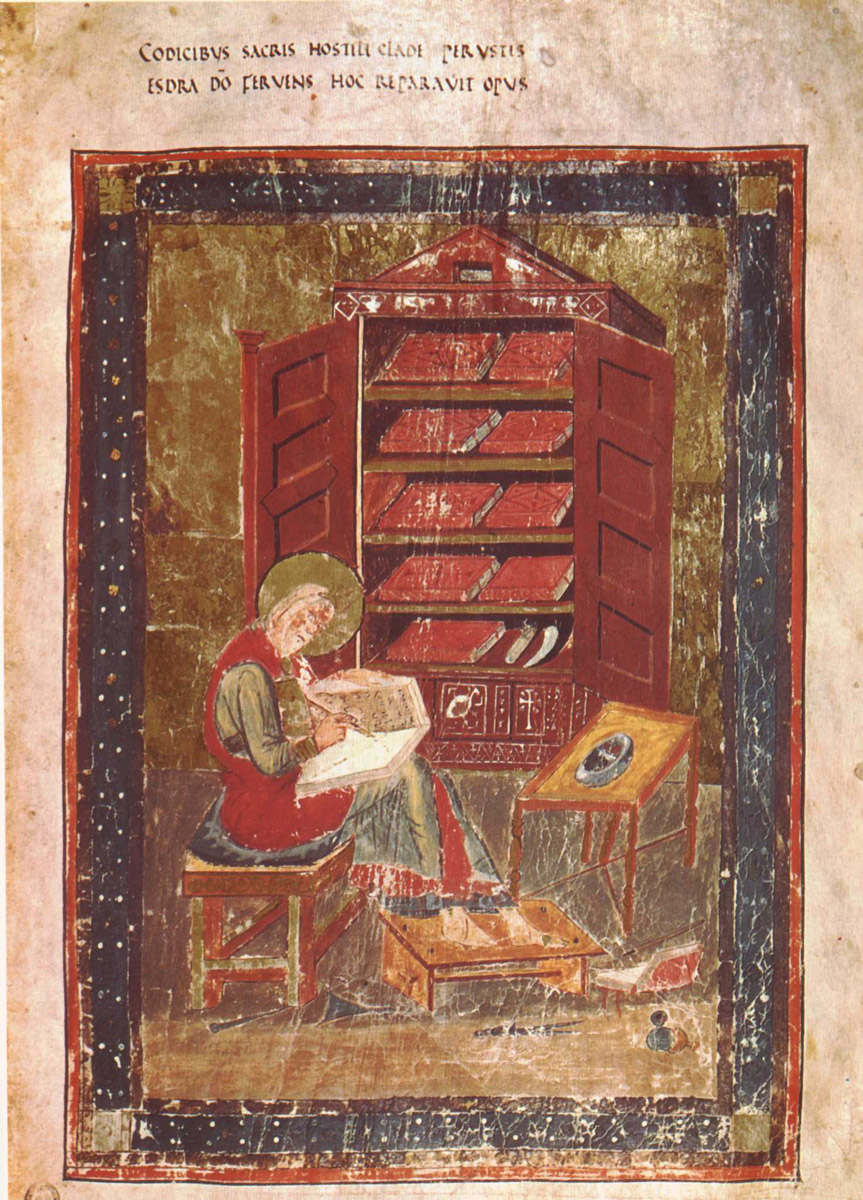

Figure 2: Ezra the Scribe in front of the armarium. Codex Amiatinus, late 7th–early 8th century (Photo from Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

In the opening pages of the manuscript there is a full-page painting that depicts a haloed scribe clothed in Hebrew priestly garb seated and writing in a codex. Behind the scribe is a large cupboard with two open doors. Inside the cupboard we see nine bound codices lying horizontally on five shelves with their spines facing outward. On each codex we see abbreviated titles of the major groups of the Bible inscribed in gold on the spine. I wondered if one function of this painting was similar to my Bible bookcase picture card from Sunday School. Perhaps the painting was there to help the viewer conceptualize this single-volume Bible as a library of many books within a single cover binding.

“Maybe the cupboard itself is significant.”

One day a number of years ago, I was visiting a Bible professor at Milligan University, where I serve as library director. On a wall of his office was a poster depicting a cupboard with two open doors.

Figure 3: Gospel armarium mosaic. Mausoleum Galla Placidia, Ravenna, early 5th century (photo Gianni Careddu CC BY-SA 4.0)

Inside the cupboard are four bound codices lying horizontally on two shelves. Titles in white hover above each codex identifying them as the Four Gospels. I later learned that this Gospel cupboard was part of a larger mosaic located in the early fifth-century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy.

Assuming it was not an artistic fabrication, the depiction of the Gospel cupboard appeared custom-built to comfortably hold the four codices. I wondered if the cupboard itself might be significant. Perhaps the cupboard was intended not only as a furnishing for storage, but that the books placed within it would immediately be recognized as Scripture—books and container together forming a physical canon.1 This impression was strengthened for me after seeing the Bible cupboard depicted in the Codex Amiantinus.

This provoked a question. Were dedicated Bible containers such as these a common and recognized furnishing in Late Roman and Medieval churches? It turns out that physical evidence to answer this question is difficult to come by. In order to test the plausibility of this proposal we would have to proceed inferentially, relying on comparisons with Greco-Roman book containers and furnishings, descriptive and metaphorical allusions in theological writings, the parallel development of the Torah Ark/Shrine in Jewish synagogues, and other pictorial depictions in church mosaics and Bible manuscript paintings.

The timeframe of our investigation is a 500-year period from the fourth through ninth centuries. The early end of this timeframe has a fourfold significance for the development of the Christian Bible: 1) Christianity became a recognized and protected religion in the Roman Empire; 2) the codex book form became ubiquitous;2 3) we witness first the innovation and then the practical abandonment of the single-volume Bible codex; and 4) we see the formalization of the biblical canon, disseminated physically through forms of an emerging Bible and abstractly through canon lists. The late end of the timeframe is significant because by the middle of the ninth century production processes and scribal infrastructures became standardized to the degree that single-volume Bibles became relatively common.

Notwithstanding the dearth of firm physical evidence, or maybe because of it, the question of dedicated Bible containers has seemed all but incidental to scholarship. As a practical matter, scripture manuscripts had to be stored somewhere when not in use. What of it? But it strikes us that this emphasis on practicality underestimates the significance of the container as sharing physically in the associative sacredness of the enclosed texts. The container, we suggest, demarcated the canonical status of the enclosed texts, even as it facilitated their access for the church’s use in worship and instruction.

The Innovation and Subsequent Practical Abandonment of the Single-Volume Bible Codex

During the reign of Constantine the Great, Christianity became a recognized and protected religion in the Roman Empire. In his Life of Constantine, Eusebius of Caesarea transcribes a letter he received from Constantine ordering the preparation of fifty copies of “the Divine Scriptures” for the churches in Constantinople (Eusebius 1999, 166-67):

Be ready therefore to act urgently on the decision which we have reached. It appeared proper to indicate to your Intelligence that you should order fifty volumes with ornamental leather bindings, easily legible and convenient for portable use, to be copied by skilled calligraphists well trained in the art, copies that is of the Divine Scriptures [θείων γραφῶν], the provision and use of which you well know to be necessary for reading in church.

Eusebius then relates his implementation of Constantine’s instructions saying: “Immediate action followed upon his word, as we sent him threes and fours in richly wrought bindings…” (Eusebius 1999, 167).

There has been considerable discussion over exactly what form of “Divine Scriptures” Constantine ordered Eusebius to produce. Scholars who focus on the call for “utmost speed” and “portable use” suggest that whole Bibles were not in view here. New Testaments, Gospels, or perhaps lectionaries seem to them more likely (Gamble 1995, 79-80). We, however, favor a view that Constantine ordered whole Bibles in some form. Eusebius, tasked with “diligence,” should give his top priority to this project. Moreover, when Constantine uses the term “Divine Scriptures” without qualification it seems most natural to take it that he is referring to a whole Bible, including both Old and New Testaments. If Constantine was ordering an abridged text this could have been easily stipulated (Skeat 1999, 605-6, note 28). Also, portability need not require an abridged text. Commenting on the somewhat opaque phrase that the copies were delivered in “threes and fours,” Averil Cameron and Stuart Hall surmise that since a single-volume Bible codex would not have been portable enough to facilitate all intended uses, the phrase could imply that whole Bibles were produced in multi-volume sets (Eusebius 1999, 327).

Although the form of the Constantinian Bibles cannot be determined conclusively, it is clear that the coincident development of the single-volume Bible codex at this time—the first half of the fourth century—was a remarkable technological and powerful symbolic innovation. Committing a fixed form within one cover binding, the single-volume Bible uniquely declared the unity of the Scriptures, the books authorized for inclusion, and their order. The gathered and bound codex effectively created a physical canon. Incidentally, in using the words “bible” and “canon” here we are not implying final forms as we recognize them today. Rather, these are the manifestations produced in the midst of an emerging process. That being said, we do take it that these manifestations were considered “bibles” and “canons” by the communities that produced and/or used them.

Notwithstanding this innovation, Harry Gamble and Theodore Skeat both agree that single-volume Greek Bible codices and later Latin pandects were extremely rare and exceptional in nature. Skeat estimated that during the first half of the fourth century probably no more than 100 had been produced, and of these, half were part of Constantine’s order (Skeat, 1999, 617)! The reasons for this scarcity are easy to appreciate. Production of a single-volume Bible was a large and costly undertaking. It is likely that single-volume Bibles were for many centuries possessed only by churches sufficiently affluent, or able to attract state sponsorship, as in the case of the Constantinian order.

We are suggesting that in view of the rarity of single-volume Bibles it is logical to suggest that whole Bibles took multi-volume forms, whether produced intentionally in multi-volume editions3 or collected together over time from various sources. It would seem logical to further suggest that the single-volume Bible format was for many centuries essentially abandoned as impractical, and that multi-volume Bibles were more common. Finally, it is logical to suggest that these multi-volume Bibles were gathered in dedicated containers, not simply for practical storage but also to preserve their character as a physical canon in much the same way that single-volume Bibles gathered between the covers of an ornamented binding would.

The Formalization of the Biblical Canon, Disseminated through Physical Forms and Canon Lists

As librarians, we note that the collection of texts that form the Bible need to be ordered and that ordering occurs in the conceptual as well as the physical realms. Philosopher and technologist David Weinberger (2007) introduced the concept of “orders of order” to describe the organization of things and information. He identifies three orders of order, though we will only examine the first two here.

The “first order of order” is how physical things are organized in space. In a single-volume Bible codex, the “first order” is the selection and arrangement of books possessing scriptural authority which are literally sewn into place and bound within protective and ornamented leather or wooden cover boards. In a book box, chest, or cupboard, the “first order” is the selection and arrangement of books (rolls or smaller codices) that are placed loosely within a dedicated container. The single-volume codex does a much better job fixing its contents. This is one of its organizational powers.4 But again, the single-volume Bible, despite being highly innovative, was a rarity. We argue that other “first order” forms must have been available to play a similar function. The books gathered unbound in a cupboard are still selected and arranged with intention. Books that do not possess scriptural authority are excluded from the container. The container itself serves to point to and demarcate the special nature of the contents enclosed, much as the binding covers of a single-volume Bible.

The selection process for canonical texts entailed several overlapping and related issues. While it seems unlikely that when the Apostle Paul wrote his letters he thought of them as Scripture (1 Cor. 7:12), later Christians who copied, distributed, and preserved these writings certainly did. Among the early criteria for a book to be part of the biblical canon was its applicability for use in Christian worship and instruction in the Christian faith. Unfortunately, there is no record of how books were chosen to be part of an emerging canonical Bible. However, several competing factors were doubtlessly considered during deliberation on a book’s canonical status. Lee Martin McDonald (2007, 401-421) notes that these factors included apostolicity, orthodoxy, antiquity, the aforementioned use for worship, inspiration, and perhaps others. Related to the factor of usage is accessibility. Churches would not have used texts to which they had no access.

Edmon Gallagher and John Meade note that in the writings of Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, we find the first use of the term canon (κανών) as a concept for the totality of the Christian scriptures (2017, xiii). In De Decretis 18, Athanasius remarks that the Shepherd of Hermas does not belong as part of the canon. Despite this newer use of the word canon, the term was not the only one used to describe the Scriptures in the fourth century. Gregory Robbins (1993) has shown that Eusebius of Caesarea preferred to use the term catalog (κατάλογος) to speak of the Scriptures.5 Even after Athanasius’ famous Festal Letter of 367, the canon of the Bible was not closed (Gallagher and Meade 2017, 30; Brakke 1994, 395-419).6 Lists of biblical books continued to be produced and different canons still existed.

We suggest that canon lists served as metadata for the emerging Bible that had a physical manifestation in the objects of written texts. The list articulates the data of what is found on the shelf. Lists provide a convenient summary identifying the books deemed authoritative for worship and instructional use in the churches at key locations and moments in the process. In Weinberger’s framework, a canon list is an example of a “second order of order.” It is metadata, or “information about” the physical thing(s) being described. The list does not contain the books themselves—neither their content, nor their physical manifestations. Weinberger reminds us that the “second order” always points back to real physical things and their “first order” selection and arrangement. From this we warrant that canon lists would have necessarily been composed from existing “first order” collections, whether in single-volume or multi-volume forms—what we’re calling a physical canon.7

Greco-Roman Book Containers

Recalling the Sunday School story from our introduction, the books of the Bible gathered within a single book cover form a library. The Greek word for library is βιβλιοθήκη (Latin bibliotheca) and refers to any collection of books. Implicit in the etymology of βιβλιοθήκη is an archaic reference to a container, a θήκη, “box” or “chest” for storing the collected books (βιβλία). This etymological reminder provides a caution against overly abstracting or “second ordering” the concept of the biblical canon so that we fail to see possible physical “first order” manifestations. An obvious place to start looking for physical manifestations would be examples of book containers and related furnishings in use in the Greco-Roman world of the time.

In addition to a plain wooden plank affixed horizontally to a wall with supporting brackets creating a simple shelf, or the more custom-built shelf that added vertical dividers or “pigeon-holes,” there were three common containers known for storing books—the capsa, the scrinium, and the armarium. The capsa is a cylindrical box made of wood with a fitted and latched lid and carrying strap or handle. Although sizes varied, a capsa would have been considered portable, like a modern-day backpack. Books, typically in roll form, were stored vertically inside. A scrinium was similar to a capsa only larger, or often chest-like. The armarium was a wooden cupboard, typically with double doors and a flat or gabled roof, used to store tools or valuables of all kinds. It appears to have been a Roman development (Richter 1969, 377-79).8 Stephan Mols, who researched armaria and aediculae (small temple buildings or shrines) at Herculaneum, provides an important insight supporting our search for manifestations of a “first order” physical scriptural canon. He writes: “The aediculae in Herculaneum belong to a group of storage furniture from antiquity which is characterized by a pediment façade. Besides household shrines, this group contains cupboards where portraits of ancestors were set up, cupboards in which imperial laws and decrees were kept, Jewish Torah cupboards, and early Christian Bible cupboards. … These formal resemblances reflect the cultic or religious function of all these types of furniture” (Mols 1999, 61, emphasis added).

Armaria are similar in basic design to household shrines (aediculae), which are themselves miniature versions of Greco-Roman temples. Mols’ reference to Jewish Torah cupboards and Christian Bible cupboards in this context—that is, containers used to hold sacred scriptures—is of special interest to us because depictions of both appear to have adopted the Greco-Roman aedicular design. These architectural features were often supplemented with decorations of pagan iconographic motifs such as peacocks, the tree of life, twining greenery, urns or amphorae, stars, flowing water, etc. that have been appropriated and reinterpreted consistent with Jewish and Christian religious sensibilities (Anđelković, Rogić, and Nikolić 2010, 231-48; Ramirez 2009, 1-18).

The Synagogue Torah Ark/Shrine

Intended to hearken back to the wilderness Ark of the Covenant (Exod. 25), the synagogue Torah Ark/Shrine evolved in form and function to serve in the early centuries of the Common Era as the worship focus and permanent repository for Jewish scripture scrolls.9 In this way it effectively became a physical scripture canon. Over time, architectural changes were made in synagogue worship spaces to accommodate a semi-permanent wall niche for the ark, or the ark was affixed to or integrated into the Jerusalem-oriented wall to create a permanent Torah Shrine.

Pictorial depictions on synagogue floor mosaics, gold glasses, and the like show the shrine as a double-doored armarium with common Greco-Roman aedicular elements, such as mentioned previously (Fine 2016, 121-34).10

Figure 4: Gold glass base with Torah Shrine, 4th century. Israel Museum Collection (photo Françoise Foliot CC BY-SA 4.0)

These appropriated elements accentuated the ark’s sacredness. Given the shared scriptural tradition and including the fact that many early church communities were formed by converts from Judaism, it is not unreasonable to suppose that beyond a commonly utilized aedicular motif, the synagogue Torah Ark/Shrine with its enclosed scripture scrolls provided a model for emulation.

Descriptive and Metaphorical Allusions

Our research surfaced a variety of primary textual sources inferring the existence of dedicated containers and spaces that manifest a “first order” physical scripture canon. We can only look at a few here.

Origen

In his Second Homily on Genesis, Origen of Alexandria exposits the moral meaning of the Book of Genesis’ description of Noah’s Ark. In the same way that Noah constructed the ark to provide for the salvation of him and his family and the animals, any person who can “hear the word of God and the heavenly precepts” is, as it were, building an “ark of salvation within his own heart.” Origen (1982, 85-8) compares this “ark of salvation” to a library:

He does not construct this library [bibliothecam] from planks which are unhewn, but from planks which have been squared and arranged in a uniform line, that is, not from the volumes of secular authors, but from the prophetic and apostolic volumes [ex propheticis atque apostolicis voluminibus]. … If, therefore, you build an ark, if you gather a library, gather it from the words of the prophets and apostles or of those who have followed them in the right lines of faith.11

Origen metaphorically equates the process of internalizing God’s word to the building of a library. While he doesn’t describe a completed container that holds the scripture books, he does refer to the building materials: “planks which have been squared and arranged in a uniform line.” He states that the library is comprised of “the prophetic and apostolic volumes.” “Prophets and Apostles” was an early Christian way of referring to the combined Jewish and Christian Scriptures. But he is not referring to these scriptures abstractly. His explicit reference to “volumes” suggests books arranged upon a shelf or in a cupboard. Given that the metaphorical usage of this scriptural library is here connected to Noah’s Ark, we might have expected Origen to reference the Torah shrine or ark in the Jewish synagogue as a parallel. He does not. Still, a physical reality surely stands behind the metaphor.

Jerome

The metaphor of the internalized scripture library also shows up in Saint Jerome’s letter to Paulinus, Bishop of Nola (Epistle 53) (2004, 97-8). Speaking about Paul, Jerome asks: Why was Paul a “chosen vessel” for the apostolic ministry (Acts 9:15)? He answers: “Because Paul was a cupboard of the Law and the Holy Scriptures [legis et sanctarum Scripturarum armarium].” In the time of Paul’s religious education as a pharisaical Jew under Gamaliel there were no Christian scriptures, and the only scripture armarium was the Torah shrine. But by Jerome’s day, the physical armarium, here metaphorically embodied by the apostle Paul, has been enlarged to contain not only the Jewish scriptures (“the Law,” here broadly applied), and also the volumes of Letters and Gospels of the Church, the Holy Scriptures.

Cassiodorus

A couple of further examples come from the sixth-century Roman statesman and scholar, Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator. In his Explanation of the Psalms, Cassiodorus (1991, 116) also refers to the scripture library metaphorically. But unlike Origen and Jerome, he applies the metaphor not to persons, but to Psalm 109 and the Book of Psalms as a whole. In the preface to Psalm 109 he writes: “So [this] psalm is, so to say, the sun of our faith, the mirror of the heavenly secret, the chest of the holy Scriptures [armarium sanctarum Scripturarum], in which all that is told in the proclamation of both testaments is spoken in summary.” And in his conclusion to the Book of Psalms, Cassiodorus (1991, 466-67) writes: “What in fact is there that one cannot find in this heavenly chest of divine scriptures [caelesti armario scripturarum]? … The book [of Psalms] embraces both New and Old Testaments in such a unique way that you can truly realise that a spiritual library [spiritalem bibliothecam] is built up in this book.”

Cassiodorus, like Origen and Jerome earlier, is picturing volumes of scripture books gathered as a library stored within a chest or cabinet. We contend that behind this metaphorical use stood actual scripture chests that contained multiple volumes encompassing “both New and Old Testaments.” Also, for Cassiodorus the chest is clearly not simply a container for storage. He deems the chest itself as “heavenly” by virtue of its spiritual contents.

Pictorial Depictions

We now turn to a series of pictorial depictions of Bible containers from mosaics and manuscript paintings dating from the fifth to ninth centuries. We argue that these depictions were based on actual physical objects within the church.

Gospel Cupboard Mosaic, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is a cruciform chapel located in Ravenna, Italy, built sometime after 425. The interior of the chapel is extensively decorated with brilliant wall and ceiling mosaics in a unified style. In the space above the sarcophagus across from the main entrance is a remarkable composition (Figure 5) involving three elements: a robed and haloed man carrying a processional cross over his right shoulder and an open codex in his left hand; a metal gridiron placed over a raging fire; and a Roman-style book cupboard (armarium) with pediment, two doors open to reveal two shelves upon which sit four codices, two to a shelf (Figure 3 shows the armarium detail). Above each codex hover the titles identifying them as the Four Gospels.

Figure 5: Saint Vincent mosaic. Mausoleum Galla Placidia, Ravenna, early 5th century (photo Gianni Careddu CC BY-SA 4.0)

Art historians have traditionally identified the man in the mosaic as Saint Lawrence, deacon at the church in Rome, who was martyred in 258 during a persecution of Christians ordered by the emperor Valerian. An alternative proposal by Gillian Mackie (1990, 54-60) suggests that the man in the mosaic is not Lawrence but the early fourth-century Spanish martyr, Saint Vincent of Saragossa. Vincent was memorialized by the late fourth-century Christian poet, Aurelius Clemens Prudentius after he was martyred in 304 during the Diocletian persecution. Of interest, the persecution was initiated after Diocletian issued an imperial edict specifically requiring the surrender and subsequent burning of church scripture books. Regarding the mosaic, we propose that any viewer looking at the Gospel books gathered within the cupboard is seeing an image readily understandable to them.

Mosaic of Luke the Evangelist in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

The Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, was completed and dedicated in 547. The octagon-shaped church is designed with a mix of Byzantine and Roman elements. The walls and ceiling are covered with brightly colored mosaics depicting biblical scenes, church and imperial portraits, naturalistic scenery with plants and animals, and geometric patterns.

The upper gallery level of the northeast- and southwest-facing walls of the sanctuary include corner panels portraying the Four Evangelists. Common design elements can be observed in each. Each evangelist is seated outdoors in a verdant, terraced landscape with water features and aquatic birds in the foreground. Each evangelist is haloed and gazing upward. At the top of each panel is the symbol traditionally associated with the evangelist as derived from Ezekiel’s vision of the four living creatures (Ezek. 1:1-21; cf. Rev. 4:6-8). Each evangelist is holding a leatherbound codex of their respective Gospel.

In the Luke panel we see the evangelist sitting next to a capsa, the Roman cylindrical book box discussed earlier.

Figure 6: Luke the Evangelist. San Vitale, Ravenna, mid-6th century (photo Paul Bissegger CC BY-SA 4.0)

In this depiction, the lid of the capsa is open revealing eight book rolls. There is no indication of the content of the rolls. However, in the context of the panels and the larger basilica mosaic program, these are almost certainly scripture books, likely texts of the Old Testament. In other words, the evangelist writes of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ, fulfilled in what was foretold about him in the Jewish scriptures.

Ezra the Scribe and Bible Cupboard Miniature from the Codex Amiatinus

The previously mentioned Codex Amiatinus, is a single-volume Bible produced at the monasteries of Wearmouth-Jarrow in Northumbria, and dated to the late seventh or early eighth century. It is the oldest surviving complete Latin Vulgate Bible.12 As it happens, research into the pre-history of the pandect’s production involves the previously referenced sixth-century scholar, Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator.

In his Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning, Cassiodorus (2004) alludes to the possession of four complete Bible pandects at his monastery. Of particular interest to us is a nine-volume Bible, which appears to be the very Bible depicted in the full-page painting in the Codex Amiatinus.

In the painting (Figure 2), we see a seated, haloed figure transcribing text with a stylus into a codex resting on his lap. The figure appears to be dressed in Old Testament priestly garb. Art historians identify this as Ezra the scribe, or an honorific depiction of Cassiodorus himself. Behind the figure stands a large wooden cupboard in classical pedimented design with two open doors. On the outside face of the cupboard, we see painted geometric patterns and images of crosses, urns, oxen, and birds, including a pair of facing peacocks in the pediment, all of which evoke characteristics of classical pagan aediculae and synagogue Torah Ark/Shrines, as previously discussed. The overall design also closely matches the cupboard depicted on the Galla Placidia Mausoleum mosaic described before.

Within the cupboard we see five shelves with nine decoratively bound codices lying horizontally, two to a shelf, spines facing outward. The spine of each codex is labeled in gold ink with an abbreviated name of a Bible section and the number of books within that section, following Saint Augustine’s arrangement.

Notwithstanding the anachronistic placement of the character of Ezra within a late antique/early medieval setting, there is no reason to suppose that the artist’s depiction of the cupboard with encased scripture books is not wholly realistic.13 As suggested in the Introduction, the painting communicates that this present Bible, bound within a single cover binding, is functionally the same as a multi-volume Bible with its codices placed on shelves within a dedicated container.

Maiestas Domini Miniature from the First Bible of Charles the Bald

The First Bible of Charles the Bald, also known as the Vivian Bible, was commissioned in 845 and presented to Charles, king of West Francia, in 846.14 The richly illuminated large-format Bible pandect is representative of high-quality Bibles produced in scriptoria during the ninth century.

Our attention is drawn to a full-page painting of the Maiestas Domini (Christ in Majesty), which serves as the frontispiece to the New Testament and the Gospels. The Maiestas is a tight, multi-layered composition. At the center within a double orb is the resurrected and glorified Christ seated on the orb of the heavens. He is supporting a golden codex (the Book of Life?) with his left hand while holding a chi-rho medallion in his right. Moving outward from the center is a diamond shape with medallions projecting out from each corner. Within the diamond are the haloed symbols of the Four Evangelists, each holding a codex. Within the corner medallions are the Four Major Prophets each haloed and holding scrolls. The interpretation of the composition to this point is fairly clear: the entire Scriptures, both the Prophets (Old Testament) and the Apostles (New Testament) provide a unified witness to the Christ, foretold and fulfilled.

Moving outward to the corners of the composition, we see depictions of the Four Evangelists themselves. They are each writing in a codex while gazing toward their respective symbol within the diamond. The interpretation here is also clear: each symbol embodies the source of heavenly inspiration received as they compose their respective Gospel, a record of the Apostolic witness to the Christ event.

One additional feature in each of the evangelist depictions attracts our attention. At their feet we see open-lidded cylindrical containers and rectangular chests.

Figure 7: Maiestas Domini miniature (Luke detail). First Bible of Charles the Bald, mid-9th century (source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Non-commercial reuse permission)

These containers are clearly Roman capsae and scrinia. Here the containers here are filled with both scrolls and codices. We noted before that the Four Prophets were depicted holding scrolls while the Four Evangelists held codices. A consistent application of these pictorial elements suggests that the capsae and scrinia are scripture containers, holding books from both the Old and New Testaments.

Saint Jerome Miniature from the First Bible of Charles the Bald

One other full-page painting from the Vivian Bible we looked at was the Saint Jerome frontispiece, which is located close to the very front of the Bible. The painting is composed of three panels depicting key moments in the life of Jerome related to the creation of his influential Latin translation. We are here especially interested in the second panel, which shows four nuns to Jerome’s right and three monk/clerics to his left.

Notice especially the architectural structure on the far right of the panel.

Figure 8: Saint Jerome miniature (cupboard detail). First Bible of Charles the Bald, mid-9th century (source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Non-commercial reuse permission)

The tower-like structure is shown with scrolls spilling out of its second-story door and third-story window, and double doors open outward on the ground floor. The cleric on the right, with stylus and codex notebook in hand, is looking intently at one of the scrolls. The structure is not a real building at all, but a piece of cabinet furniture. In its Palestinian context, we are likely viewing a synagogue Torah Shrine where the Jewish scripture scrolls were kept. However, based on another Bible manuscript that we will allude to in a moment, it is possible that the cabinet here is actually modeled after a church scripture book cupboard.

Frontispiece Miniature of John the Evangelist from the San Paolo Bible

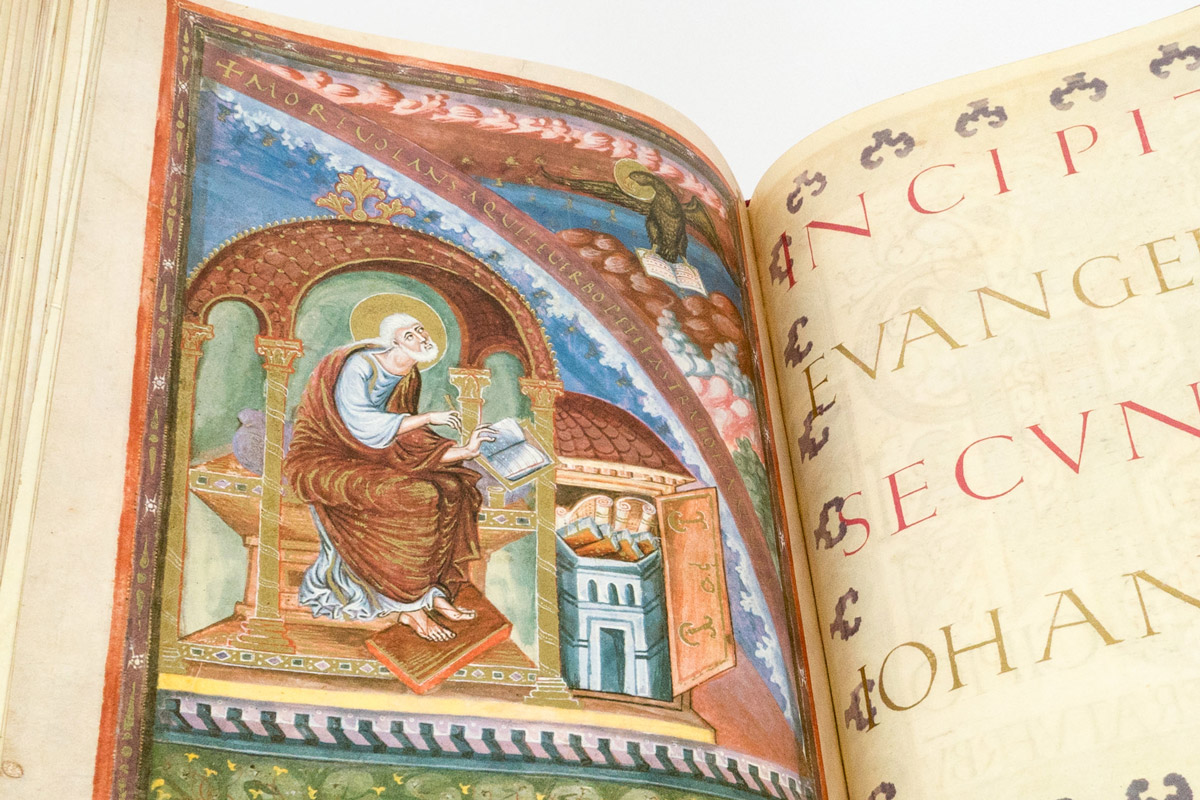

We want to look at one final pictorial depiction, this time from the San Paolo Bible, named for the Benedictine abbey, Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome, where the Bible resides to this day. The San Paolo Bible was commissioned for the coronation of Charles the Bald as Emperor of the Carolingian Empire on Christmas Day 875. Of interest, the San Paolo Bible includes full-page frontispiece paintings of each evangelist at the beginning of their respective Gospel within the manuscript.15 We are looking here at the frontispiece to the Gospel of John as representative.

Figure 9: Frontispiece miniature of John the Evangelist. Bible of St. Paul Outside the Walls, late 9th century (Facsimile Edition, https://www.facsimilefinder.com/. Photo Giovanni Scorcioni. Used by permission)

The depiction retains common characteristics of the “seated evangelist as scribe” motif we saw in the Vivian Maiestas and in the earlier San Vitale mosaics. John is haloed and in the process of transcribing his Gospel under the inspiration of his symbol. Perhaps alluding to the Gospel Book processed to the front of the church during the liturgy, notice that John is seated on the altar under the columned canopy in the sanctuary. Notice also the room with an open door under a domed roof to the right of the sanctuary altar. Within this room we see an architecturally shaped container filled to overflowing with rolls and codices. We take this to be a depiction of a scripture book container located in the sacristy to the right of the sanctuary altar.

Adding interest to this scene, it turns out that each of the Evangelist frontispieces in the San Paolo Bible features a different kind of scripture book container. Matthew is shown with a high chest (scrinium), also located in an adjoining sacristy. Luke is shown with a combination cabinet-lectern situated immediately to his right next to the altar. Meanwhile, Mark is shown with a three-storied tower, which resonates closely with the tower-like cabinet depicted in the Jerome frontispiece from the Vivian Bible discussed before. The cumulative takeaway for us is that here, near the end of our period of investigation, we are granted representative depictions of a variety of multi-volume scripture book containers along with hints about their placement within the church. Their depiction within a single-volume Bible pandect strikes us as appropriately honorific—marking a transition in the format of the physical canon from cupboard to binding.

Conclusion

In this presentation, we proposed the existence of dedicated Bible containers as a common and recognized furnishing in Late Roman and Medieval churches. However, due to the absence of direct physical evidence we had to test the plausibility of our proposal inferentially. We looked at Greco-Roman aedicular design elements and their adoption in Jewish and Christian worship space settings. We looked particularly at depictions of Torah arks and shrines in Jewish synagogues and reasoned, through frequent association, the parallel development of scripture chests or cabinets in contemporary Christian churches. Next, we looked at descriptive and metaphorical allusions to scripture libraries and containers in the writings of early Christian theologians. Finally, we looked at several pictorial depictions of scripture book containers from church mosaics and Bible manuscript paintings. These included depictions of the two scripture cupboards that first launched our investigation and extended to depictions of various scripture book containers in several richly illustrated mid-ninth century single-volume pandects—the very period when the single-volume Bible was reasserting itself as a viable format. In the end, this investigation highlights the physical nature of the biblical canon and the impacts that the Bible’s physicality has on canon formation and dissemination.

Works Cited

Anđelković, Jelena, Dragana Rogić, and Emilija Nikolić. 2010. “Peacock as a Sign in the Late Antique and Early Christian Art.” Archaeology and Science 6: 231-48.

Cassiodorus. 1991. Explanation of the Psalms, Volume 3 (Psalms 101-150). Translated by P.G. Walsh. New York: Paulist Press.

———. 2004. Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning and On the Soul. Translated by James W. Halporn and Mark Vessey. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Eusebius. 1999. Life of Constantine. Translated by Averil Cameron and Stuart G. Hall. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Fine, Steven. 2016. “The Open Ark: A Jewish Iconographic Type in Late Antique Rome and Sardis.” Viewing Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology: VeHinnei Rachel—Essays in Honor of Rachel Hachlili. Edited by Ann E. Killebrew and Gabriele Fassbeck. Leiden: Brill, 121-34.

Gaehde, Joachim. 1971. “The Turonian Sources of the Bible of San Paolo Fuori Le Mura in Rome.” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 5, no. 1: 359-400.

Gallagher, Edmon L. and John D. Meade. 2017. The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gamble, Harry Y. 1995. Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hachlili, Rachel. 2000. “Torah Shrine and Ark in Ancient Synagogues: A Re-evaluation.” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, Bd. 116, H. 2: 146-83.

Hurtado, Larry W. 2006. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Jerome. 2004. Letter LIII To Paulinus. Translated by W.H. Fremantle. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Volume 6, St. Jerome: Letters and Select Works, Reprint Edition. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 97-8.

Mackie, Gillian. 1990. “New Light on the So-Called Saint Lawrence Panel at the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna.” Gesta 29, no. 1: 54-60.

McDonald, Lee Martin. 2007. The Biblical Canon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

Meyers, Eric M. 1997. “The Torah Shrine in the Ancient Synagogue: Another Look at the Evidence.” Jewish Studies Quarterly 4. no. 4: 303-38.

Milson, David. 2007. “The ‘Façade Motif’ in Ancient Synagogues.” Art and Architecture of the Synagogue in Late Antique Palestine: In the Shadow of the Church. Leiden: Brill, 106-40.

Origen. 1982. Homilies on Genesis and Exodus. Translated by Ronald E. Heine. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press.

Ramirez, Janina. 2009. “Sub culmine gazas: The Iconography of the Armarium on the Ezra Page of the Codex Amiatinus.” Gesta 48, no. 1: 1-18.

Robbins, Gregory Allen. 1993. “Eusebius’ Lexicon of ‘Canonicity.’” Studia Patristica 25: 134-141.

Roberts, C.H. and T.C. Skeat. 1983. The Birth of the Codex. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skeat, Theodore Skeat. 1999. “The Codex Sinaiticus, The Codex Vaticanus, and Constantine.” Journal of Theological Studies 50, no. 2 (October): 583-625.

Weinberger, David. 2007. Everything Is Miscellaneous. New York: Times Books.

Endnotes

1 Canon, from the Greek κανών, literally a measuring rod, here refers to scriptural texts authorized for use within the church for worship and instruction.

2 The early Christian adoption of and preference for the codex book form has been treated extensively. See especially Roberts and Skeat 1983, Gamble 1995, and Hurtado 2006.

3 Whole Bibles in multi-volume format would still be costly to produce. However, owing to the reduced size and weight of each volume, they would be more serviceable for the range of required uses in the church compared to a single-volume Bible.

4 Of course, fixing contents in this way can also be a weakness. All decisions regarding included content and arrangement must be made in advance. Once bound, significant changes are impossible without deconstructing the codex and its binding. Then again, this is the point, and it underscores for us the physical nature of the canonization process.

5 Eusebius’s preference for the term κατάλογος over κανών for referring to the Bible makes sense of how the Eusebian canon tables were implemented and used.

6 Brakke suggests that in this letter Athanasius is not only setting up the boundary markers of orthodoxy but also shaping the nature of spiritual authority. He argues that Athanasius is trying to add spiritual and intellectual authority to bishops as opposed to academics.

7 It is also possible to work from a canon list to subsequently create or amend a physical collection—to move from the “second order” to the “first order.” For example, it is easy to imagine that Athanasius’ Easter Letter of 367 was received by church communities that may have lacked their own Bible collection, or they possessed an incomplete collection, or the collection they possessed included unauthorized texts. Based on the authority of Athanasius’s canon list, these communities may have been motivated to acquire, fill out, or correct their local Bible collection.

8 Richter contends that although chests—“a rectangular box with panelled sides … and horizontal lid, working on hinges [called a λάρναξ]”—were common in Ancient Greece, cupboards—quadrangular furniture with doors opening in front—were not known in Greece until Hellenistic and Roman times.

9 For excellent surveys of these developments, see Meyers 1997; 303-38, Hachlili 2000, 146-83; and Milson 2007, 106-40.

10 Fine collates the observations of scholars in noting that pictorial depictions of Torah Shrines from Palestine almost always show the doors of the armarium as closed (e.g., floor mosaic from the fourth-century synagogue at Hammat Tiberias), whereas depictions from the Jewish Diaspora typically show the doors as open with scrolls visible within (e.g., fourth-century Roman gold glasses).

11 Although originally written in Greek, no Greek manuscripts of Origen’s Homilies on Genesis survive except in fragments. This translation is based on the Latin translations of Rufinius of Aquileia (340-410).

12 The Codex Amiatinus (MS Amiatino 1) is located at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy, and is accessible in digital form at http://mss.bmlonline.it/s.aspx?Id=AWOS3h2-I1A4r7GxMdaR&c=Biblia%20Sacra.

13 We acknowledge that the setting for the cupboard miniature was likely a monastery library, not a church sacristy, as evidenced by Cassiordorus’ other comment in the Institutions (Book I.XIV.4) directing the monks to the Greek pandect located in the “eighth bookcase [armario].”

14 The First Bible of Charles the Bald (MS lat. 1) is located at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, and is accessible in digital form at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8455903b/f1.planchecontact.

15 Commenting on this point, Joachim Gaehde (1971, 395) notes that “[s]eparate evangelist portraits as frontispieces to each of the four Gospels are standard for Gospel Books but not Bibles. … [T]heir addition in the Bible of San Paolo to the evangelists on the Majesty page was most probably an innovation.”