Conversation Groups

Burnout Defined

Recognizing and Responding in Libraries

Abstract This article defines the three components of burnout recognized by the World Health Organization—exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficiency. Personal factors and workplace factors that research has shown to contribute to professional burnout are defined. Questions for personal reflection and discussion of one’s workplace are offered to identify propensity for burnout and to consider how to respond. Though burnout is often a systemic issue connected to workplace factors, suggestions for action and further reading are offered for those seeking ways to mitigate risk for burnout or to address an existing state of burnout.

Cultural Portrayal of Burnout

“Burnout” is increasingly examined in popular press, trade, and academic publications, and arguably defines the zeitgeist of contemporary culture and society. Visual portrayals of burnout often feature exhausted or harried-looking people, unable to function because of the condition (Image 1).

Image 1: Burnout at work — occupational burnout (Microbiz Mag. Wikimedia Commons).

Yet, manifestation of burnout may not be readily apparent as those experiencing symptoms often persist in fulfilling responsibilities of daily life. Journalist Anne Helen Peterson described this pattern in an essay for Buzzfeed, “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” noting, “Exhaustion means going to the point where you can’t go any further; burnout means reaching that point and pushing yourself to keep going, whether for days or weeks or years” (Peterson 2019). Peterson’s description may resonate with those who have experienced symptoms of burnout, but the World Health Organization’s definition, updated in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-11), provides a more quantitative examination.

Definition of Burnout

WHO’s definition of burnout, which is not classified as a medical condition, is included in Chapter 24 of the ICD-11, which details “Factors influencing health status or contact with health services” (World Health Organization 2019). The full definition appears as follows:

Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and reduced professional efficacy. Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life. (World Health Organization 2019)

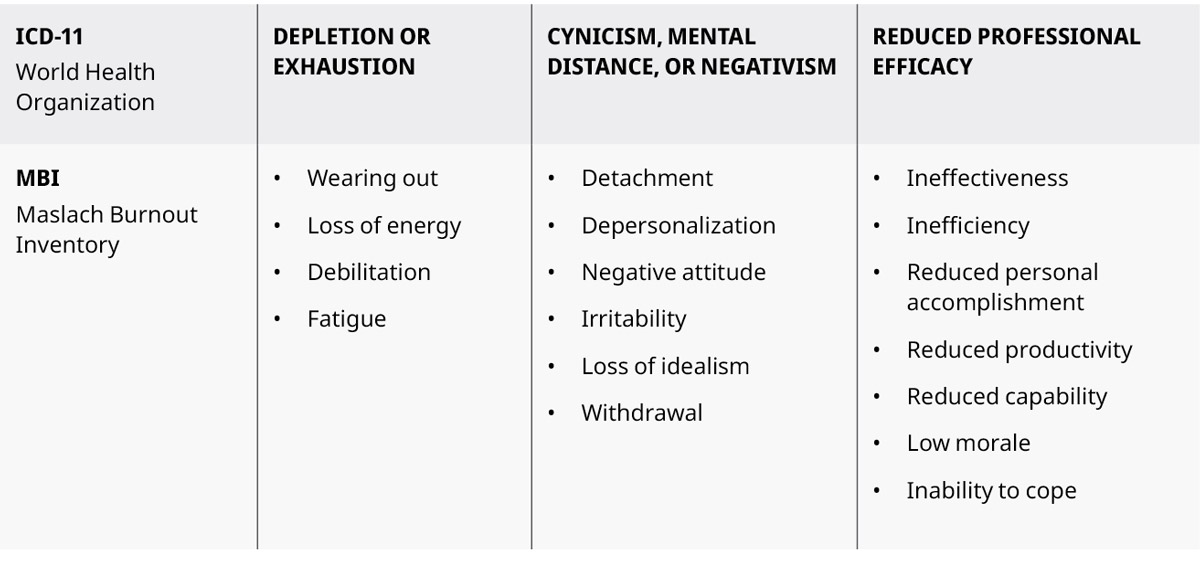

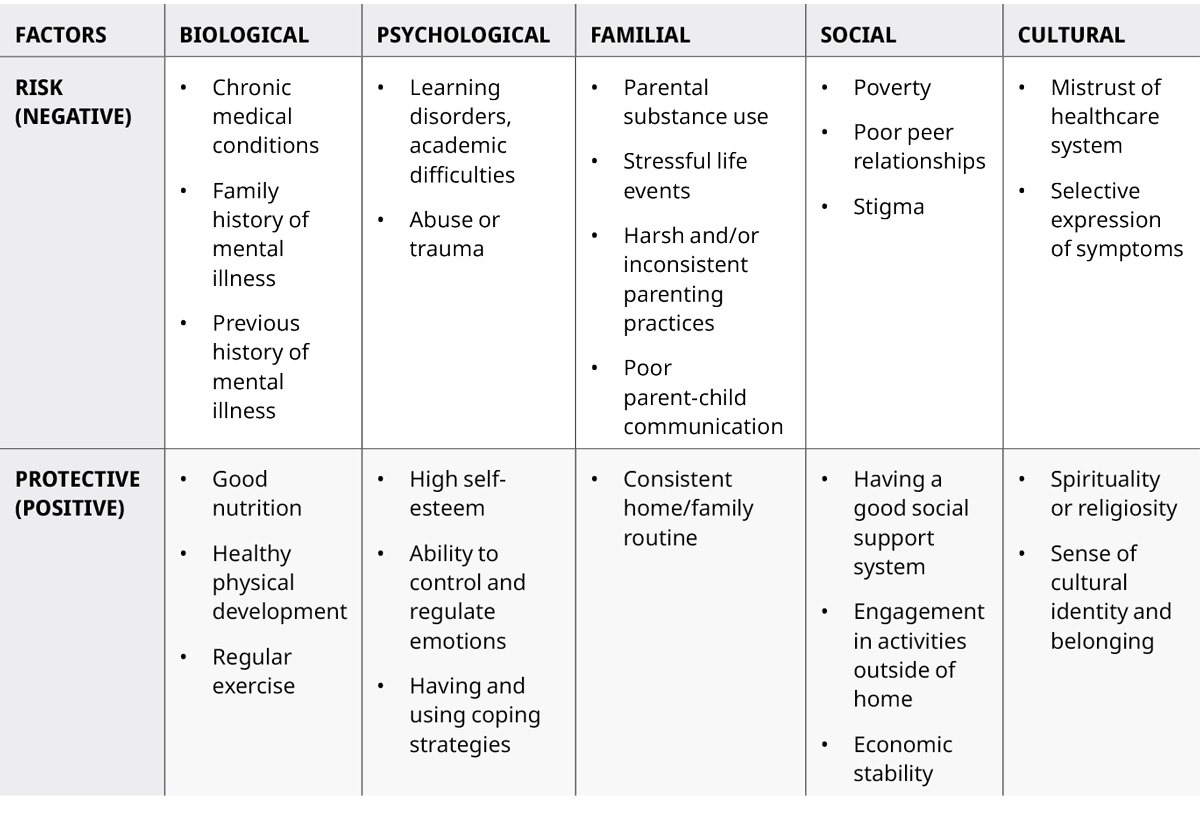

WHO’s definition is based on several decades of burnout research, with the three dimensions identified mirroring measurements from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). The MBI assessment was pioneered by Dr. Christina Maslach, an emeritus professor UC Berkley, and has emerged as the primary means for quantitatively measuring burnout (Mind Garden 2022). Maslach and fellow researchers, including Susan E. Jackson, Michael P. Leiter Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Richard L. Scwhab used additional synonyms in their research and assessment to describe the dimensions of burnout when developing the assessment. Such synonyms may be helpful to consider for those who may be afflicted by burnout but do not identify with the WHO terminology. The table below maps synonyms historically affiliated with burnout research to the current ICD-11 terms:

Table 1. ICD-11 burnout terminology and corresponding synonyms from the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Personal Factors

Although burnout presently manifests as a broad cultural reality, there are four personal factors that suggest greater likelihood of experiencing the syndrome, including occupation, personality, lived experience, and the unique capacity of an individual’s mind and body.

Occupation

Occupation is correlated with and may be predictive of propensity for burnout. Within the academic library profession, the issue of burnout went viral on social media as librarians widely shared cultural commentator Anne Helen Peterson’s Conference on Academic Library Management (CALM) keynote address, “The Librarians Are Not Okay.” Peterson’s powerful opening thesis asserted: “You [librarians] work passion jobs, and passion jobs are prime for exploitation” (Peterson 2022). Academic research broadly suggests that people working in helping professions are at greater risk for burnout (Yussuf 2020). The scope of present occupational burnout research is revealed by basic keyword database searching. Hundreds of academic journal articles widely document high rates of burnout among a variety of helping professions, including librarians, physicians, nurses, first responders, educators, lawyers, clergy, and social workers.

Personality

Similarly, personality has been shown to correlate with burnout prevalence. Arguably, one’s chosen occupation serves as visible evidence of a personal ethic and vocational desire to serve others. This assertion is supported by Fobazi Ettarh’s 2018 article, “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves,” which highlighted a survey showing 95 percent of librarians surveyed indicated that the “service orientation” had been a motivating factor in selecting the profession (Ettarh 2018). Meanwhile, another study showed that librarians derived satisfaction from and thrived on “serving people” (Ettarh 2018). Aside from service ethic, research from psychiatry professor Gordon Parker of University of New South Whales School indicates, “Burnout is increased in those who are reliable, conscientious, and perfectionistic… it’s often a consequence because they keep on giving and giving. And they have great difficulty turning off work. They feel guilty if they don’t complete assignments and get tasks done” (Yusuff 2020). Forbes similarly outlines greater tendency for burnout among three personality types in the workplace. First, the “workaholic” is performance-oriented and unable to balance work-life integration, making them prone to neglect self-care and becoming worn out (Montanez, 2019). Next, to keep other people, especially managers or leaders, happy, a “people pleaser” can become overextended. Finally, a “perfectionist” is prone to burnout on account of constant striving for high-performance standards paired with critical self-evaluation and concerns about the appraisal of others.

Life Experience

Lived experience can further predispose burnout tendencies based on personal history, sense of identity, and culture. Peterson, whose aforementioned CALM keynote received wide attention within librarianship, initially addressed burnout in a 2019 think-piece for Buzzfeed entitled “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation.” In the piece, Peterson described her experience with burnout and sagely asserted, “Burnout and the behaviors and weight that accompany it aren’t, in fact, something we can cure by going on vacation. It’s not limited to workers in acutely high-stress environments. And it’s not a temporary affliction: it’s the millennial condition. It’s our base temperature. It’s our background music. It’s the way things are. It’s our lives” (Peterson 2019). In 2020, Peterson further expanded upon her essay with Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation, a book which outlines the impact of cultural shifts and contemporary economic pressures that perpetuate unhealthy and unsustainable patterns in work, parenting, and socialization. Although Peterson’s writing centers on her experience as a millennial, evidence presented is common to many in older and younger generations who are caught up in the same zeitgeist.

Mind and Body

Finally, likelihood of burnout is influenced by the capacity of an individual’s mental and physical health. Although symptoms of burnout are often thought of as primarily mental and emotional manifestations, physical symptoms can also draw focused attention to the syndrome. Burnout registers in the body as stress, activating higher levels of stress hormones that can cause harm when remaining elevated over extended periods of time, according to stress researcher Dr. Jeanette M. Bennett from the University of North Carolina (Moyer 2022). A person’s coping mechanisms and unique tolerance for stress can influence biological and emotional responses to feelings of burnout. Moreover, the range of symptoms associated with the syndrome can vary, as noted in a recent New York Times article that listed insomnia, physical exhaustion, changes in eating habits, headaches, stomachaches, nausea, indigestion, and shortness of breath as symptoms to watch for (Moyer 2022).

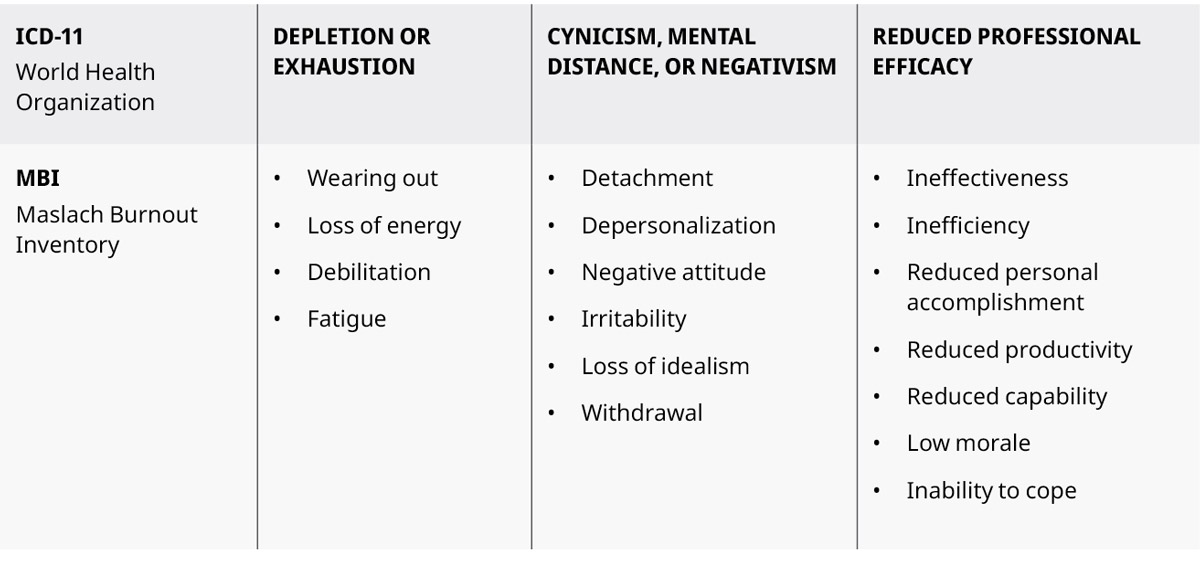

Just as a wide range of symptoms can serve as an indicator of burnout, it is also wise to consider lived experience in tandem with biology to better understand how one might be predisposed to burnout or other mental health challenges. The National Council for Mental Wellbeing identifies personal risk factors and protective factors for mental health challenges in their Mental Health First Aid training course. Factors can intersect and build upon one another and are shown with examples of negative (risk) and positive (protective) factors (National Council for Mental Wellbeing 2022).

Table 2. Risk factors for mental health challenges identified by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing

Workplace Factors

Although personal factors can profoundly influence one’s propensity for and degree of burnout, the root cause of the syndrome is increasingly recognized as a systemic issue connected to organizational factors that have been identified by research. In the Harvard Business Review, journalist Jennifer Moss captured this growing sentiment in a 2019, writing:

We tend to think of burnout as an individual problem, solvable by “learning to say no,” more yoga, better breathing techniques, practicing resilience—the self-help list goes on. But evidence is mounting that applying personal, band-aid solutions to an epic and rapidly evolving workplace phenomenon may be harming, not helping, the battle. With “burnout” now officially recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO), the responsibility for managing it has shifted away from the individual and towards the organization. (Moss 2019)

Moss supports her assertion further, citing a recent Gallup poll of 7,500 full-time employees that identified the top five reasons for burnout as: (1) unfair treatment at work, (2) unmanageable workload, (3) lack of role clarity, (4) lack of communication and support from management, and (5) unreasonable time pressure (Moss 2019).

The Gallup poll hints at six key contributing domains of burnout identified by research over the last two decades and across various countries: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values. Workload that leads to burnout is marked by little or no opportunity to rest, recover, and restore balance (Maslach and Leiter 2016, 105). In contrast, a sustainable or manageable workload allows an employee to use and refine their skills while also finding time to learn and become effective at new activities. Control, the capacity to influence decisions affecting work, gives employees a sense of autonomy and promotes healthy engagement on the job; whereas an environment in which an employee feels little or no control contributes to burnout. Rewards, material or intrinsic reinforcements, have the power to shape employee behavior (Moss, 2019). Insufficient reward or motivators—whether financial, institutional, or social—increases workers’ vulnerability for burnout because they can experience a sense of inefficiency and feelings of devaluation (Maslach and Leiter 2016, 105). Community involves on-the-job relationships, and risk for burnout is high when relationships are characterized by a lack of support, incivility, and administrative hassles (Valcour 2018). Fairness is defined as “the extent to which decisions at work are perceived as being fair and equitable” and can be based on personal treatment, observations of others, and policies (Maslach and Leiter 2016, 105). Finally, values are the ideals and motivations that attract people to a particular job or workplace (Maslach and Leiter 2016, 105). When there is a mismatch between individual and organizational values, an employee is more likely to experience burnout.

In the CALM keynote address, Anne Helen Peterson addressed many of these factors and then implored librarians to respond to systemic pressures in solidarity through implementing “guardrails” (Peterson 2022). Her eloquent call to action and explanation stated:

Guardrails stand in opposition to what’s often referred to as boundaries. Boundaries, particularly when it comes to work, are easily compromised. Boundaries are the responsibility of the worker to maintain, and when they fall apart, that was the worker’s own failing. In fact, breaking informal boundaries—like when work stops and starts—are often a way for people to evidence their commitment to the job itself. Boundaries, at least in the way we’ve come to understand them in phrases like “work-life balance,” are bullshit.

But guardrails? They’re structural. They’re fundamental to the organization’s operation, and the onus for maintaining them is not on the individual, but the group as a whole. They’re not just what the organization says it values are, but what it values in practice—and they’re modeled from the top echelons of leadership all the way down to the newest and most junior hires. (Peterson 2022)

Responding to Burnout: Reflect

Spending time in reflective conversation with a trusted confidant or journaling can provide a helpful starting point for recognizing and responding to personal and workplace factors. Recognizing that people who work in helping professions tend to experience burnout, first consider how your occupation defines or shapes your identity. Specifically, to what extent does your work define your identity? When one’s occupation is a primary descriptor of the way one exists in or relates to the world, acknowledging burnout and seeking recovery may be more difficult as the process potentially introduces a need to fundamentally redefine one’s sense of self or reorder priorities. Additional questions for reflection are introduced in a Harvard Business Review by Monique Valcour, an executive coach and professor who drew on her own burnout experience:

- Does your job/employer enable you to be the best version of yourself?

- How well does your job/employer align with your values and interests?

- What does your future look like in your job/organization?

- What is burnout costing you? (Valcour 2018)

Since burnout is not simply an individual syndrome, but rather a systemic issue, the following adapted versions of the questions above are designed to frame critical examination of an organization or workgroup.

- Do you observe burnout in your library? In the broader institution? If so, which of the three dimensions are manifest? How/when do you notice them?

- Does your library/university enable staff to be the best versions of themselves?

- How well does the work your library is asked to do align with the stated mission? Does there need to be a revision of the mission or values?

- What is the standing of the library? What does its future look like for your library in the broader organization?

- What is vocational awe costing your library? What hidden labor can you (or your leadership) better strive to make visible? When can your library say no?

An individual’s state of burnout may be implicated by a mix of personal and organization factors that necessitate a range of responses or actions depending on the extent to which agency can be exerted. Individuals may be able to modify personal practices or seek more sustainable workplace circumstances through candid conversations with a supervisor or supportive human resources representative. Yet, if these steps prove inadequate and organizational burnout factors go unchecked, employees may eventually leave a job or organization.

For those who desire additional support and need further resources to clarify ways for recognizing or responding to burnout, consider one or more of the following action steps.

Responding to Burnout: Five Action Steps to Consider

Professional Support

Seek counseling, therapy, or visit a doctor. Confidential conversation with a professional may help give voice to ideas that feel intimidating, scary, or unsafe to acknowledge to a friend, spouse, or coworker. Seeking support from a physician or other trained healthcare provider can identify a mental health challenge, such as depression—which studies have revealed can correlate with burnout (Maslach 2016, 108). Through dialog with trained professionals, one can sort through feelings more effectively to identify appropriate responses to feelings of burnout treatments for underlying medical issues that may contribute.

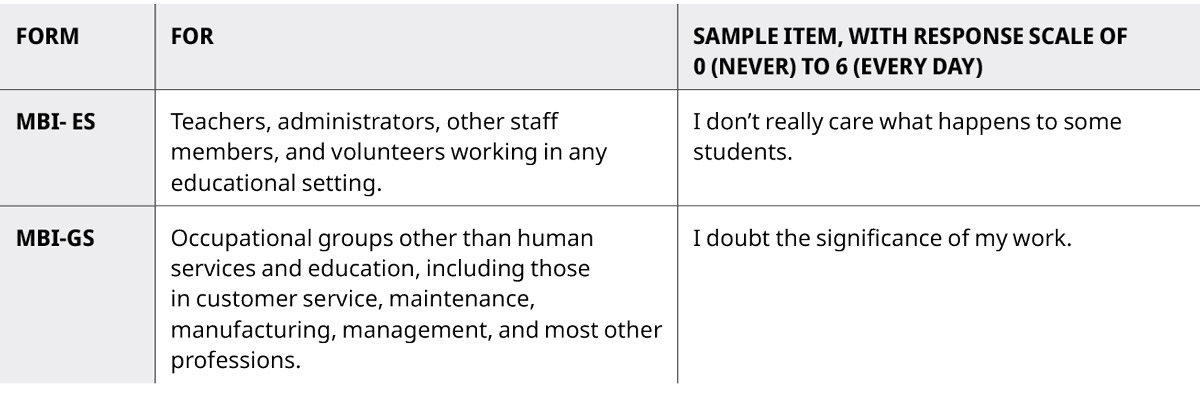

Maslach Burnout Inventory

The Maslach Burnout Inventory is available online via international publisher Mind Garden’s website. The paid online assessment has several versions designed for varied occupations. An excerpt of two MBI versions detailed on the Mind Garden site that may be relevant for those working in an academic or theological library are shown below.

Table 3. MBI forms appropriate for burnout assessment of academic and theological library staff members (Mind Garden 2022).

Paid MBI access (approximately $20 USD) provides users with a series of questions that are assessed and compiled in an individualized report. The report is automatically sent to the email registered when paying for site access, and a login is also provided so that users can retain access and download the report in perpetuity. The approximately 16-page individualized report generated describes degrees of burnout, identifies a profile that matches one’s results, provides stress reduction suggestions, and offers guidance to address burnout. The report is intended to aid interpretation of assessment results, but it is not a substitute for a diagnostic tool or care from trained healthcare providers (Mind Garden 2022). However, the assessment might provide helpful language for fostering dialog with a counselor or physician.

Widen Your “Window of Tolerance”

Dr. Elizabeth Stanley has crafted a 496-page book that examines contemporary cultural tendency to minimize stress, which results in short-circuiting the ability of one’s body to adequately recover. Expanding upon the research of renowned psychiatrist Bessel Van Der Kolk, Stanley provides an overview of research on stress and trauma while interweaving her personal narrative and motivation for undertaking this work. Her book provides readers with information and strategies to support recovery from traumatic experiences to improve performance and foster future thriving. Alternatively, for those unable to undertake Stanley’s hefty tome due to time constraints, a YouTube search for “Widen the Window” and “Talks at Google” will yield a 50-minute interview with the author that provides highlights of her important work.

Reflect on the Role of Work in Your Life

Jonathan Malesic, a former tenured theology professor, left his full-time teaching job because of burnout. In the years since, Malesic dedicated himself to writing The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives. This book shares Malesic’s personal reflections, unpacks research on burnout, and offers thoughts on how our identities and sense of value are shaped by the work we do. Malesic closes the book by exploring alternative communities and methods for centering our lives and defining meaning/value of an individual. This book is an accessible read for anyone struggling with burnout, but it is especially well suited for academics and those for whom theology holds meaning as part of their work.

Develop Rhythms of Rest

The practice of Sabbath, one day of rest reserved from conducting work, is held sacred in the Jewish tradition as well as some sects of Christianity. To guard against or recover from burnout, setting this or other similar rhythms of rest are essential.

For those seeking simple, straightforward ways of scheduling rest and recovery, the 3M framework, composed of macro, meso, and micro breaks might be a helpful place to start. Physician and life coach Salima Shamji describes the three breaks in her blog post “Immunize Yourself against Burnout.” Macro breaks are scheduled for a half or a full day once a month and are designed to let you brain “unwind and have some fun” (Shamji 2021). Meso breaks are smaller one- or two-hour periods each week that help your brain recharge, and for those who work indoors, Shamji encourages embracing activities outdoors for a change of pace (Shamji 2021). Finally, micro breaks are daily moments scattered throughout each day to check in with one’s body and emotions (Shamji 2021). Each of these break periods can help bring greater awareness of one’s physical and emotional needs rather than sustaining unhealthy momentum that can lead or contribute to burnout.

Mindfulness practices can be incorporated into micro breaks or embraced through more extended practices such as meditation or yoga. If these practices feel untenable due to lack of structure, physical limitations, or excessive stress, Elizabeth Stanley’s research outlines steps for Mindfulness-based Mind Fitness Training (MMFT) to help cultivate similar attentional control through prescribed steps designed to build resilience (Stanley 2019, 55).

For those who seek a theologically affiliated form of mindfulness practice, the Daily Examen, introduced by Saint Ignatius Loyola, offers a contemplative prayer composed of five movements intended to find evidence of God in of one’s day (Jesuits, n.d.). The five movements of the Daily Examen include:

- Cultivating awareness of God’s presence and offering gratitude for the day.

- Petitioning God for grace and wisdom to see the day as He sees it.

- Reviewing the day and focusing on specific moments and feelings that come to mind.

- Reflecting on how one drew near to or felt far from God in thoughts, deeds, and words.

- Looking ahead and thinking about how one can draw nearer to God, living out His plan and purpose in the hours or days to come.

Works Cited

Ettarh, Fobazi. 2018. “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. January 10, 2018. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/.

Jesuits. n.d. “How to Pray the Examen.” The Ignatian Examen. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.jesuits.org/spirituality/the-ignatian-examen/.

World Health Organization. 2019. “QD85 Burnout.” ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f129180281.

Malesic, Jonathan. 2022. The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives. Oakland, CA: University of California.

Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. 2016. “Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and Its Implications for Psychiatry.” World Psychiatry 15 (2): 103–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311.

Mind Garden. 2022. “Maslach Burnout Inventory.” Mind Garden. Accessed May 16, 2022. https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi.

Moss, Jennifer. 2019. “Burnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your People.” Harvard Business Review. December 11, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://hbr.org/2019/12/burnout-is-about-your-workplace-not-your-people.

Moyer, Melinda Wenner. 2022. “Your Body Knows You’re Burned Out.” New York Times. February 15, 2022. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/15/well/live/burnout-work-stress.html.

National Council for Mental Wellbeing. 2022. “Mental Health First Aid. 2020.” Washington, DC: National Council for Mental Wellbeing.

Peterson, Anne Helen. 2019. “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation.” Buzzfeed. January 5, 2019. Accessed June 13. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/annehelenpetersen/millennials-burnout-generation-debt-work.

———. 2020. Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

———. 2022. “The Librarians Are Not Okay.” Culture Study (blog). May 1, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://annehelen.substack.com/p/the-librarians-are-not-okay.

Shamji, Salima. 2021. “Immunize Yourself Against Burnout!” Salima Shamji (blog). September 30, 2021. Accessed May 9, 2022. https://www.salimashamji.com/blog/2018/7/20/blog-template-7l6yl-gz2wh-hrw5k-rcdp7.

Stanley, Elizabeth. 2019. Widen the Window: Training Your Brain and Body to Thrive During Stress and Recover from Trauma. New York: Avery.

Valcour, Monique. 2018. “When Burnout Is a Sign You Should Leave Your Job.” Harvard Business Review. January, 25, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://hbr.org/2018/01/when-burnout-is-a-sign-you-should-leave-your-job.

Yussuf, Ahmed. 2020. “Australian Study Shows Some Personality Types More at Risk of Burnout.” April 30, 2020. SBS News. Accessed May 18, 2022. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/article/australian-study-shows-some-personality-types-more-at-risk-of-burnout/iako3wwkh.