Creating a Digital Film Archive

Abstract Hasidic Jews came to the United States in significant numbers after the Holocaust, and a large percentage of them settled in Brooklyn, New York. The Hasidim are distinct from other New Yorkers, and from other Jews, in their old-world manner of dress, their customs, and lifestyle. Filmmakers Oren Rudavsky and Menachem Daum were granted extraordinary access to this community, to document their lives and share who they are with the world. From this access came the landmark documentary A Life Apart: Hasidism in America. The unused footage from the filming, a potentially rich resource for scholars, was inaccessible due to formats and lack of organization until Brooklyn College obtained an NHPRC grant to digitize and make it available to the public. The footage was opened to the public at the end of November 2022.

This paper will illustrate how the Archives at Brooklyn College resolved the problem of providing patron access to an undigitized film collection when we had no equipment for viewing, and neither expertise nor institutional funds for digitization. Before I discuss the project, a little background information will be useful.

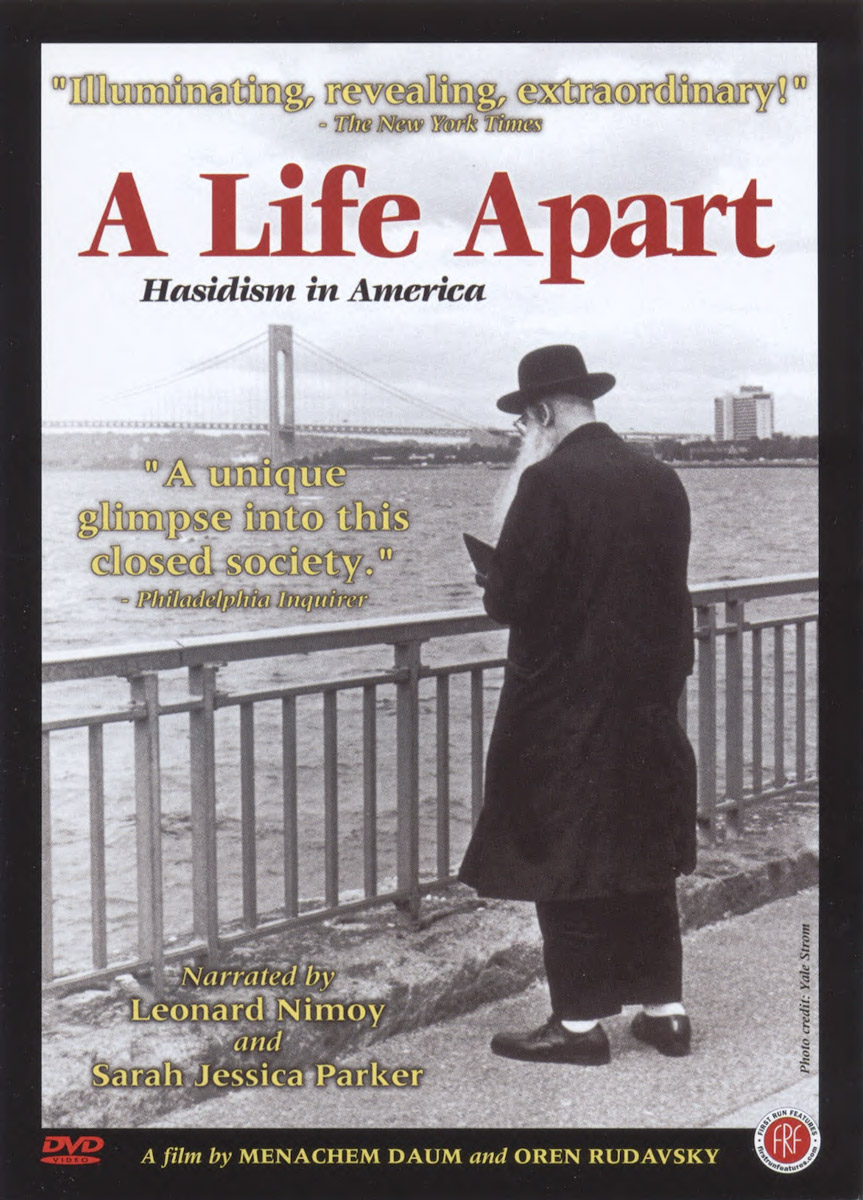

In 1996, filmmakers Menachem Daum (whose father was a member of the Hasidic community) and Oren Rudavsky released their NEH-funded documentary, A Life Apart: Hasidism in America (see image 1). Approximately 97 minutes long, the film examines the lives and culture of America’s Hasidic Jews, the majority of whom live in Brooklyn, New York. Although their decades of living in New York after surviving the Holocaust has changed their community to some extent, the Hasidim do live largely apart from mainstream America, not least through their mode of dress, language, and customs.

Image 1: Cover for DVD version of A Life Apart: Hasidism in America. Photo by Yale Strom. Poster design Joe Sweet. Courtesy of Menemsha Films.

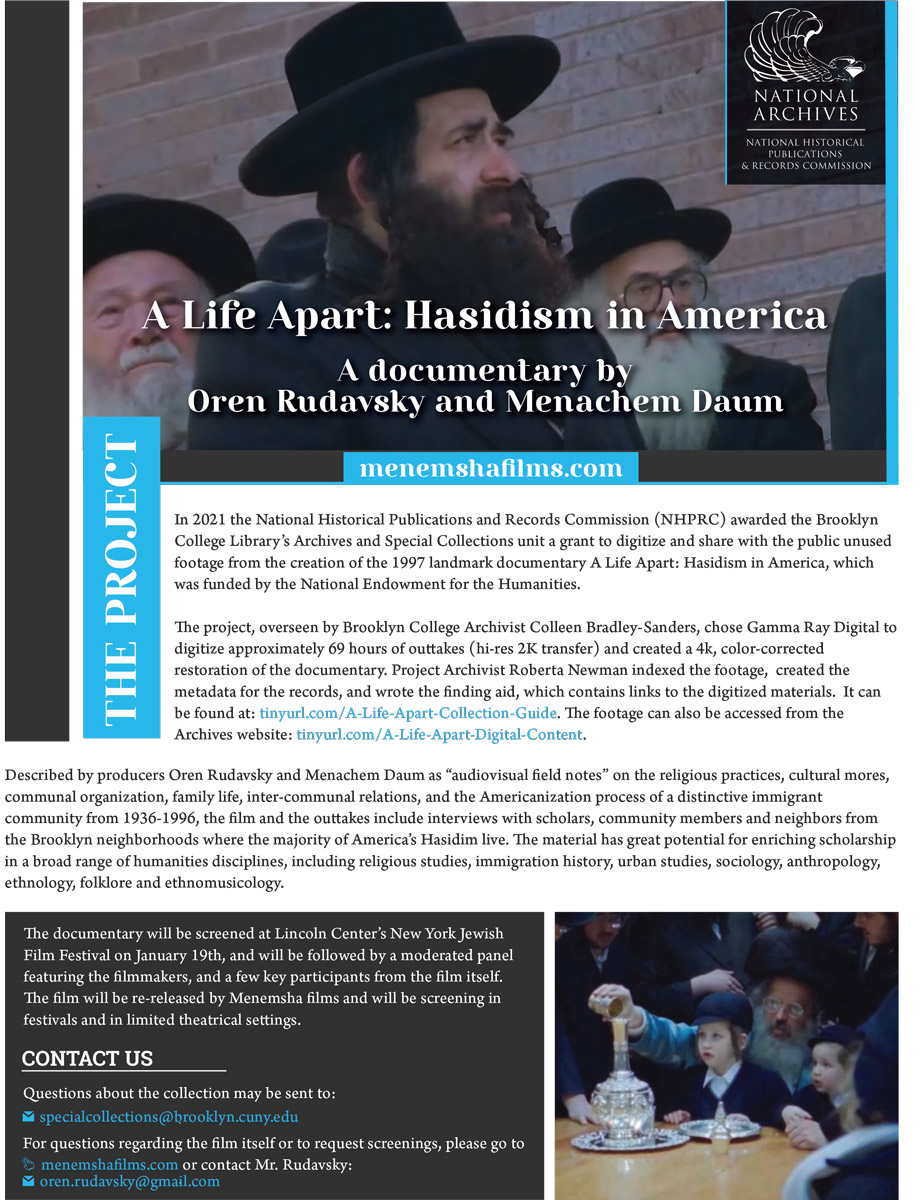

The film, as well as the archive of more extensive and widely varied footage that did not make it into the final cut, explores the Hasidim sense of self and their interactions with ever-expanding circles of larger communities and spheres, including their families; their courts, the community of all Hasidic courts; other American Jews; and their non-Jewish neighbors, politics, and the economy (see image 2).

Image: 2 Young Hasidic boy learning the aleph-beit. Photo by Oren Rudavsky.

The film footage and sound recordings, in a variety of formats, were donated by the filmmakers to Brooklyn College in 2012. In early 2020, not long before Brooklyn College shut down due to COVID, Rudavsky and Daum contacted me to discuss the possibility of digitizing the materials and making them available to the public.

The materials in this particular collection included ¾-inch tapes (which hold the audio tracks with low resolution images) and 16mm film reels. Because it consisted of formats to which we could not provide access, it was unprocessed. Labels were sometimes incomplete and confusing. Getting outside funding for the digitization project was the only way this collection could be opened to the public.

Fortunately, the producers were deeply involved in the project. They were invaluable not only for their knowledge and ability to be a liaison with the vendor, and consultants for the project archivist, but also for making sense of the physical collection in the Archives and determining exactly which materials were required for the digitization project.

Our first grant application, to the National Film Preservation Foundation, was unsuccessful, largely because their guidelines for what a grant would pay for were misleading, and our proposal did not actually qualify.

Over the course of the next year and a half, primarily working remotely, we also sought money from the NEH, and from the NEA (twice). All the applications were unsuccessful. The NEH application was the most challenging and frustrating, even with the help of a woman who’d both written and reviewed NEH grant proposals. I think our plans were perhaps too ambitious and not as well thought-out as they should have been.

I should add here that the various applications were not identical projects, largely due to varying amounts of funding available from the different granting entities. We wanted to get the funding any way we could, whether that meant a single grant or multiple grants and a project done in stages.

In the end, we were successful with a grant application to the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), and in 2021 we were granted $150,000 for our one-year project. With some aspects of the project slowed down by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., campus access, people getting sick, etc.), we requested a three-month extension, and made the project public at the end of November 2022.

What was the Project?

Our proposal to the NHPRC was to digitize just over 69 hours of footage that was not included in the documentary, hire a project archivist to organize the digitized film segments, and create metadata records for each of them. Why do it at this time, over 20 years after the film debuted, and what made it worthy of a grant?

Mr. Rudavsky and Mr. Daum felt strongly that the unused footage contained material that would be of interest to researchers. In our grant application, we noted that there is interest in the Hasidim, demonstrated by the popularity of memoirs from young former Hasidim who chose to leave their communities, such as Deborah Feldman’s 2012 memoir, Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots, which was the basis for a four-part miniseries on Netflix in 2020.

Digitizing the footage made it available to the public for the first time, and no comparable audio-visual collection on the Hasidim exists.

The archive contains original primary sources for scholars and the general public, including:

- Oral histories with members of the Hasidic community, including two former Hasidim who have opted out of the community.

- Community scenes with leaders of six Brooklyn Hasidic dynasties: Bobov, Ger, Munkac, Satmar, Lubavitch, and Viznitz.

- Intimate scenes of Hasidic family life.

- Events such as weddings, holiday celebrations, Holocaust commemorations, and more.

- Post-Soviet spiritual pilgrimages by Hasidim to venerated sites in Eastern Europe, as well as Hasidic missionary activities among Jewish communities in former Soviet countries.

- Interactions between Hasidim and other residents of Brooklyn,in Prospect Park and elsewhere.

- Interviews with scholars, including Arthur Herzberg, Yaffa Eliach, Samuel Heilman, Martin Marty, Anne Braude, Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, and David Fishman.

Brooklyn College currently uses Illumira for hosting its digital content. I said “currently uses,” because for the past year, I’ve been told that the college is moving to a new platform called Yuja. I have not yet had a single conversation about the migration of our existing digital collections, nor any training on the new platform. In addition, the College has had access to JSTOR Forum for a while, and I recently learned there is a new partnership with ITHAKA which will allow us to not only publish and manage our digital collections on JSTOR but will also add the digital preservation of collections through a service called Portico. In addition, JSTOR is apparently working on giving users the capability of posting audio and video collections. It would certainly make our life easier to have all our digital materials in one place, rather than split between Yuja and JSTOR. I believe our agreement officially begins in September, so I haven’t explored any of this yet.

In July 2021, we transferred all the materials to be digitized to the vendor, who was located in New York City and happened to be the firm that worked on the production of the original documentary. The grant was supposed to officially start on September 1. On August 25, the vendor sent out a press announcement about the closure of its media services operations and its plans to focus on their real estate holdings. They did not contact us, we had to reach out to them to confirm the closure and their inability to do the work they’d agreed to do.

We had to scramble to find another vendor on very short notice. Fortunately, as part of the grant application process, we had researched a couple of other vendors, one in Los Angeles, California, and one in Boston, Massachusetts. We didn’t choose the one in Los Angeles because it couldn’t do everything that we wanted, and the Boston firm initially didn’t respond to our request for a quote. When we had to scramble after our first choice backed out, we contacted the Massachusetts firm again. Mr. Rudavsky had worked with Gamma Ray Digital in the past, and when we were desperate for a vendor in August 2021, they responded, and we could not have been happier with their work and customer service. In addition to digitizing all the outtakes, Gamma Ray Digital also provided the Archives with a new digital and color-corrected copy of the documentary.

The digitization alone would have cost us almost $146,000 of our $150,000 grant, if the vendor had not given us a significant discount that enabled us to stay within the limits of the grant and have money for the project archivist, among other things. The discount, along with in-kind contributions of time and expertise from the filmmakers, helped cover about half of the cost-share requirement. The NHPRC requires a 25% cost share with their grants. Table 1 shows part of the project quote from Gamma Ray Digital and is shown primarily to demonstrate that there were many steps to the process.

|

Description |

Qty |

Rate |

Cost |

|

Evaluate & Prepare (if necessary) 168 lab rolls of 16mm color negative, estimated at 800 feet each |

40 |

$35.00 |

$1,400.00 |

|

Clean S16mm color negative |

141,312 |

$0.10 |

$14,131.20 |

|

Scan S16mm color negative outtakes and A/B roll feature film at 2K to flat ProRes 4444 files. Includes ProRes Proxy files with KeyKode Burn-in. Color correction of feature film |

141,312 |

$0.58 |

$81,960.96 |

|

Upload review files to Frame.io for approval |

168 |

$32.00 |

$5,376.00 |

|

Clean and Bake ¾” tapes (30 minute cassettes) |

180 |

$10.00 |

$1,800.00 |

|

Digitize ¾” tapes (30 minute cassettes) to mov files |

180 |

$90.00 |

$16,200.00 |

|

Pull up Digitized audio to 24fps Sync 75 hours of Audio to 62 hours Picture mov files |

150 |

$60.00 |

$9,000.00 |

|

Create 2k ProRes with sync sound for each lab roll |

168 |

$30.00 |

$5,040.00 |

|

Create mp4 from 2K ProRes |

168 |

$30.00 |

$5,040.00 |

|

Archive Synced ProRes files, MP4 files for archive to LTO-8 2 sets. Price includes data prep (Checksum verification to Library of Congress Bagit spec), human- readable PDF manifest, tape stock and tape writing/verification |

4 |

$550.00 |

$2,200.00 |

|

8 TB External Hard Drive for Pro Res and MP4 files |

2 |

$450.00 |

$900.00 |

|

Freight Shipping (NYC->BOS) |

2 |

$650.00 |

$1,300.00 |

|

Freight Shipping (BOS->NYC) |

2 |

$750.00 |

$1,500.00 |

|

SUBTOTAL |

$145,848.16 |

||

|

Cost Sharing/Discount |

1 |

$26,000.00 |

$26,000.00 |

|

TOTAL |

$119,848.16 |

TABLE 1 Partial image of vendor quote for project. Gamma Ray Digital (www.gammaraydigital.com)

I was extremely grateful to have the two producers working with me on this project, as I have almost no knowledge of filmmaking and the various steps that were part of the digitization process, especially the preparation. It would have been significantly more challenging to do without them, and I’m not sure I would have undertaken the project without their involvement.

Mr. Rudavsky worked closely with the vendor to ensure the work was done to our satisfaction, and actually handled the first step of the project himself, evaluating and preparing the 168 rolls of 16mm film negative, with the help of two assistants. The collection sat on the shelves in the archives from 2012 -2021, completely unorganized, exactly as the filmmakers had boxed it up for us.

This meant that before any digitization could take place, Mr. Rudavsky and his assistants had to sort through the disorder of the collection and splice film where sections had been removed for the documentary. The 16mm film had to match the ¾-inch tapes which had the audio but only low resolution non-archival quality images. But, before the ¾-inch tapes could digitized, they needed to be baked. That term confused me at first but some of you may be familiar with the phrase “sticky shed syndrome,” which is the deterioration of magnetic tape. Literally baking the tapes makes them playable again, at least long enough to get them digitized.

Some of the ¾-inch audio tapes were missing, but fortunately Mr. Daum had a Hi8 backup and some DAT tapes, which covered the missing audio.

The original film was digitized, and digital shots from this 16mm film were then replaced in the dailies from which they were originally taken. A 2K version of each of the 168 negative rolls was made, digitized, and synched with the audio. An MP4 version of each roll was then created for us to upload to Illumira, and a high resolution 4K version of the documentary was created and color-corrected.

Once the film was cleaned, repaired, digitized, and synched with the audio, we needed to organize those 69 hours of film. Our project archivist, Roberta Newman, had worked with the producers as a researcher during the making of the film, and so was familiar with the footage. She also served as the Director of Digital Initiatives for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research from 2013-2019, and so was well-qualified to do this work.

Ms. Newman worked over 300 hours to organize and catalog the film segments, creating metadata records for each one. She worked entirely remotely, using a collaboration software called frame.io. The vendor introduced us to frame.io, which provided a way for Mr. Rudavsky to check on the work being done, including color correction, audio synching, and noting any problems, such as gaps. At least once during the project he realized we were missing a tape and we searched through the archives to find it, and fortunately we did. Gamma Ray Digital uploaded low-resolution footage to frame.io, and using an individual account that Mr. Rudavsky opened (for low cost, maybe $20/month), Ms. Newman was able to organize the digitized film segments into series with varying numbers of individual segments. Frame.io allows users to make notes that are automatically time-coded to the footage and saved in a downloadable text file. The information in the text file was then easily transferred to an Excel spreadsheet Ms. Newman created for the metadata. She used this spreadsheet, which also included appropriate subject terms (using primarily Library of Congress Subject Headings), to create the records in Illumira. While Illumira was a pretty stable platform, she found it to be not very advanced for an image database, and also not very flexible. And this is one example of why we’re looking forward to moving to JSTOR Forum with our digital collections.

After Ms. Newman created the Illumira records, I uploaded the video files from the hard drive containing the MP4 files. Once this was done I checked each record to ensure all the necessary information was in place, and then made the records public. This is the Illumira site that hosts our digital collections: https://brooklyn.illumira.net/showcollection.php?pid=njcore:169222.

The collection is divided into a number of series (called sub-collections on Illumira). There are 18 altogether, and each series has varying numbers of film segments in it. The Schiller family has only five segments, while the Gold family has 18, and there are 17 scholar interview segments. There are 185 segments in total.

We had some extra money: digitization was slightly less than we expected, and we ended up not needing to pay for digital storage. The NHPRC allowed us to repurpose the money by adding a new performance objective to our original list of objectives, which was the creation of several short, edited segments that could be used by educators, scholars, etc. Oren Rudavsky took on the task of creating these short segments. One segment shows men baking matzoh (https://brooklyn.illumira.net/show.php?pid=njcore:197781), while another, which Mr. Rudavsky just recently shared, shows the dedication of a yeshiva (https://brooklyn.illumira.net/show.php?pid=njcore:199693).

You can see on the list of sub-collections one titled Ger Yeshiva in Brooklyn. Within this series are 11 film segments about the Ger Yeshiva. When we click on one of the segments, you can see the abstract, which shows how the project archivist used time codes to indicate changes in scene or action within the segment.

Promoting the Collection

Once you’ve created a digital collection, you want people to see it and use it. To that end, we sent the metadata to Atla, and the collection was added to the Atla Digital Library and is available at https://dl.atla.com/collections/a-life-apart-hasidism-in-america?locale=en.

We have been putting our finding aids into ArchivesSpace for a few years, and we created one for this collection. Our ArchivesSpace instance, which is hosted by Lyrasis, can be reached from both the Archives website and the CUNY Catalog, which automatically pulls our records from ArchivesSpace (https://archives.brooklyn.cuny.edu/repositories/2/resources/62).

Clicking on a series title reveals all the segments within a series, and once you click on an individual segment, you can connect to the actual video by clicking on the link under the Scope and Contents label on the left. Our page for digital collections offers links to the full collection on lllumira, and also the finding aid on ArchivesSpace (https://libguides.brooklyn.cuny.edu/c.php?g=1135687).

I mentioned the college’s new agreement for the use of JSTOR Forum. When telling people about the collection we try and direct them to our Archives page about the collection rather than directly to Illumira, since we’ve been told for over a year that we’re moving to a new platform, and we didn’t want to give people links that will become invalid.

The New York Jewish Film Festival is an annual multi-day event held at Lincoln Center every year in January, and the documentary originally premiered here, and this year the producers were able to get a screening of the newly digitized film on the schedule. In addition to talking about the archive in the post-screening panel discussion, we created a flyer for attendees, to let them know where they could find the archive.

Image 3: Flyer created for the 2023 New York Jewish Film Festival screening of the documentary

Since the screening, and promotion of the collection on H-net and Facebook, we’ve also heard about members of the Jewish community learning about the archive on Twitter. I’m not a Twitter user, but one of the producers mentioned in April that while at synagogue someone mentioned to him how grateful he and his friends were that the outtakes had been put online. Mr. Daum asked where the person had learned about the archive, and they responded, “from Twitter.” Apparently, there is at least one group on Twitter interested in Jewish-related topics, and word of our digital archive has appeared there.

Next Steps

Our next big task will be moving the digital archive from Illumira to JSTOR Forum, if their AV capability will be available reasonably soon, or to the other content host selected by the College library administration, Yuja.

For future outreach efforts, we plan to work with our new user experience librarian to come up with ways to promote the use of the collection inside and outside the college. Of course, it could be in use already, and we wouldn’t know since the platform is open to the public.

Longer term plans include Mr. Rudavsky creating some of those short segments from the scholar interviews that were unused in the documentary, and the filmmakers would like to hold a forum to show the material to the academic community and the public.