Primary Source Instruction in Theological Libraries through Rare Book Collections

Collaborative Initiative in Credit-Bearing Library Labs

Abstract This paper addresses how students perceive primary sources instruction in the credit-bearing information literacy labs and explores the implications of this pedagogical practice on the development of students’ understanding of research. Through collaboration with the course instructor, library labs instructor, and Chief Librarian, the students visited the Rare Book Room and interacted with the rare and unique material as part of their course curriculum. The authors completed a thematic analysis of students’ reflections, exploring the impact of this visit on their research journey and their perceptions of how primary source instruction has impacted their understanding of other topics covered in the course. The authors share their lessons learned and recommendations for those who would like to adopt a similar practice at their institutions.

Introduction: Study Background

The need for primary source instruction for undergraduate students is often an issue of contention. Some educators claim that undergraduate students are not prepared to interact with primary sources and need to engage with more pressing challenges, such as searching for relevant material in the library catalogue or understanding how to adhere to academic integrity regulations. However, this paper aims to challenge this notion by exploring the impact of primary source instruction on students’ learning. This paper will first discuss our research problem and research question, followed by a short literature review. Later we will explore the library labs’ delivery context and curriculum design. We will further highlight the main elements of the Rare Book Room visit provided to our students and present the findings of this study.

Primary source literacy can be challenging to define due to a variety of different methods that librarians or other educators might use to teach students about primary sources (Daines and Nimer 2015). However, one definition that provides a broad insight into primary source literacy comes from guidelines for primary source literacy developed by ACRL (2018). According to these guidelines, primary source literacy can be defined as “the combination of knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to effectively find, interpret, evaluate, and ethically use primary sources within specific disciplinary contexts, in order to create new knowledge or to revise existing understandings” (ACRL 2018, 2). This definition provides a comprehensive view on primary source literacy that applies to our research. According to Crisp (2017), primary source literacy is “a metaliteracy, incorporating elements of traditional information literacy, visual literacy, archival literacy, etc.” (8). This demonstrates the need for a wholesome approach to primary source literacy that considers all aspects of the information literacy (IL) curriculum and provides a contextual base for primary source literacy.

This research will answer the following research question: How can IL skills of undergraduate students improve through primary source education using rare book materials?

Literature review

New university students often have limited knowledge about the importance of primary sources for their research (Sutton and Knight 2006). According to Daines and Nimer (2015), many librarians focus in their instructions on how to “differentiate between types of sources, rather than teaching students about the access and use of these resources” (21). However, to be able to do it, librarians need to adopt a contextualized approach to IL education. Primary source education offers this opportunity since it is often cross-disciplinary and can be utilized in many contexts or subjects. It is essential for librarians to adopt a comprehensive approach to IL instruction that would benefit students’ long-term goals and should be centred in an understanding of the research process, rather than a simple demonstration of library tools (Hubbard and Lotts 2013). To be effective, IL should be integrated into the broader university curriculum and foster discipline-specific skills. Primary source literacy can promote this deeper learning of IL concepts through a contextual approach to IL (Daines and Nimer 2015).

Primary source literacy requires special skills that “both build on and differ from those learned through more traditional secondary source library research” (Archer, Hanlon, and Levine 2009, 411). Integration of primary source literacy into an IL curriculum offers a variety of benefits for students. First, it allows students to get “excited about research” (Craig and O’Sullivan 2022, 95). Second, primary source literacy promotes critical thinking (Malkmus 2007; Yakel 2004), increases students’ confidence (Hubbard and Lotts 2013), and promotes understanding of the research process (Jarosz and Kutay 2017). Third, it can also increase students’ engagement and “promote historical empathy” — something that is not widely discussed in the literature (Malkmus 2007, 39).

Furthermore, primary source education provides many collaborative opportunities between faculty members and librarians (Daines and Nimer 2015). Many faculty members highlighted that they appreciated the collaboration with librarians and identified the important role of information professionals in helping students to develop primary source literacy (Malkmus 2008). Daines and Nimer (2015) state that “coordination between librarians and faculty elsewhere in the university is critical for preventing instructional gaps when teaching information literacy skills — particularly in the context of primary sources” (22).

Considering the benefits of primary source literacy for students, as well as the collaborative opportunities it provides, the authors decided to implement primary source education in their information literacy library labs.

Delivery Context: Library Labs

To better understand the context in which the primary source instruction was delivered, it is vital to explore the background information about Saint Paul University (SPU) and the library labs. The university has approximately 884 FTE, with about 1,100 students (undergraduate and graduate) in four Faculties: Human Sciences, Theology, Philosophy, and Canon Law. The university is federated with the University of Ottawa, which is approximately 40 times larger than SPU. An officially bilingual university, SPU serves both English- and French-speaking students, who can submit their assignments in either language. SPU also has a diverse international population from over 25 countries; this accounts for approximately 20% of the student body. The university has approximately 125 professors (including sessionals) and three librarians. The library’s physical collection holds over 520,000 books; within those, over 11,000 books and works were produced between 1450 and 1800.

The current library labs are part of a mandatory undergraduate course, HTP1105, “Critical Analysis: Reading and Writing Academic Works.” These labs are the result of years of development. The process behind the library lab goes back to 2015 when a discussion happened between the Deans, higher administration, and the Chief Librarian. A need was identified to further help students with information and digital literacy. Based on those discussions, and with the support of the Deans and higher administration, the Chief Librarian proposed a library lab to focus on the ACRL Information Literacy Framework as its foundation in order to develop competencies found in the framework. An initial pilot was proposed in 2016, when the lab was offered as two 75-minute sessions for an optional 15 bonus points. These points would be added to the final grade if the student participated in all labs and submitted an assignment.

It was noted after reviewing the pilot term that only four students out of a possible 32 students had submitted an assignment and participated in the lab. So, in 2017, the lab was offered as two 75-minute sessions with a bonus of 25 points. Once the bonus points increased, more than half of the students participated and submitted an assignment. Then, in 2018, after a comprehensive course review and revamping of the HTP1105 course, the course and lab became mandatory for undergraduate students in Human Sciences, Theology, and Philosophy (HTP). At that point, the course was offered in both English and French by professors in one of the three faculties, and the lab was taught by a librarian. The library lab portion was modified to a 12-week, 12 hours lab requirement, with multiple assignments fully integrated within the scope of the course. The professor would have 75% of the final course grade, and librarians would have 25%. The course and lab are offered each fall semester at SPU.

In 2022, the librarian teaching the lab portion (Marta Samokishyn) proposed a new concept and was fully supported by the professor teaching HTP1105 (English version, Professor Richard Feist). The proposal included a visit to the Rare Book Room, with instruction and discovery of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources led by the Chief Librarian. The students could complete an additional lab assignment for bonus marks. Thematically, we noticed that when we offered extra incentives, students were more willing to participate and submit additional assignments.

Library Labs Curriculum Design

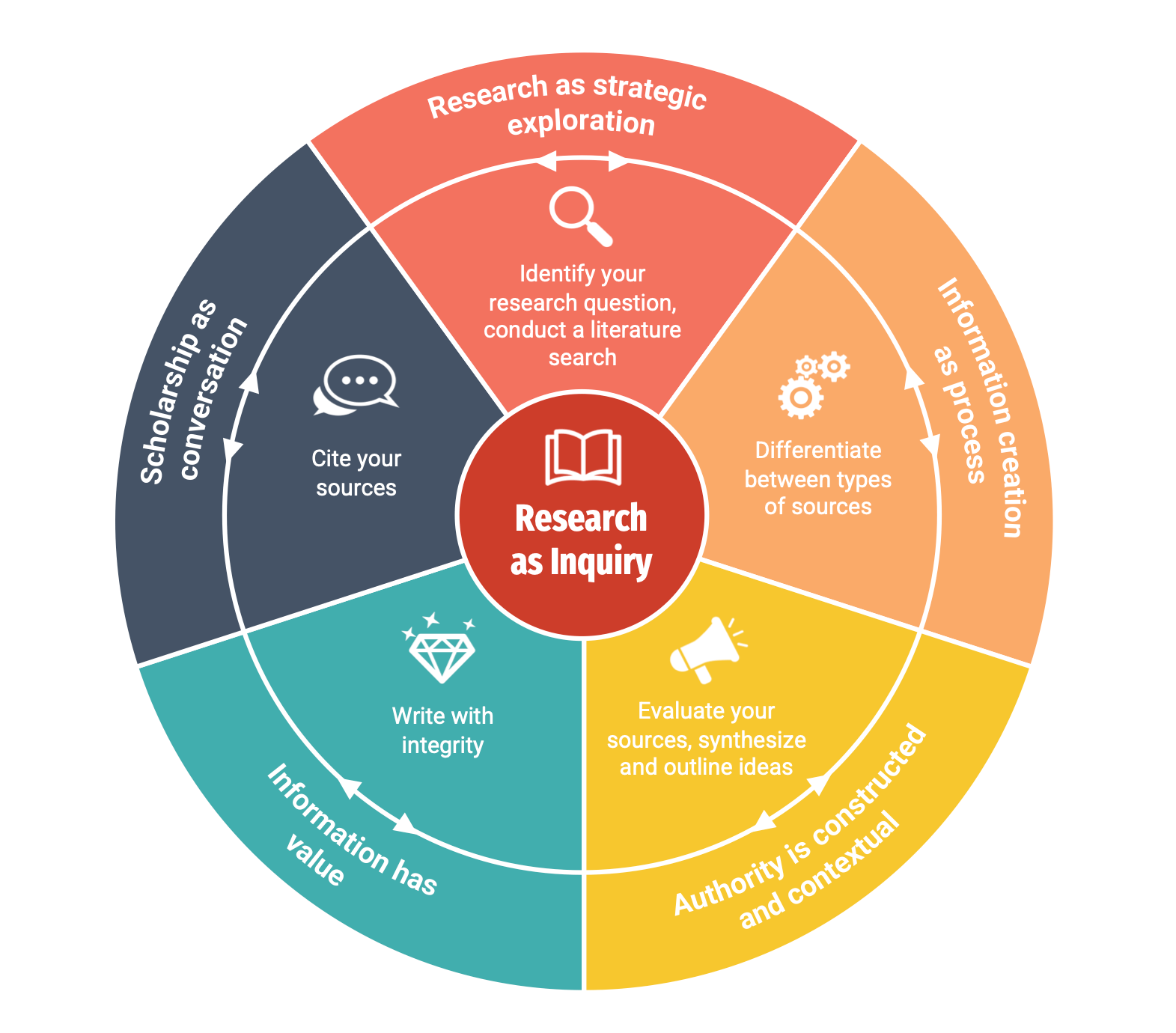

As previously noted, the library labs were aligned with the ACRL framework and used the frame “Research as Inquiry” and its central overarching theme (see figure 1). The labs were grounded in inquiry-based learning to foster students’ curiosity and engagement.

Figure 1 Alignment of the course modules with ACRL frames

Other modules of the labs focused on the following skills and ACRL frames:

- Module 1: Searching as Strategic Exploration (included information about the elements of the research process, question mapping, and basic and advanced search strategies). Students had to develop a research journal in this module (worth 20% of the final lab grade) with their search strategy and steps of the search process.

- Module 2: Information Creation as Process (included understanding the difference between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, as well as understanding how to read scholarly sources, and the peer-review process). During this module, a visit to the Rare Book Room at SPU was organized. Students were offered to complete an optional assignment in the form of a one- to two-page personal reflection about the impact of the visit to the Rare Book Room on their understanding of research. This assignment was worth five bonus lab points.

- Module 3: Authority is Constructed and Contextual (evaluation of sources based on the authority and ACT UP Framework). Students had to prepare a literature review matrix worth 25% of the lab grade, evaluating their five sources based on authority, currency, main arguments, etc.

- Module 4: Information has Value (focused on academic integrity and citation skills). Students had to develop an enhanced literature map (20% of the lab grade), where they synthesized main arguments from the previous assignment and provided some paraphrases and summaries with proper in-text citations and references.

- Module 5: Scholarship as Conversation (focused on academic writing skills, structure of an academic paragraph). Cumulative literature review assignment (30% of the grade) where they demonstrated all the skills acquired during the semester.

A version of this inquiry-based IL course as a full semester course is available as an open education resource through Ecampus Open Library (https://openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca/item-details/#/1e03382e-3d4d-4f9b-b8d4-8b5893e75812?) with the accompanying reading guide (https://openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca/item-details/#/efafb3af-566f-4aa3-bf5a-1f48b76fa181?). The course implemented an iterative research process and scaffolding in both formative and summative assessment so that students built on the foundational IL skills throughout the semester in preparation for their final deliverable: a small-scale literature review.

Virtual Visit to the Rare Book Room at SPU

The visit to the Rare Book Room was organized by the lab and course instructor during the course time and was led by the Chief Librarian in collaboration with the course instructor and lab instructor. It included a one-hour tour of the Rare Book Room, during which students had an opportunity to work directly with the rare books and other primary source materials (e.g., letters, manuscripts, facsimile editions, etc.). The following is a sample of resources that were presented to them:

- Thomas Aquinas, Catena aurea super quator Evangelistas, 1475; the oldest book in the collection

Image 1 Thomas Aquinas, Catena aurea super quator Evangelistas, 1475

In this book, students were instructed on early book printing (this book was printed during the first 30 years of the printing press in the Western World), shown early printing styles and stylization, discovered different binding practices, and learned about ink usage and various paper makeup (e.g., cotton rag paper as opposed to a modern pulp).

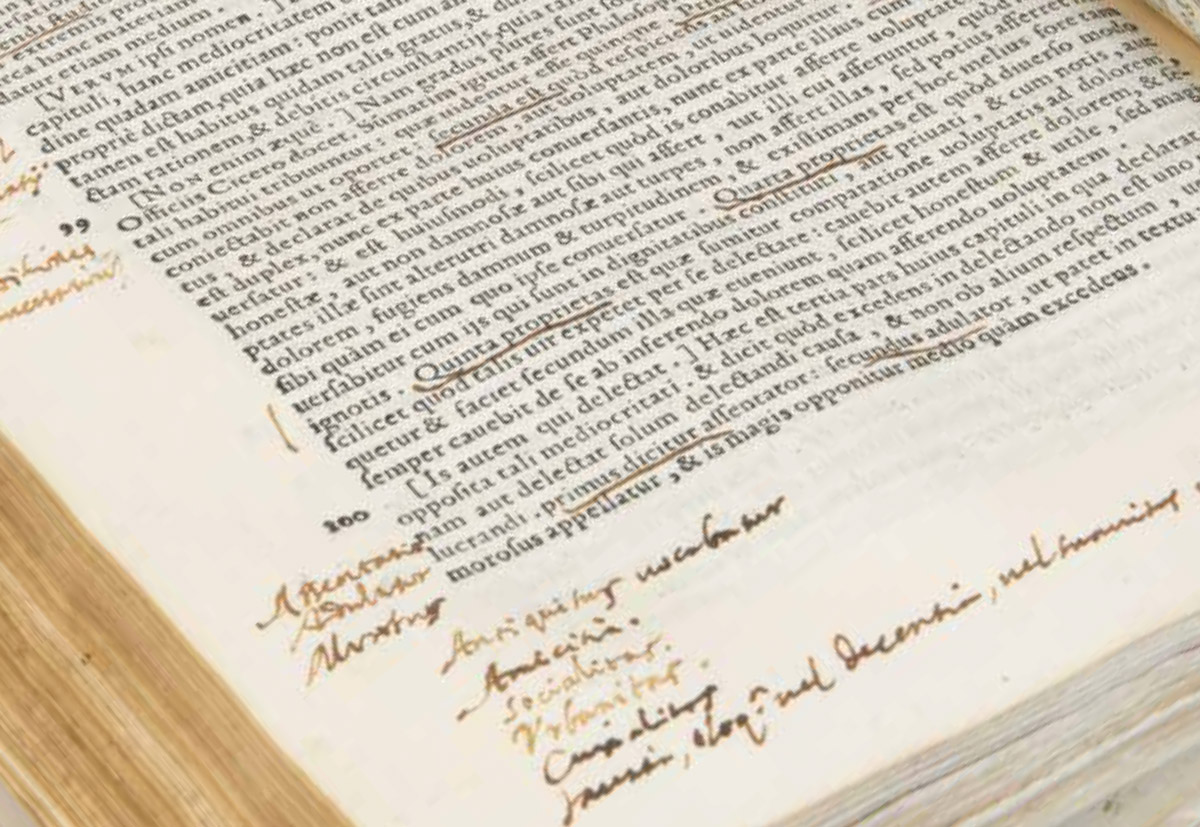

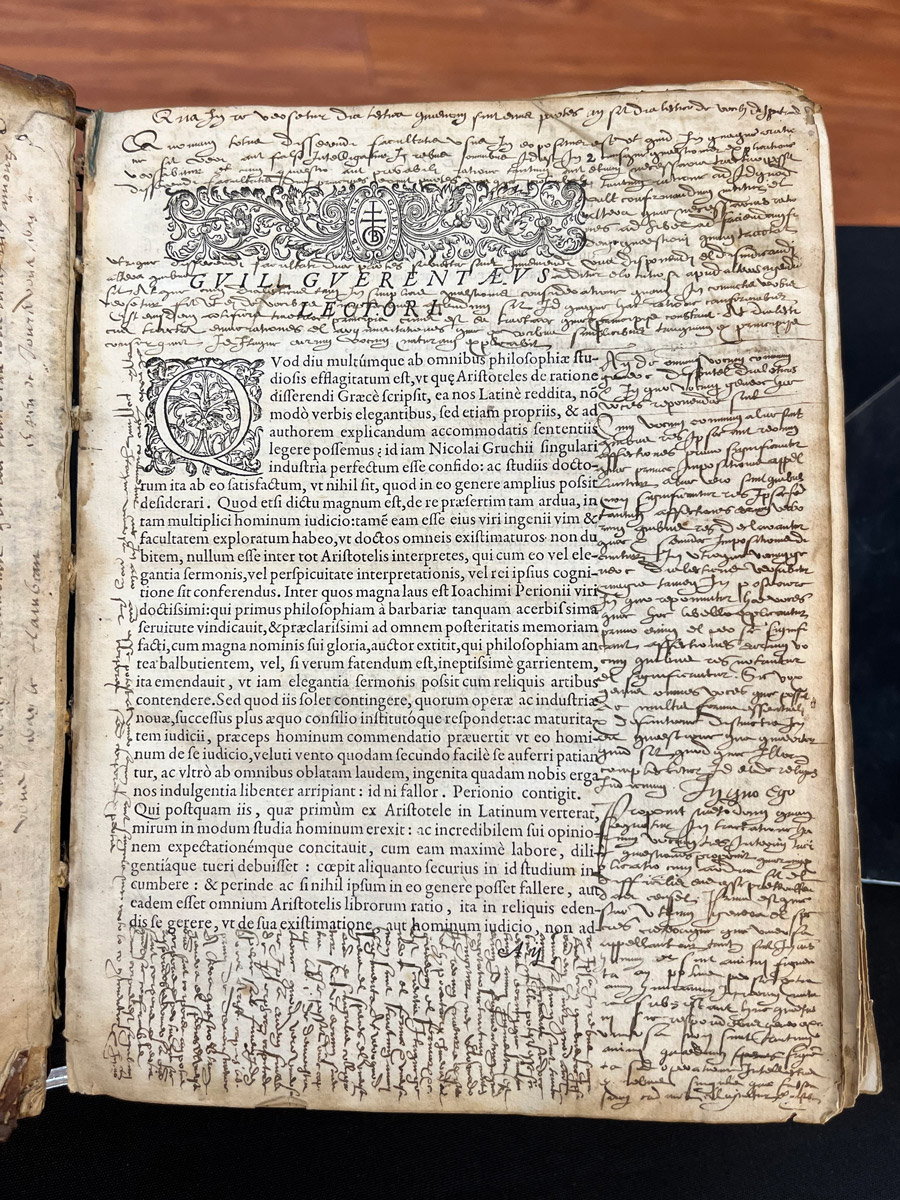

- Aristoteles, Ethica Nicomachea, 1565; marginalia

Image 2 Aristoteles, Ethica Nicomachea, 1565, p.184

Image 3 Aristoteles, 1565

With this example, we were able to show students non-destructive additions to the text, called marginalia, and show notes coming from different individuals, commenting and interacting with one another about the arguments present in Aristotle’s work. The purpose was to highlight how marginalia can be considered secondary source material and how it creates additional value to the primary source.

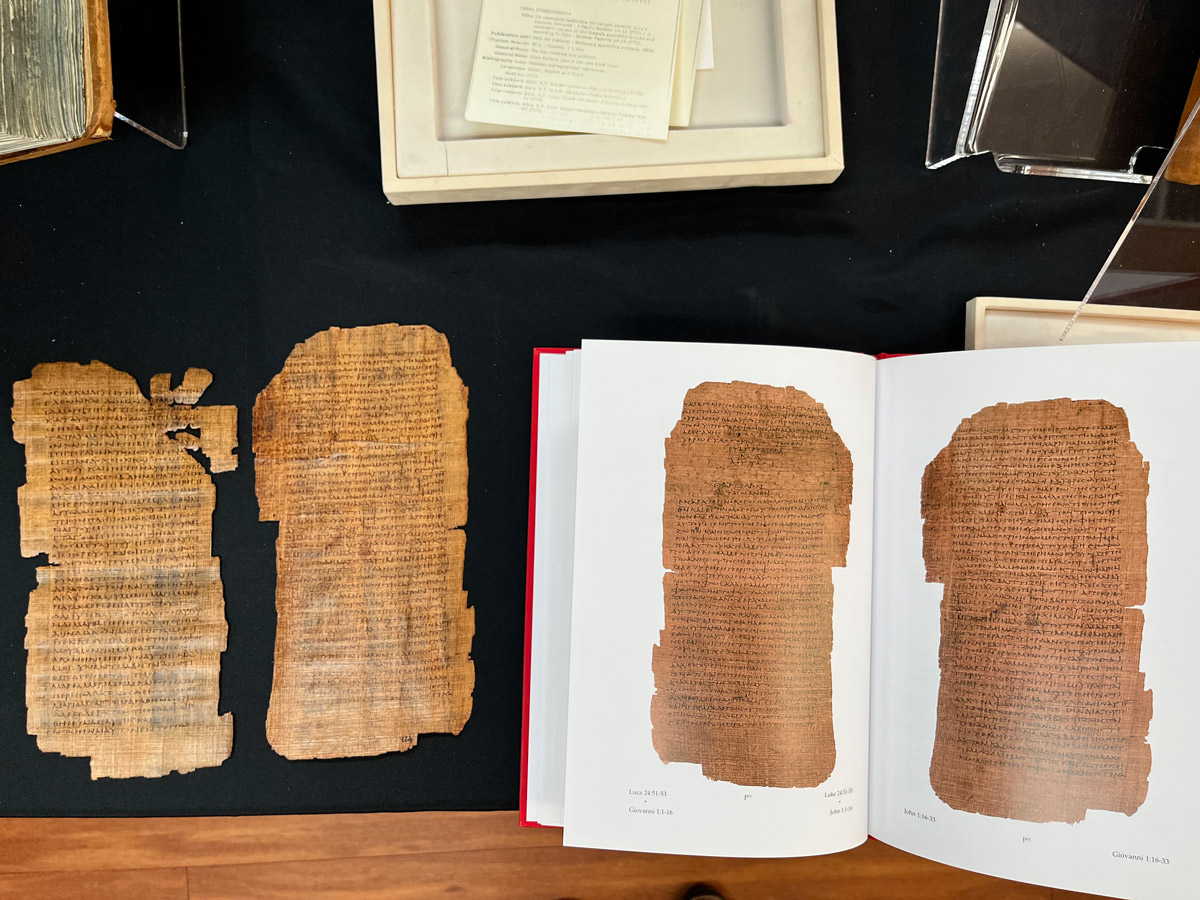

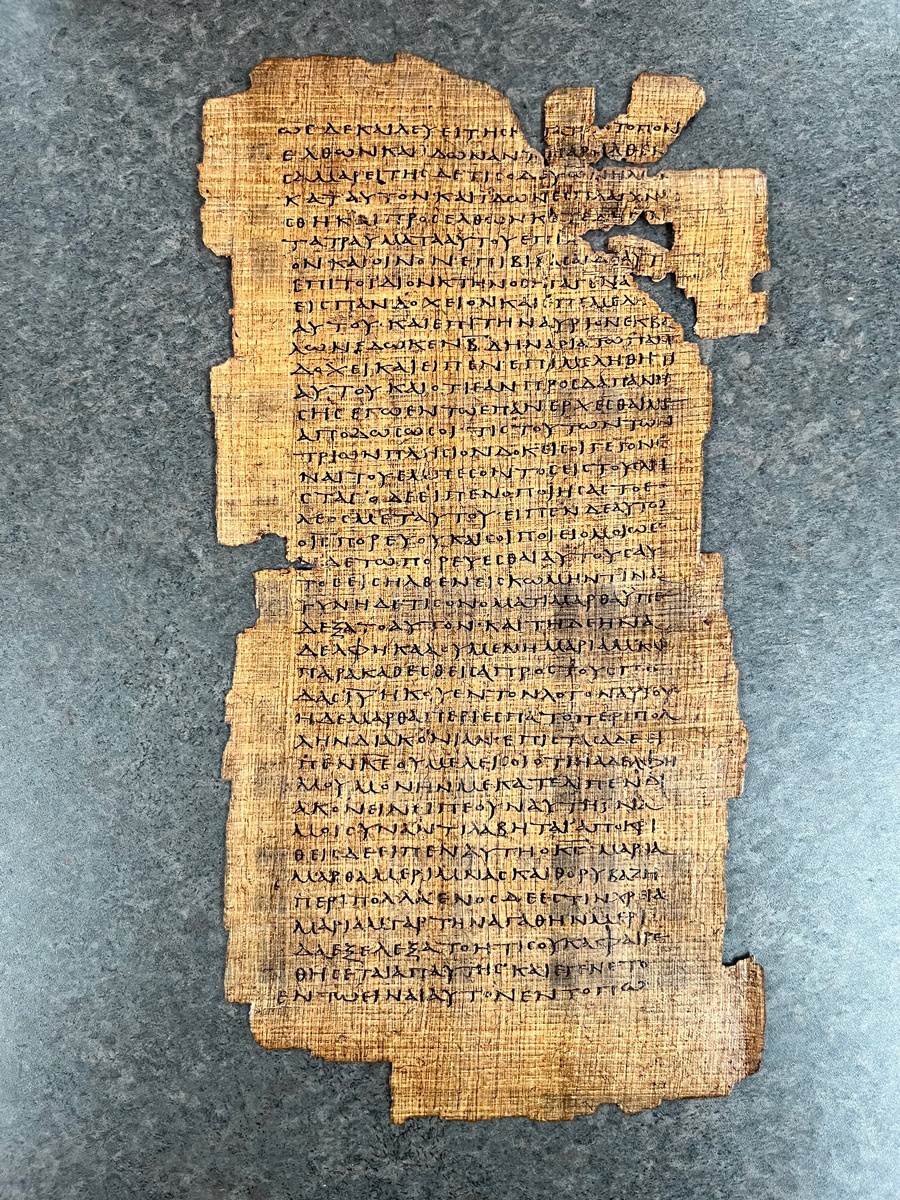

- Bodmer papyrus, p. 75; Gospel of John & Luke

Image 4 Bodmer papyrus, p. 75, Gospel of John & Luke

Image 5 Caption: Bodmer papyrus, p. 75, Gospel of John & Luke

This work is a facsimile; however, it is a very important piece of written word for Christians worldwide. The papyrus facsimile, produced by the Vatican, includes parts of the Gospel of Luke and John. This piece is the oldest surviving text of Luke known and includes the Lord’s Prayer. In addition, this facsimile served a pedagogical function to invite the students to notice that there are no separations between the letters in ancient Greek. This can make it more difficult for the modern undergraduate to decipher the text.

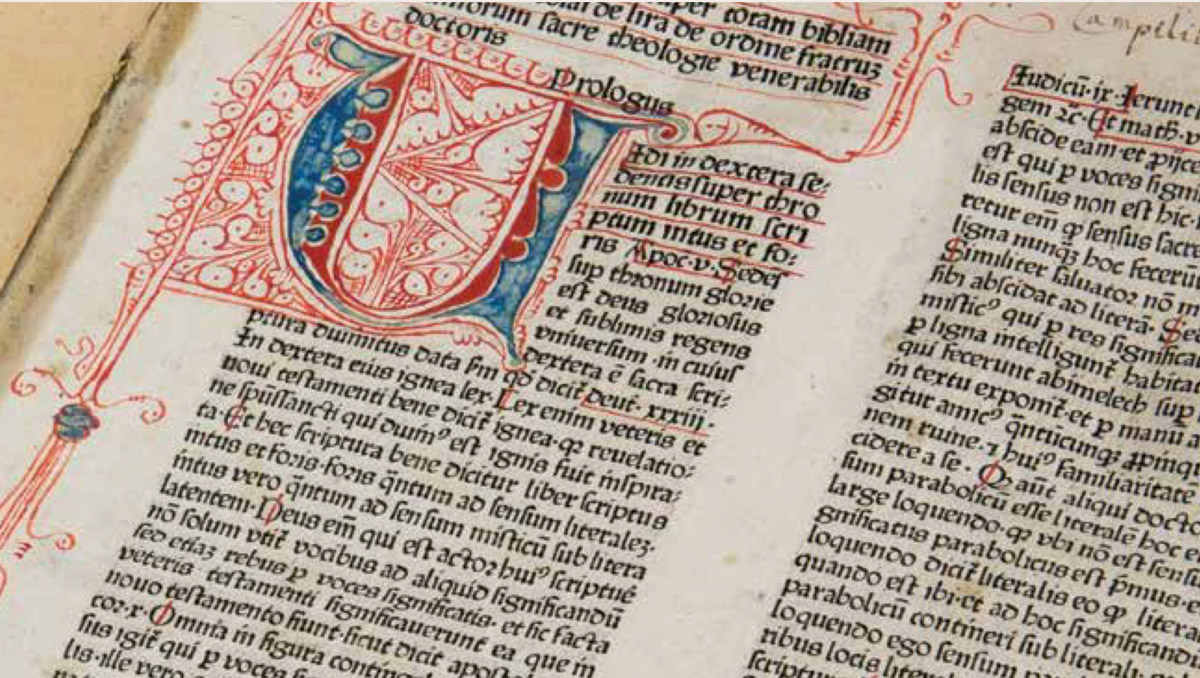

- Nicolaus de Lyra, Moralla super totam Bibliam, 1481; illuminations

Image 6 Caption: Nicolaus de Lyra, Moralla super totam Bibliam, 1481

This work was produced in the early printing period, incunabula; the coloring was the focus of the instruction, looking at the stylization of capital letters and coloring done in the book.

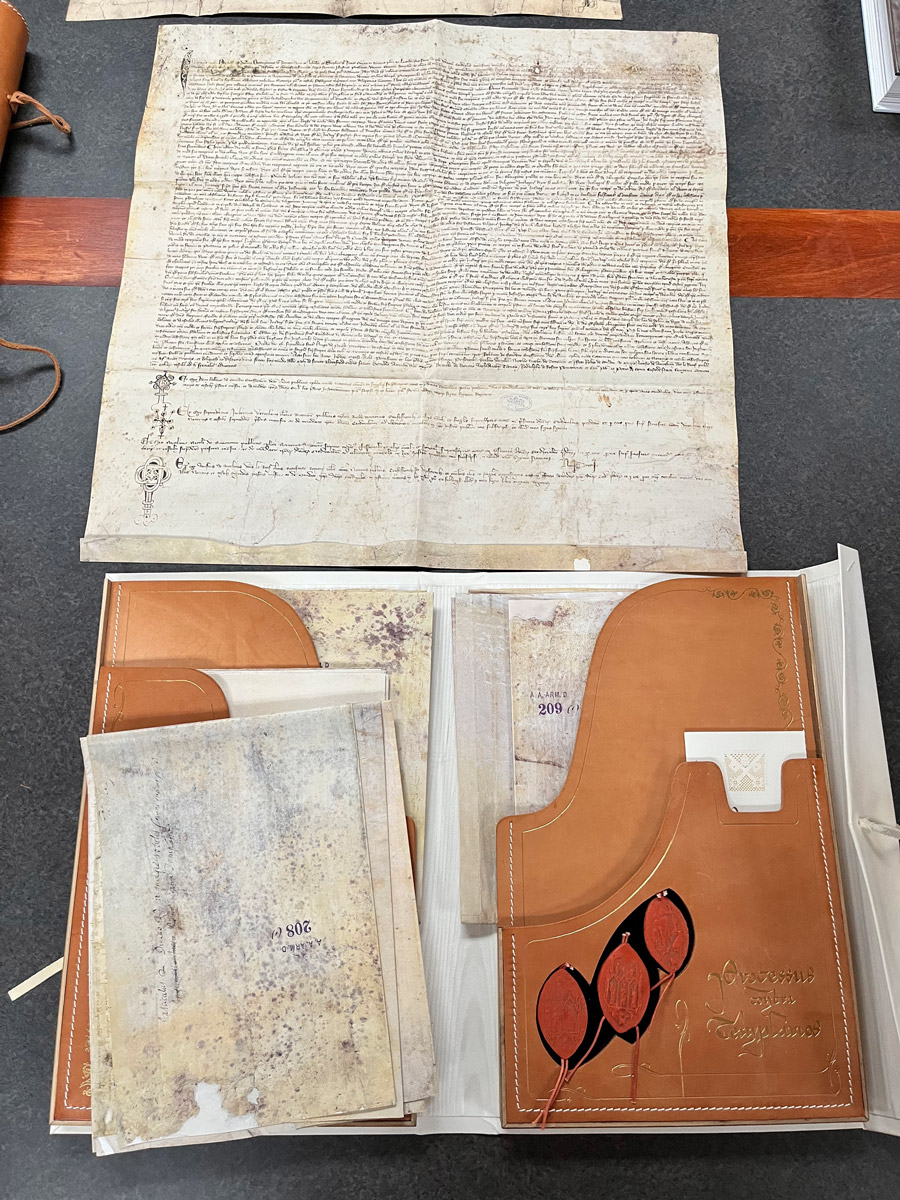

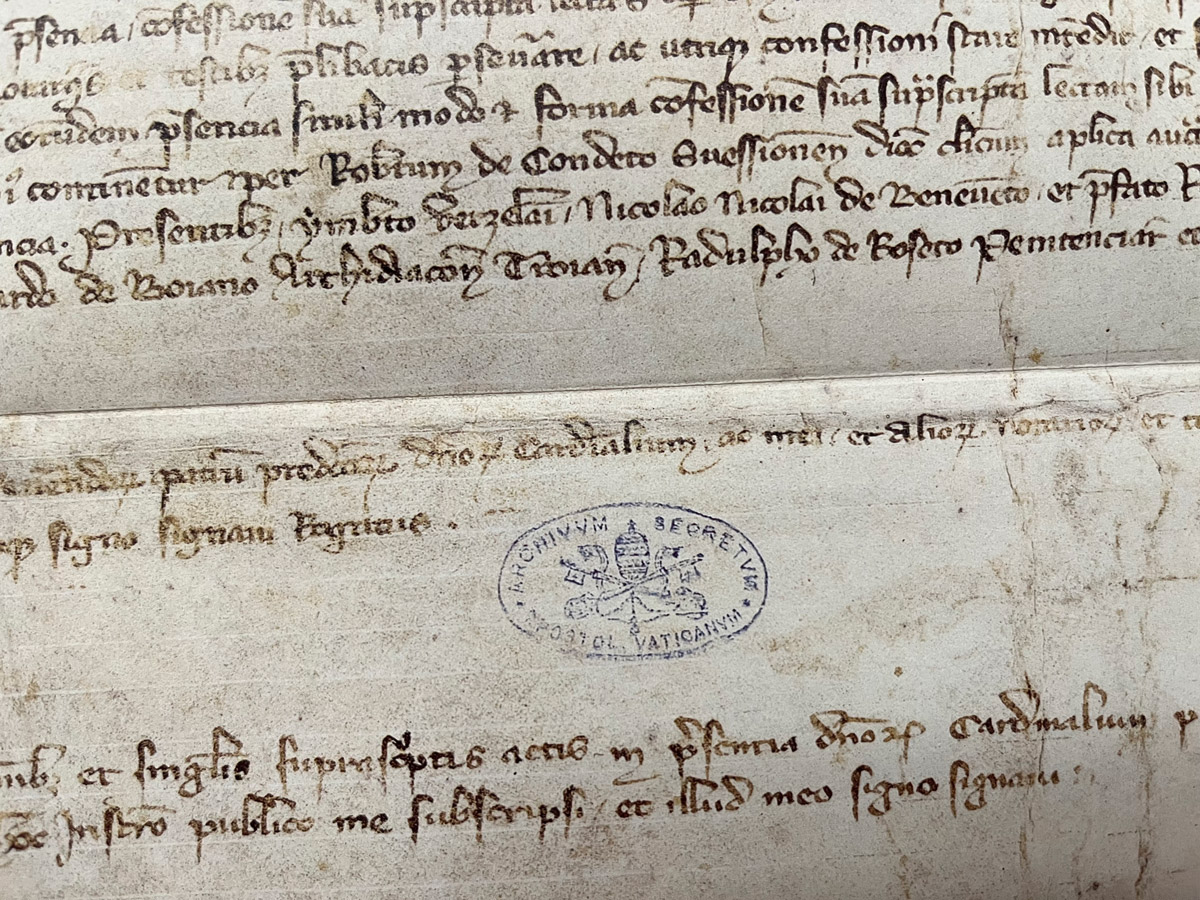

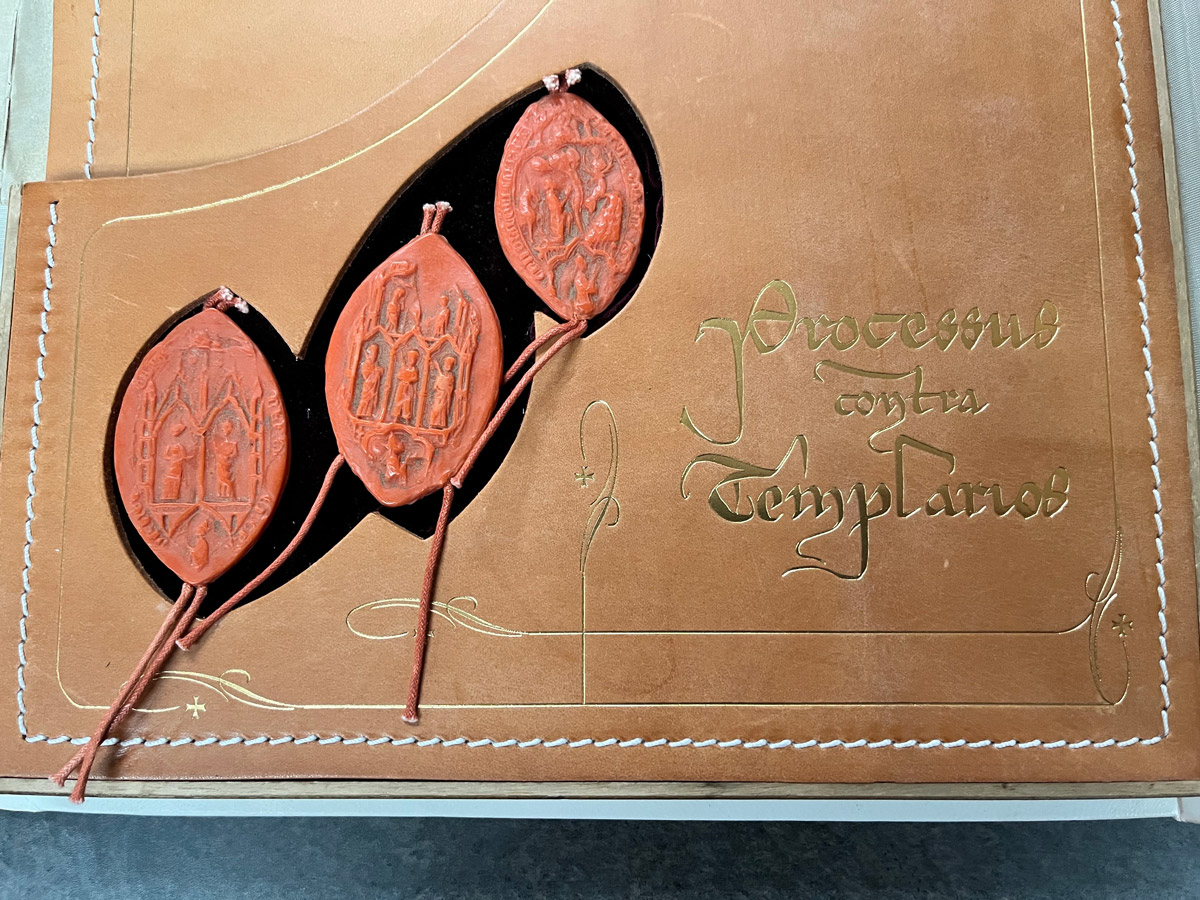

- Parchments of the hearings of the Trial against the Knights Templar (1308), Vatican Apostolic Archives, Archivum Arcis Arm. D208, 209, 210, 217

Image 7 Trial against the Knights Templar (1308/2007)

Image 8 Facsimile of the Trial against the Knights Templar (1308/2007)

Image 9 Facsimile of the Trial against the Knights Templar (1308/2007)

This multi-volume piece is a facsimile of the original (partly produced on vellum) produced from the Vatican Apostolic Archives, formerly called the Vatican Secret Archives. It shows the court processes and documentation against the Knights Templar in the early fourteenth century, and contains additional resources added to the works. It was a good demonstration of an important historical work that carries a lot of historical and fictional references.

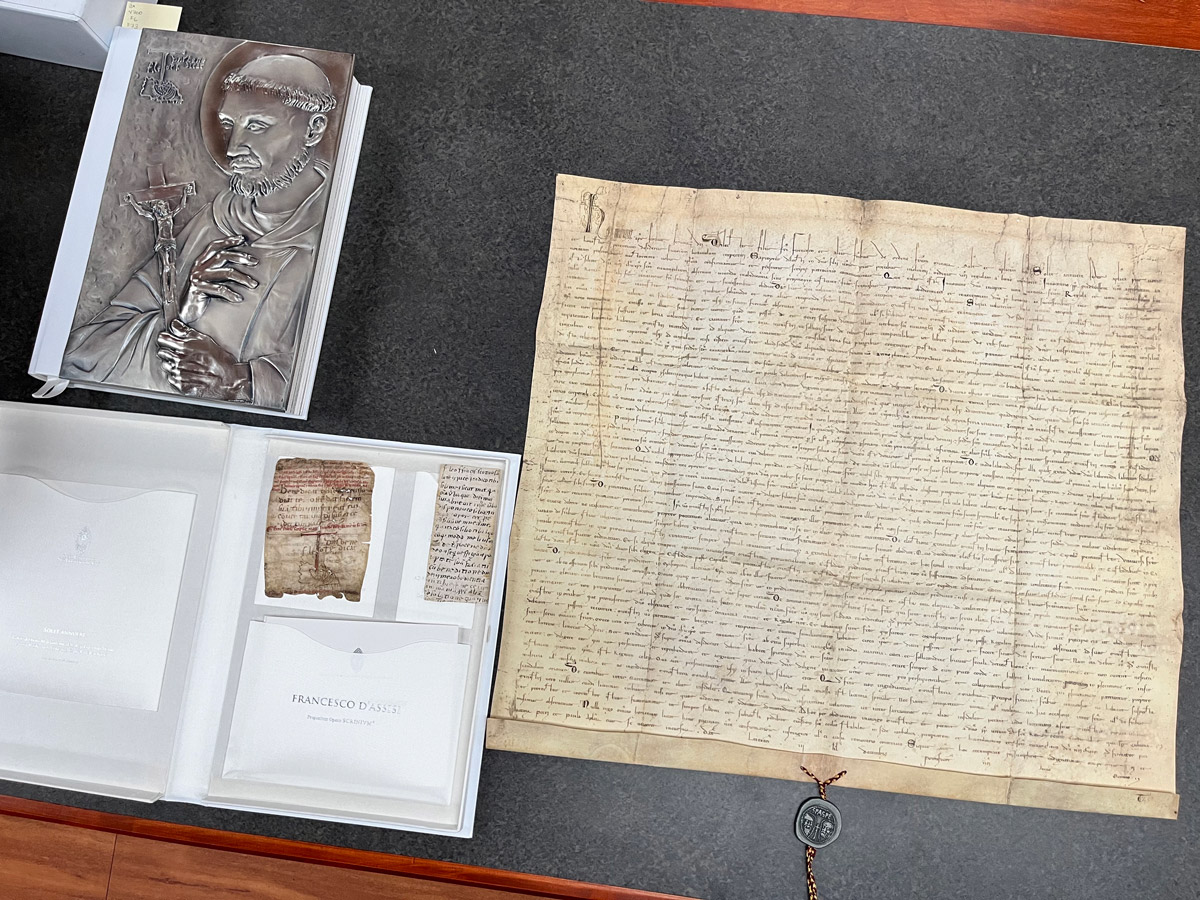

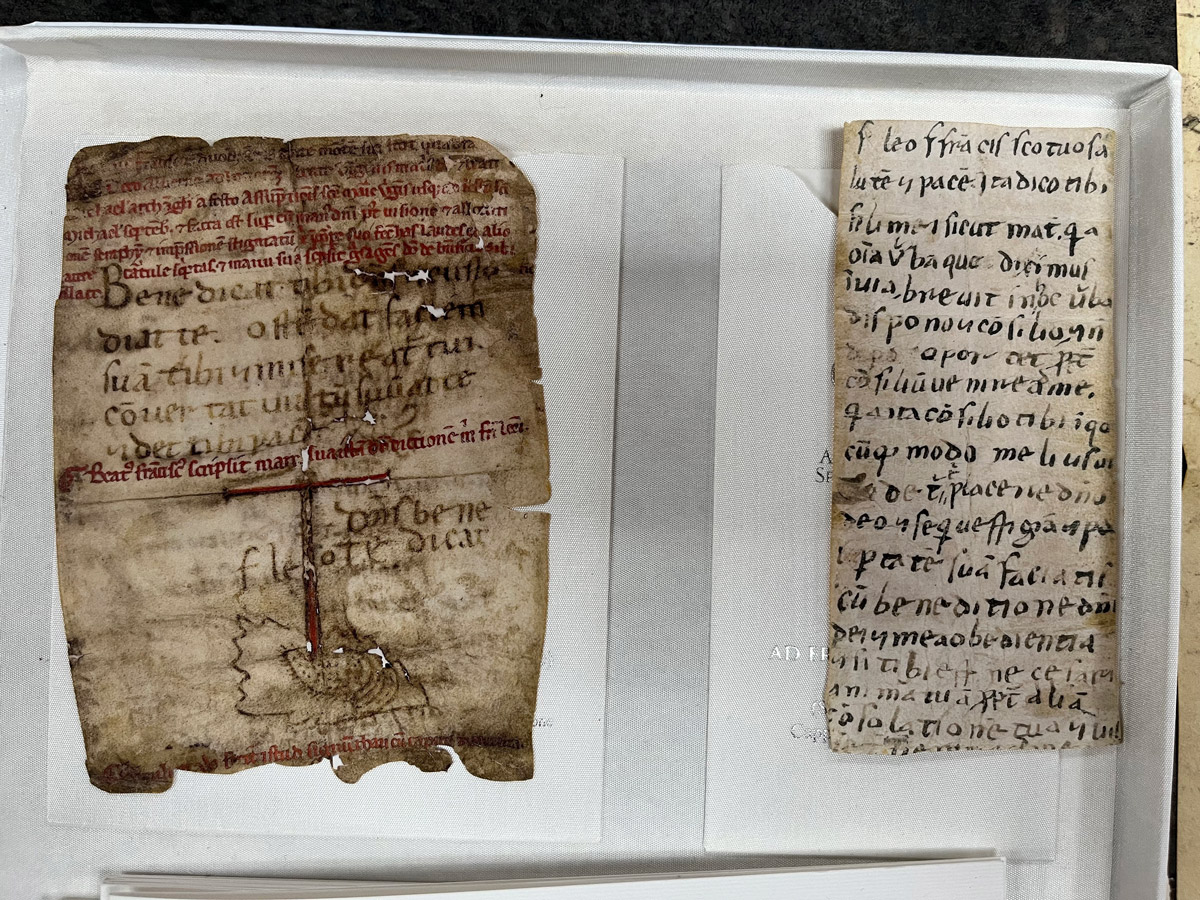

- Solet annuere and texts written by St. Francis in his own hand, Lower Basilica in Assisi / Cathedral of Spoleto

Image 10 Facsimile of the Pope Honorius III, Regula Bullata, 1223

These documents are facsimiles that come from the Vatican Archives and were produced by Scrinium. The large document is entitled the Regula Bullata, produced in 1223, and contains the letter of Pope Honorius III, who has officially confirmed the Rule (the Later Rule) of the Franciscan order, written by St. Francis of Assisi for his community.

Image 11 Facsimile of the St. Francis of Asissi, Assisi chartula

The two small documents have a very unique value. They are believed to be the only surviving texts with the handwriting of St. Francis of Assisi. The parchment document on the left is known as the Assisi chartula, St. Francis’s writing of Laudes Dei Altissimi. The document on the right contains the Blessing for brother Leo.

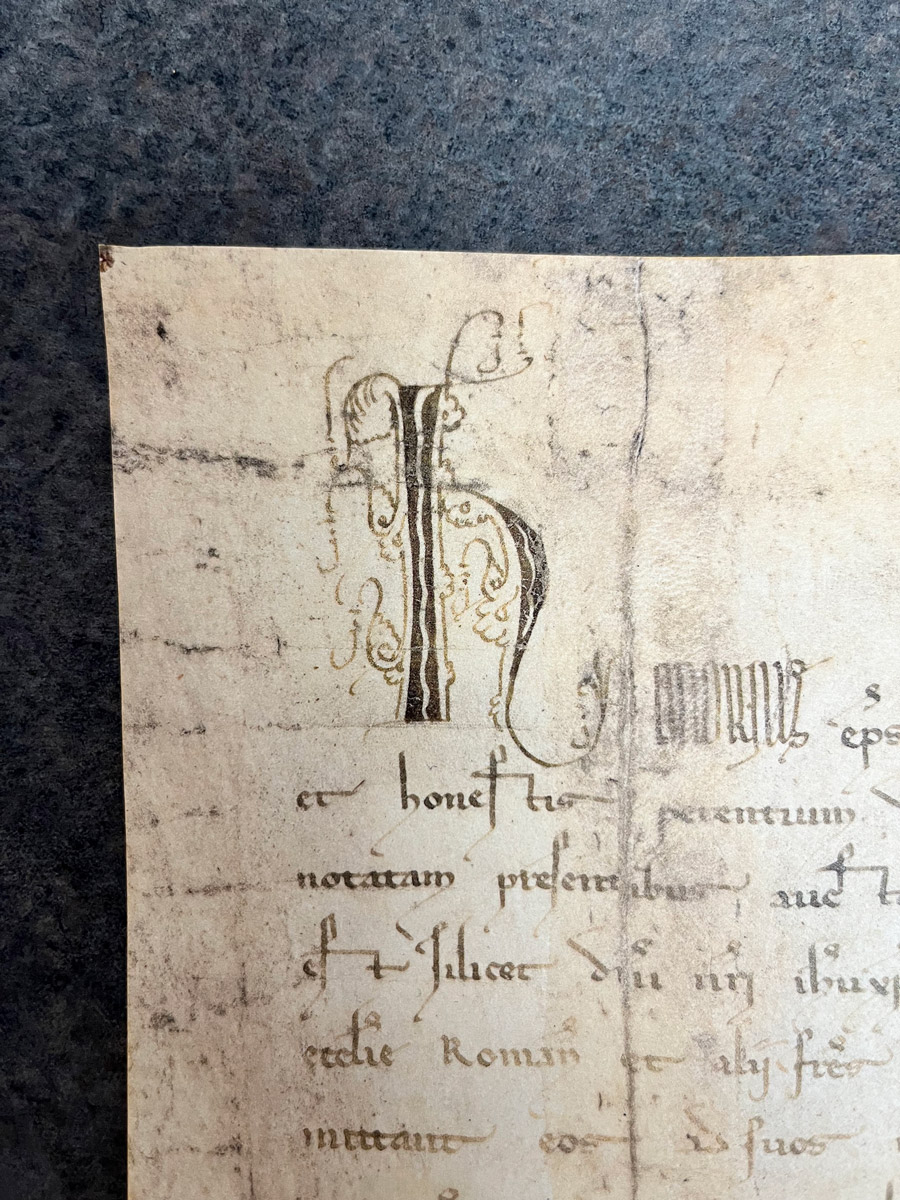

Image 12 Facsimile of the Pope Honorius III, Regula Bullata, 1223, signature of the Pope

In this collection of documents, specifically on Regula Bullata, we can see the papal signature hidden in the first initial letter: if we look closely at the delta around the H, we will find the text Bene Valete, which was the papal signature.

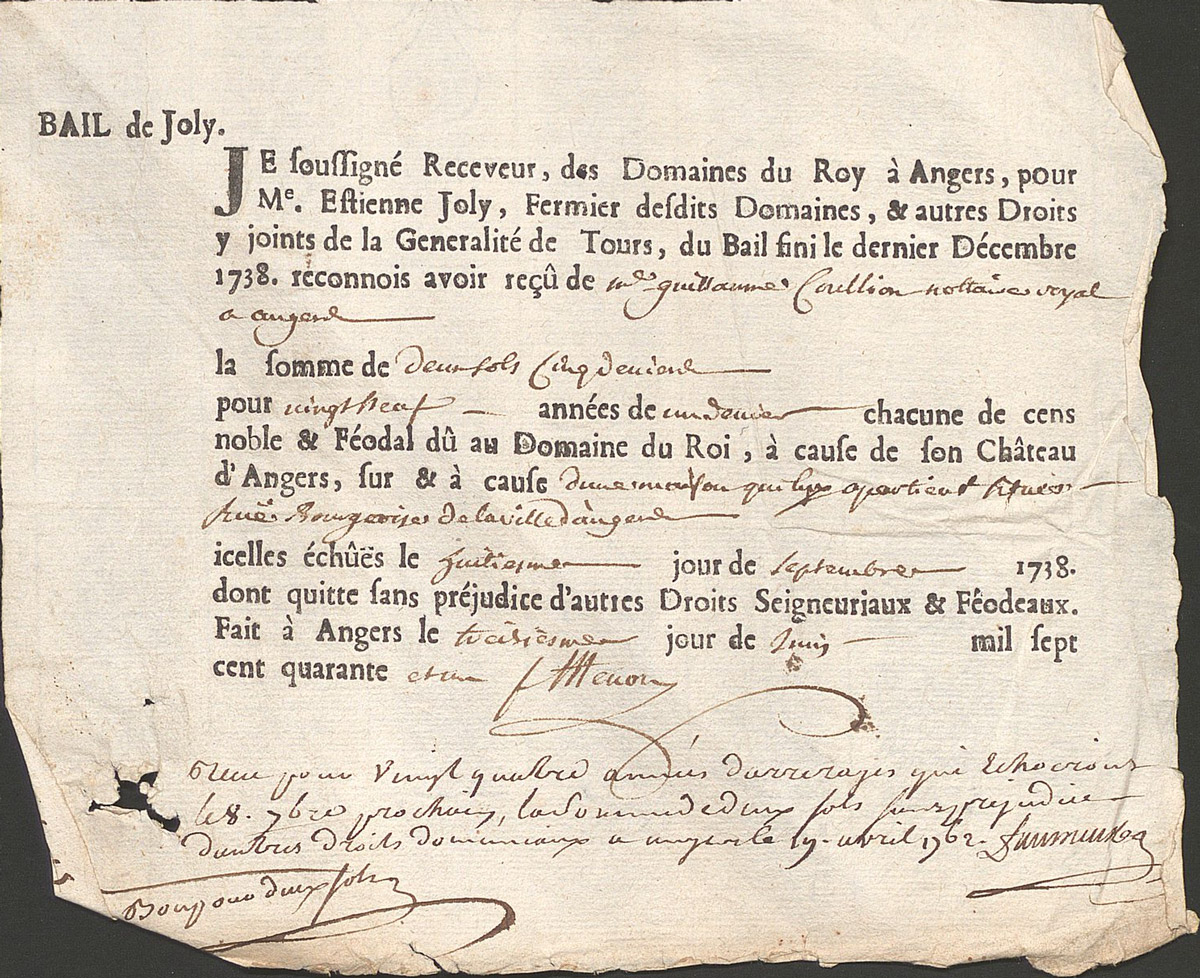

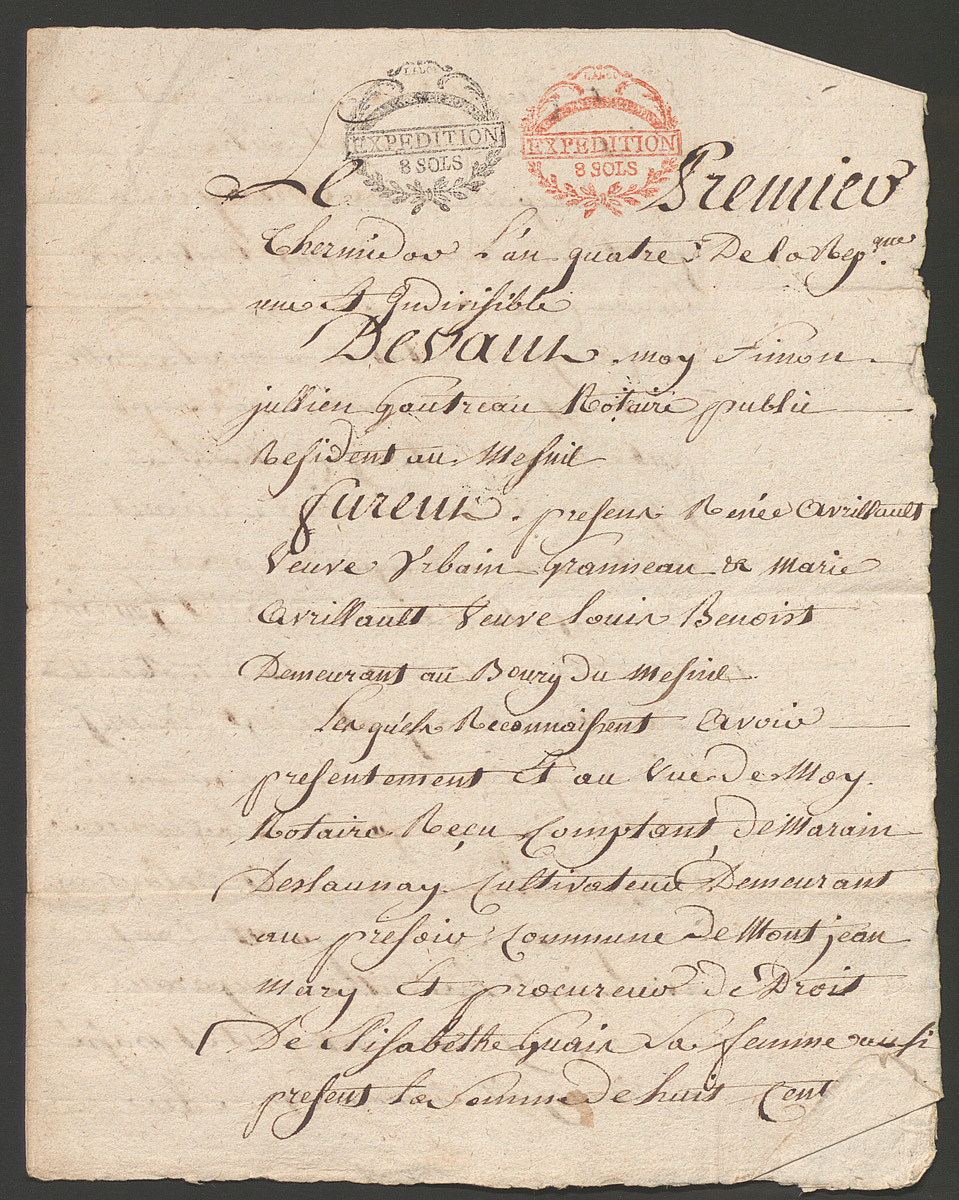

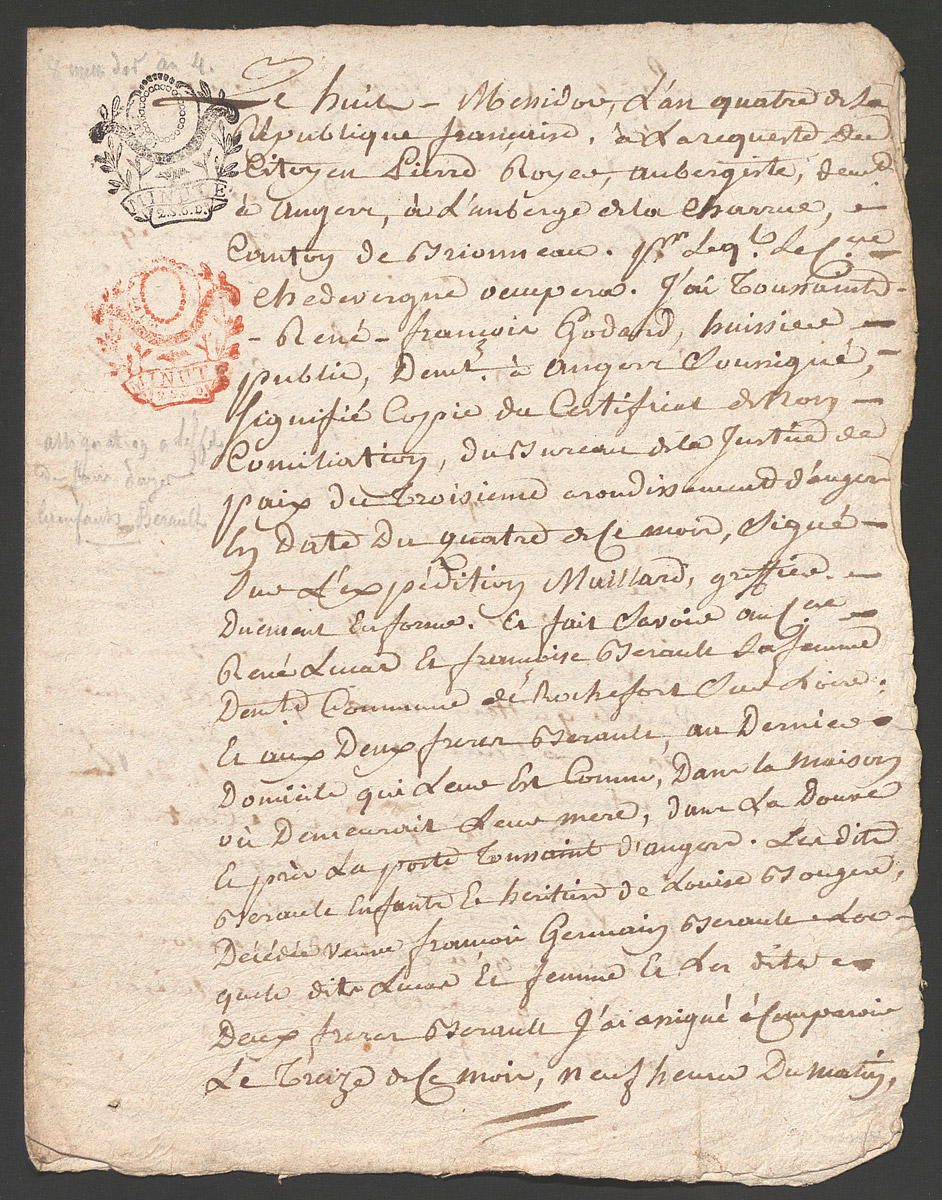

- Contractual agreements & letters

Image 13 Lease agreement from Angers, France dated 1738

Image 14 Letters, 17th century

Image 15 Letters, 17th century

Various handwritten legal and contractual documents were shown to students, focusing on the content of the documents. Direct questions were asked: what can you learn and discover when you look at these documents? Students were also tasked with identifying other important pieces in the documents, such as seals, stamps, signatures, and marginalia comments. They were invited to think about how they contribute to the significance/meaning/comprehensive weight of the document.

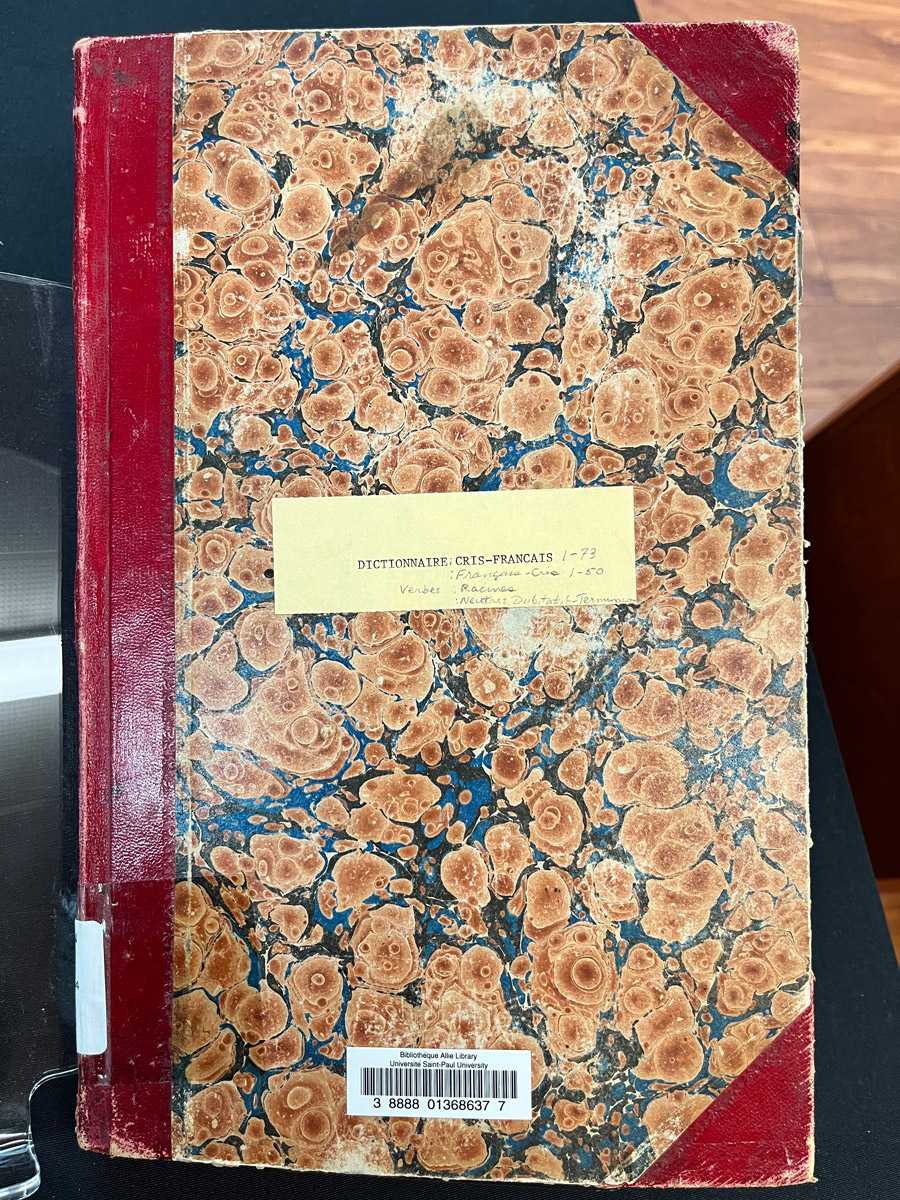

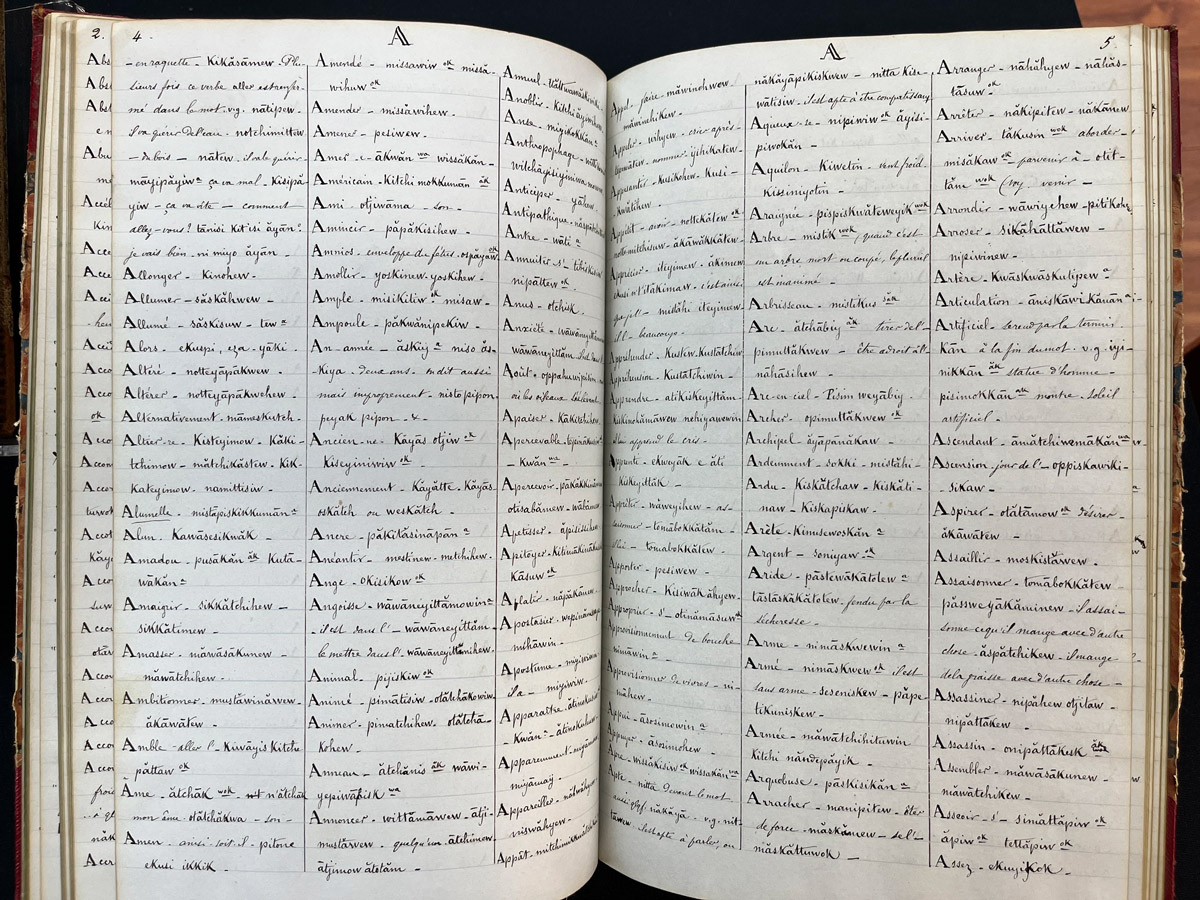

- Indigenous languages dictionaries

Image 16 Late 19th-century manuscript dictionary in Cree-French

Image 17 Late 19th-century manuscript dictionary in Cree-French

The library also has a variety of manuscripts, and a few Indigenous dictionaries were shown to students. Here we focused on the languages, historical meanings, and discovery.

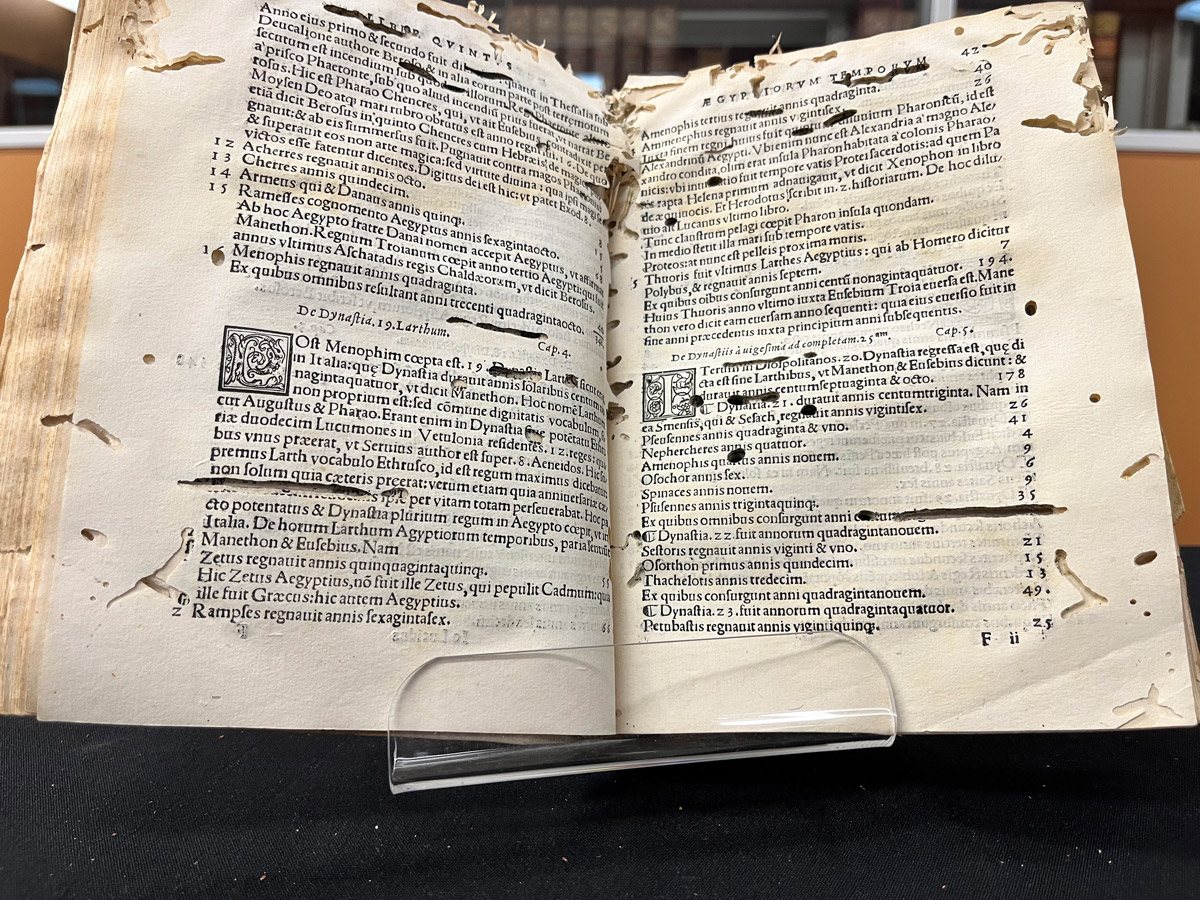

- Joannes Lucidus, Samothei viri Clarissimi, 1546

Image 18 Joannes Lucidus, Samothei viri Clarissimi, 1546 (bookworm damage sample)

Image 19 Joannes Lucidus, Samothei viri Clarissimi, 1546 (bookworm damage sample)

This last piece was very much for the show. Since most undergraduates do not realize that “bookworm” is not just a phrase but an actual pest, we took this opportunity to tell them about book worms, their quest for glue and eating paper, and how printers over the years have looked at addressing the issue. We discussed how, today, our rare book room is free of any literal bookworms that eat books, but we have several people on campus who are passionate about books!

Findings of this Study

Reflection Assignment

After a visit to the Rare Book Room at the Jean-Léon Allie Library, students were asked to write a short personal reflection about their visit to Rare Book Room. This assignment was optional, and students who submitted it would automatically receive five bonus points in the labs. It was highlighted that students did not need to do any additional research. The length of the assignment was one to two pages maximum, double-spaced.

If students were not able to be present at the presentation, they still had an opportunity to submit this bonus assignment. They were presented with an alternative resource; see the tutorial from USC libraries (https://scalar.usc.edu/works/primary-source-literacy---an-introduction/index and the video “From the Archives” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSUM1MYfMOc).

The guiding questions for students’ reflections included the following prompts:

- What are some takeaways from your visit to the Rare Book Room?

- Did the visit to the Rare Book Room change your perspective on research? How?

- Why is it important to use primary sources in research? How did the visit to the Rare Book Room inform your opinion on this issue?

- How will this visit affect your research in the future?

The goal of this assignment was to help students reflect on the importance of primary sources in research and help them to more deeply understand the concepts related to primary source literacy that will inform their studies at the university.

Student demographics

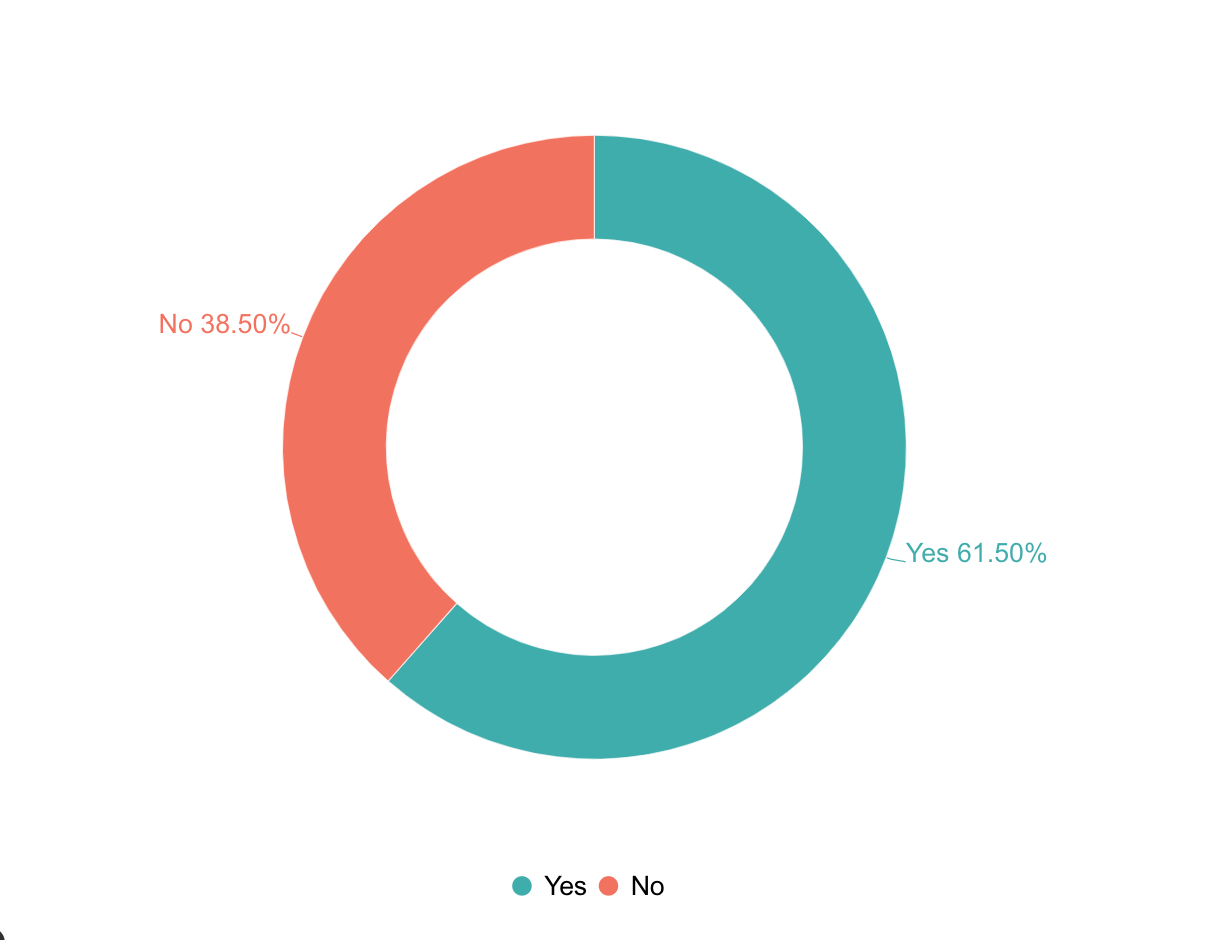

Out of 13 students who were registered in the course, 61.5% (eight students) submitted the reflections (see figure 2). All eight students attended the presentation in-person at the Rare Book Room.

Figure 2 The number of students who submitted reflections

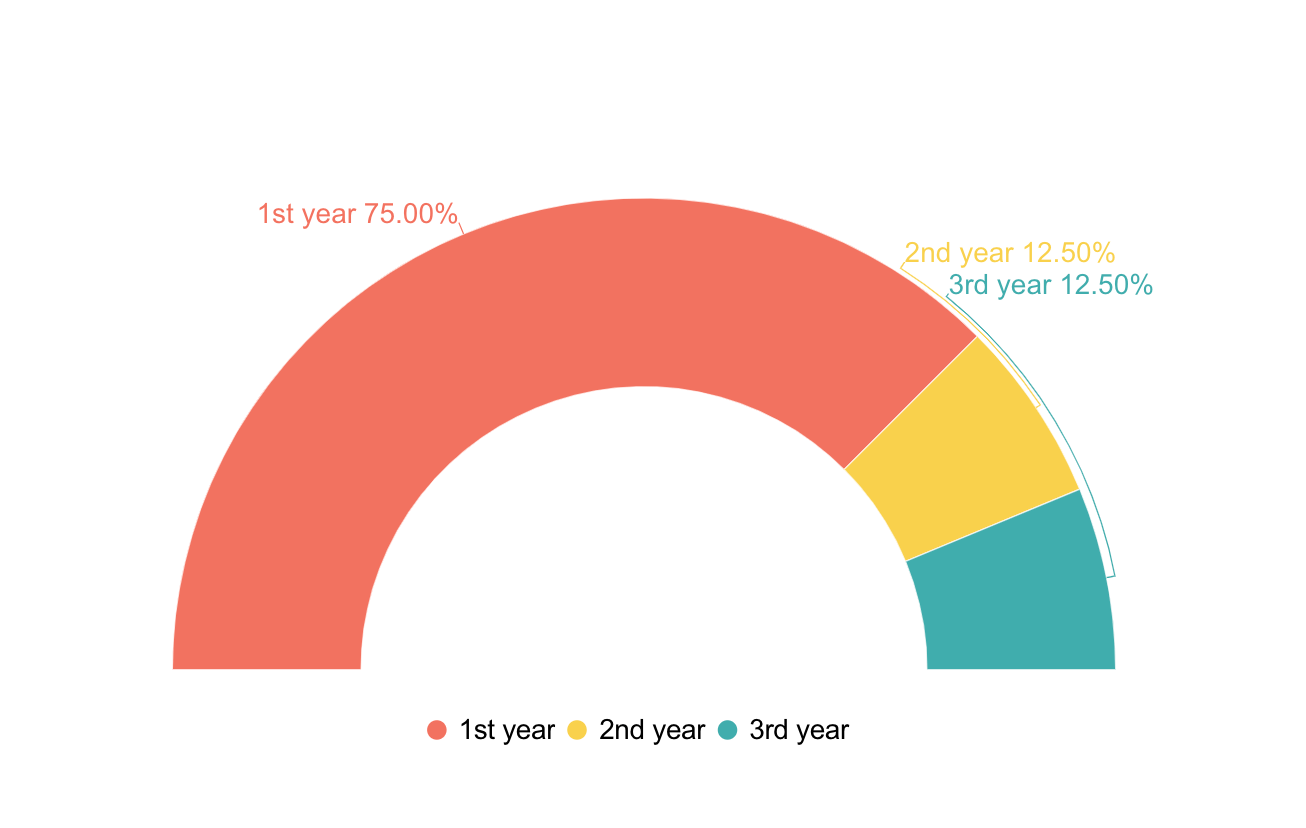

It is important to note that both high and low-achieving students completed the reflections. There is no correlation between their program of study, age, or any other characteristics and competing their reflection assignment. A majority of students (75%), who completed the assignment were in their first year of studies, and a few students were in their second and third years of study (See figure 3).

Figure 3 Year in the undergraduate program of those students who completed the assignment

Analysis of students’ reflections

Students’ reflections were analyzed using thematic analysis. The themes that emerged included: appreciation of the rare books, the importance of primary sources, the impact of the visit on their view of research, future use, and critical thinking skills. We will discuss these themes in detail below.

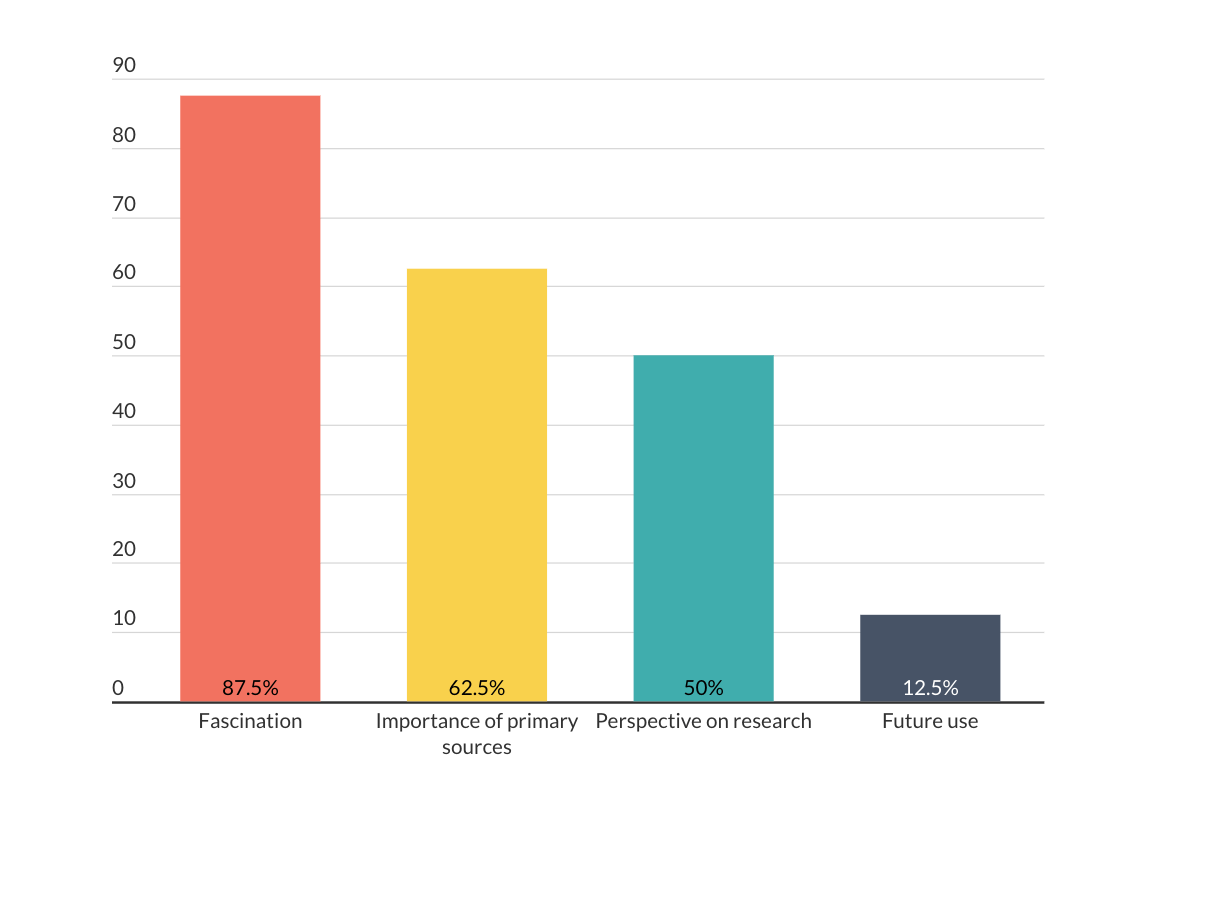

Appreciation of the rare books. Students have expressed a strong fascination with the rare books, as well as with the spaces that they visited. These “affective responses that come from engaging with physical materials” play an important role in the development of primary source literacy, as the students associate positive feelings with this experience (Kiser et al. 2023, 498). In total, 87.5% of students expressed strong feelings of fascination and awe about their experience (see figure 4). They have stated that this experience was “fascinating,” “eye-opening,” “cool,” and “interesting.” They felt awe and gratitude for this visit. Students wrote:

“Being visually able to see books that have such history to them (whether it be the content, the materials, or art work) was something that left me in awe.”

“Before the visit, I was worried I would be terribly bored [...]However, when we got there, I felt the room was almost like a treasure chest with all the old books.

Figure 4 Analysis of students’ reflections

Importance of primary sources for research. Students highlighted that the visit helped them understand why it is important to go to a direct source and to properly identify the difference between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, and 62.5% of students expressed that this visit helped them understand the importance of using primary sources in research (see figure 4). They stated that it was “invaluable for research” due to containing “first-hand information,” it helped them develop critical thinking, and better understand authority. Students wrote:

“Primary sources bring authenticity and authority to research, and are the best way to have a complete and accurate research paper.”

“We must understand the past to understand the present. These books allow students to develop critical thinking skills when considering their research.”

“The visit to the Rare Book Room reminded me how important it is to get information from primary sources; these are stories and documents told from the perspectives of writers and authors who were experiencing these historical moments and cultural touchpoints and making observations that modern writers could not.”

This indicates that students see value in becoming familiar with these materials and can transfer this understanding to their course assignments.

Impact of the visit on students’ view of research. Many students identified that this visit will change how they do research in the future, and 50% of students highlighted the importance of using primary sources in their research (see figure 4). They mentioned that the visit broadened their knowledge, helped them understand the importance of using primary sources in future research, and helped them appreciate the research that has been done so far. They wrote:

“My visit to the rare book room changed my perspective on research by better defining what a primary resource is.”

“In the future, I will be considerate of using the past to discover knowledge. It reminds me that there is a past in we must understand where some research starts and witness the progression of research first hand to get a broader lens to peer through when doing any type of research.”

Future use of the Rare Book Room. The use of rare books is very discipline-specific with 12.5% of students saying they will use the Rare Book Room resources in the future (see figure 4). This, however, does not indicate that the visit was unsuccessful. While many students did not see how they could use these books for their research in the future, they noted this visit was still very eye-opening and left a significant impact on their learning. Here is what the students had to say:

“I am now thriving to tie-in the research involved in my life’s work to a question answerable only by a rare-book, an option I had not considered until being in that environment.”

“While I personally don’t see myself ever heading down to the basement for research purposes, it has left a lasting impact on me, in terms of my research methods.”

“In the future, I don’t think I’ll be visiting the room again to use the sources necessarily, [...] however, I would visit again just to be marveled at its contents.”

Critical Thinking and Evaluation. Students have also demonstrated strong critical thinking about the source of information and authority. Students stated:

“My main takeaways from my visit to the rare book room was how much social media and “fake news” has truly transformed our society. I had always thought “info is info” as long as it sounds good. But, I learned that is definitely not the case”.

“The data and studies for any research starts with finding the correct sources, and primary sources are by far the most valuable in terms of getting the thoughts and reflections of those who experienced or studied moments, people and events throughout history.”

This indicates that students learn to apply their understanding of primary sources to their current context by critically evaluating the source and understanding it before they read or work with it.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned

This study allowed us to explore the impact of the Rare Book visit on the development of primary source literacy among undergraduate students. Through this visit, students learned to appreciate the historical significance of these books, as well as understand the importance of these primary documents for academic research. Despite some students indicating that they do not see themselves using these books in the future, the evidence strongly suggests that students started to appreciate the importance of primary sources when it comes to their research. In addition, students improved their critical thinking skills and understanding of authority, an essential part of the IL curriculum. Primary source education can help in developing these core skills and help students appreciate the importance of looking at the original source of information.

Library spaces and collections are essential for cultivating primary source literacy in undergraduates. The physicality of the rare book material is essential for the experience of students (rather than just accessing information online via library catalog or internet archives). The students identified the aesthetics of a rare book and hands-on experience as important in this process. It is also beneficial for students to have a little “field trip” to the library (Hubbard and Lotts, 2013).

One student stated: “The rare book room at Saint Paul is a unique and special treasure cared for by intensely passionate people.” This was an acknowledgment of the importance of not only our well-curated collection and spaces but also the personnel who invest time and energy into educating students about these resources. This also opens the door for students to use library spaces and consult librarians in the future.

We have seen many benefits from introducing students to rare book materials, and we know that in-depth exploration and work with rare book materials could benefit certain students even more. While this visit provided only a brief introduction to the rare books, it is important to continue this work with rare books relevant to students’ various disciplines. One example of such work is Guided Resource Inquiry, offered by Jarosz and Kutay (2017). Additionally, Davis (2021) demonstrates how to do it with historical photographs, while Duncan and colleagues (2023) utilize text messages to teach students about primary source literacy.

Overall, this study has demonstrated the immense benefits of primary source education through the collaboration between professor and librarian in the credit-bearing IL course. This collaboration has provided countless benefits to current students, who have developed primary source literacy and hopefully become better equipped to continue their undergraduate studies.

If you would like to get familiarized with some of the rare book materials at Jean-Léon Allie Library, Saint Paul University, please consult the links below:

- Rare Books and Special Collections (SPU): https://ustpaul.libguides.com/rare

- Presentation-related files: https://tinyurl.com/primarysourcesATLA2023

References

ACRL. 2018. “Guidelines for primary source literacy.” February 12, 2018. https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/Primary%20Source%20Literacy2018.pdf

Archer, Joanne, Ann M. Hanlon, and Jennie A. Levine. 2009. “Investigating Primary Source Literacy.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 35 (5): 410–20.

Craig, Heidi, and Kevin M. O’Sullivan. 2022. “Primary Source Literacy in the Era of COVID-19 and Beyond.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 22 (1): 93–109.

Crisp, Samantha. 2017. “Collaborating for Impact in Teaching Primary Source Literacy.” SAA Case Studies on Teaching with Primary Sources 1: 1–11.

Daines, J. Gordon, and Cory L. Nimer. 2015. “In Search of Primary Source Literacy: Opportunities and Challenges.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 16 (1): 19–34. .

Davis, Daniel. 2021. “Using Visual Resources to Teach Primary Source Literacy.” Journal of Western Archives 12 (1): 1–17.

Duncan, Lisa, Feeney, Mary, Mery Yvonne, and Niamh Wallace. 2023. “TTYL: Designing Text-Message Based Instruction for Primary Source Literacy.” In Forging the Futures, edited by D. Mueller, 502–510. ACRL 2023 Proceedings. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/conferences/acrl2023/papers

Hubbard, Melissa, and Megan Lotts. 2013. “Special Collections, Primary Resources, and Information Literacy Pedagogy.” Communications in Information Literacy 7 (1): 24–38. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2013.7.1.132.

Jarosz, Ellen, and Stephen Kutay. 2017. “Guided Resource Inquiries: Integrating Archives into Course Learning and Information Literacy Objectives.” Communications in Information Literacy 11 (1): 204–20. .

Kiser, Paula, Larson, Christina, O’Sullivan, Kevin, and Anne Peale. 2023. “Primary Source Pivoting: How Faculty Adapted Primary Source Instruction During the Pandemic and What is Here to Stay.” In Forging the Futures, edited by D. Mueller, 495–501. ACRL 2023 Proceedings. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/conferences/acrl2023/papers

Malkmus, Doris J. 2007. “Teaching History to Undergraduates with Primary Sources: Survey of Current Practices.” Archival Issues 31 (1): 25–82.

Malkmus, Doris J. 2008. “Primary Source Research and the Undergraduate: A Transforming Landscape.” Journal of Archival Organization 6 (1–2): 47–70. .

Sutton, Shan, and Lorrie Knight. 2006. “Beyond the Reading Room: Integrating Primary and Secondary Sources in the Library Classroom.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 32 (3): 320–25.

Yakel, Elizabeth. 2004. “Information Literacy for Primary Sources: Creating a New Paradigm for Archival Researcher Education.” OCLC Systems & Services: International Digital Library Perspectives 20 (2): 61–64.