Why Print? Making the Case for Building Print Library Collections

Abstract: There are solid strategic reasons for libraries to continue collecting materials in print format, but these may not always be obvious to institutional administrators and others outside the library. Especially in the field of religious and theological information, print collections continue to be a significant resource for researchers. However, internal and external pressures at institutions with religion and theology programs have driven a desire to abandon print collections, often at odds with librarians. Librarians in the areas of religion and theology need to be able to make the case for widest possible access to important resources both in the present and in the future. I present a way to make this case on one sheet that is hopefully easy for non-librarians to understand. I also offer ideas of when and where to present this case.

Context and Introduction

Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS), which is based in Elkhart, Indiana (USA), on the traditional homeland of the Miami and Potawatomi, is a small freestanding seminary with numerous distance programs and a very small campus program. Fortunately, our seminary has invested in an excellent library over the years with both print and online resources and dedicated staff. Our library is housed in a beautiful LEED-certified green construction building that opened in 2007—the first theological library in North America to be LEED-certified (“Library | Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary” n.d.). I have been at AMBS in various library roles since 2008. During that time, I’ve seen a great deal of change from mostly campus-based programs and print-based library resources to where we are now, with mostly online programs and resources.

Atla is a significant professional community for me, and I know many of my colleagues are going through similar transitions. I will discuss how AMBS Library is handling some of these changes—hopefully in an adaptive way.

I don’t think I can dial back the clock to 2008. Many theological and religious studies librarians are likely in the same place. In this time of rapid change, though, I think it is unwise to abandon all tradition. We shouldn’t throw out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. I think that we need to make fresh cases for some more traditional aspects of librarianship as we attempt to serve our communities well.

Threats to Print Collecting

We’ve heard it all, haven’t we?

We as librarians periodically hear downright negative perspectives on print library collections. They get pejoratively called “dead tree books.” People assume that everything is online now (or at least everything that matters). I get questions from constituents about what we are doing in the library—from fellow administrators, from donors, from board members, and so forth. The implication of these questions is sometimes that we might be backwards or wasting time and money on something that doesn’t matter if we still care about print books. I’ve experienced this feeling like an assault on our profession, as if we are somehow now irrelevant in 2024

Many times, we know the reasons we still need to maintain print collections, but it can be hard to fend off all the questions and comments about it.

Reasons to Make the Case

I want to be proactive in my communication about our print collections for several reasons.

The leading reason is that we need to maintain healthy relationships between our libraries and our communities as we adapt to change. Actually, these are relationships between us as librarians and our communities. We owe it to our communities to engage in honest and forthright communication. If we fail to communicate about how we’re navigating technological change, our communities will think that we are blithely unaware of reality. I would argue that librarians, not books, are the heart of the library enterprise. Hiding is not an option if we want to do our jobs with excellence.

Another reason to communicate our strategies for print library collections is to work in the spirit of assessment. How well are our strategies working to achieve our outcomes? We need to be open, of course, to the possibility that our print collections are not serving their intended purposes. By articulating our purpose and our strategies for getting there, we can see how well it is going. We can’t say that something is not working without testing that assumption with data.

Finally, articulating our strategies is a way to secure investment in the library. If our constituents understand why we’re approaching change with a mix of tradition and innovation, they will hopefully be more apt to invest in our libraries.

The Why

There is something of special beauty in “dead tree books.” Some time back, I saw a cartoon that I’ve been unable to locate again. It was an image of an “antiquarian e-book dealer.” His “store” was a bucket of flash drives.

I’ve sometimes said that print books will be less like typewriters after the invention of the personal computer and more like horses after the car. Print books are already becoming a higher-end accessory because they are beautiful and valuable in their own right; they are not simply valuable for their practical utility. So our articulation of the reasons for print collections probably needs to combine some of the remaining practical utility for print as well as this sense of print books as something higher end.

In my own institutional context, the reasons to continue to collect (at least partially) in print boiled down to four key constellations.

Increasing access to resources

Print collections enable us to purchase things that are not available electronically. This is still a significant chunk of resources in theology/religion areas.

The same titles are usually less expensive in print than are the electronic library versions. Collecting in print allows us to maximize our collection breadth and stretch our dollars further.

Owning versus licensing

Print collections are “owned” rather than “licensed.” This means that “first sale doctrine” applies, so we can sell them, digitize them within the bounds of copyright/fair use, and share them with other libraries in our network on interlibrary loan.

Licensed collections give publishers and ebook vendors ultimate control over access. Licensed books can be removed from the platforms at publishers’ discretion. This has significant implications for intellectual freedom.

Marketing AMBS distinctives

We have invested in excellent space for our physical library, which is a marketing tool for attracting new campus students.

Cutting our budget for print collection purchases sends mixed messages about our investment in this asset that provides a special service experience for persons on campus.

As other small seminaries increasingly gut their physical library collections, we have become distinctive in having excellent collections both in print and online. This is something to celebrate and advertise rather than following the pack.

Research shows

The California Digital Library completed research in 2015 comparing print and electronic text experiences (“Assessing E-Book and Print Book User Behavior in Academic Libraries,” n.d.).

Key findings included: access restrictions and usability challenges can make ebooks frustrating, reading online may cause physical discomfort, learning experiences are better with print books, ebooks provide annotation alternatives, multi-tasking is easier with ebooks, deep reading is more convenient with print books, recursive reading is better supported by print books.

There are other possible constellations I might mention if I were re-doing this today. One important one for our seminary is sustainability: for financial, ecological, and human reasons (to borrow the “people-planet-profits” model). Financially speaking, we get more “bang for our buck” with print books by making a long-term investment; and we can also share them with other libraries in a way that we’re not usually permitted to share our ebooks, meaning we don’t need to acquire as many titles. Ecologically speaking, while all types of library materials use natural resources, print books are generally produced from a renewable resource (trees), and the bits and bytes of ebooks are generally run on nonrenewable and carbon-emitting coal power. And in terms of the human element, print books might be more enjoyable for staff to work with—they can feel a sense of accomplishment in cataloging and shelving—and they are generally more usable for patrons as shown in the research.

Another constellation I could mention is the sense of community built around print books. Typically, online reading is a very solitary exercise, more so even than print reading. By using shared spaces to read and sharing book collections within a community, libraries build strong and resilient communities with common reading interests and bodies of knowledge. Often, we blame social media for the political and religious balkanization and polarization here in the United States, but perhaps the issue is broader in terms of the solitary nature of online reading and online information seeking.

Communicating the Why

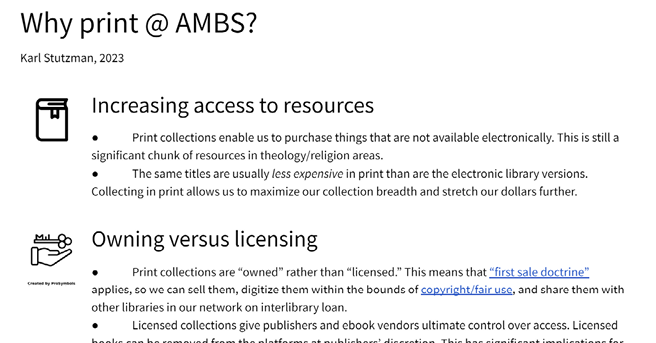

I worked at developing a single sheet that would convey these most important reasons.

This started out for me as a simple handout to attach to our budget proposal. I wanted to let my seminary’s Chief Financial Officer know why our print book budget line was important, and why I couldn’t simply take away those funds to pay for increasing database costs. So, this was part of an ask for a very modest budget increase.

Then, I brought the handout back as part of our annual assessment process. It was a handy reminder of our strategy with collections, and it was a starting point for some assessment of whether our strategy was working. We pulled data on the numbers of print books and ebooks we had acquired along with the cost for each format. We discovered—surprise surprise!—that while we spent about half of the individually purchased book collection budget on print and the other half on ebooks, we were acquiring far more print content. Of course, that does not count the presence of subscription ebook collections that come cheap, but those are not always aligned with our collection needs and instead serve as supplemental or consortial collections. So, we were stretching our dollars further by purchasing print. Of course, there are other elements of this strategy that we could and should test, such as our own students’ preferences for reading.

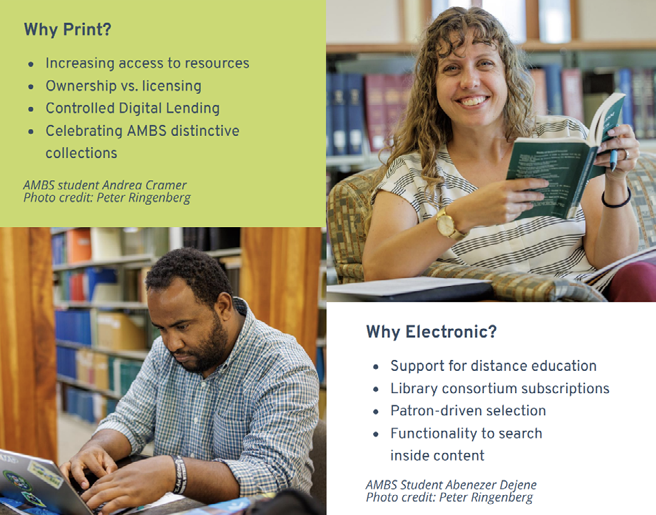

Finally, I had a brainwave to turn some of the data from our annual assessment report that I submitted to the dean into a graphical version that could reach a broader audience. This is what it looks like (see image 3), and you’ll notice that our reasons for print feature prominently here. We added reasons for electronic collections as well and displayed some of the graphs showing our strategic acquisitions.

I am not a graphic designer, but I wanted to do my best to make something attractive. To make things presentable, I made sure to use institutional font and heading styles. Our marketing department has a style guide that is very handy. In my first handout, I used icons from the Noun Project as a way to make a simple yet accessible design (“Noun Project: Free Icons & Stock Photos for Everything,” n.d.).

On the graphical report, I need to give credit to Molly Reed of Private Academic Library Network of Indiana (PALNI), which is the consortium of smaller academic libraries in our state. Molly helped me by building an annual report template in Canva, which is easy-to-use online design software. Molly made sure to use AMBS fonts, colors, etc. Canva allows us to manipulate the same content into a variety of types of presentation. It also enables us to recycle elements for future years (“Canva,” n.d.).

Results

I’m grateful for a foundation of excellent support for our library among our stakeholders.

This communication resulted in several things at AMBS. Our library got that small collections budget increase we requested. Our dean included our annual report in her report to the board. I received some comments from board members who understood our collection strategy. Finally, I have felt more confident in my “elevator speech” about why I still care about print books.

My results definitely exceeded my expectations. I hope that there will be positive results for other theology and religion librarians as well.

References

“Assessing E-Book and Print Book User Behavior in Academic Libraries.” n.d. California Digital Library. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://cdlib.org/services/collections/licensed/projects-pilots-and-studies/assessing-e-book-and-print-book-user-behavior-in-academic-libraries/.

“Canva.” n.d. Canva. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www.canva.com/.

“Library | Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary.” n.d. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www.ambs.edu/library/.

“Noun Project: Free Icons & Stock Photos for Everything.” n.d. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://thenounproject.com/.