Lessons Learned in Setting Up Atla’s New Online Institutional Repository (ir.atla.com)

Abstract: In 2023, Atla launched a new online, open access Institutional Repository (IR) for theological schools (ir.atla.com). In this Listen & Learn session, audience members had the opportunity to learn about this IR platform and IRs in general from the librarian who manages Atla’s IR, as well as two library directors who have used Atla’s platform to build electronic theses and dissertations (ETD) repositories for their institutions. Christy Karpinski, the Atla Digital Initiatives Librarian, provided an overview of Atla’s IR platform and its capabilities. Yasmine Abou-El-Kheir and John Dechant (Library Directors at the Chicago Theological Seminary and Meadville Lombard Theological School, respectively) detailed their experiences in subscribing to the platform and using it to advance their schools’ institutional goals and mission statements. The three presenters showed how Atla’s IR looks and functions, as well as how it can improve the impact of students’ scholarship and the visibility of the institution. Audience members learned strategies for successfully proposing an IR to school leaders and gained insights into different workflows for building and maintaining an ETD program.

Overview of Institutional Repositories and the Atla IR

Christy Karpinski, Digital Initiatives Librarian, Atla

“An institutional repository is an archive for collecting, preserving, and disseminating digital copies of the intellectual output of an institution, particularly a research institution”

(Wikipedia 2024)

What type of content is included in an institutional repository?

- Monographs

- Eprints of academic journal articles

- Theses

- Dissertations

- Datasets

- Administrative documents

- Course notes

- Learning objects

- Conference proceedings

- Conference slides

- Video lectures

- Student research

- Working papers

- Technical reports

- Computer software

- Photographs

- Videos

The purpose of an IR is typically to provide open access to research and other content from a single location and sometimes to provide archiving and preservation. The Atla IR has a landing page (ir.atla.com) showcasing the participating libraries’ individual repositories and a “shared search” that allows users to search across all the repositories. Each library has its own “tenant” and a unique URL. Two examples are Chicago Theological Seminary (https://ctschicago.ir.atla.com) and Meadville Lombard Theological School (https://meadville.ir.atla.com/).

The Atla IR can handle most file types. It displays images, audio, and video in the IIIF Universal Viewer and displays PDFs using PDF.js. The PDF viewer allows full-text searching. Video can also be displayed with embedded URLs from YouTube and Vimeo.

Works can be added using one of four work types: General, Image, ETD, Paper or Report. These work types determine the metadata fields that are available for the work. You can also use embargoes and leases and limit the visibility of works.

Works can be added individually or in bulk through the user interface. Bulk importing can be done through CSV, OAI-PMH, XML, and Bagit. Bulk exporting can also be performed. These capabilities can be used to make updates to works in bulk or to export to use with a preservation service.

There are many ways to customize an individual repository in the Atla IR. These include themes for home and work pages, custom CSS, banner images, icons, fonts, and logos. You can also customize the about and help pages, deposit agreement, and terms of use.

CTS Digital Commons

Yasmine Abou-El-Kheir, Director, Lapp Learning Commons, Chicago Theological Seminary

Established in the boomtown of Chicago in 1855, the Chicago Theological Seminary’s first mission was to train church leaders on what was then America’s western boundary. Throughout our history, CTS has been a leader in theological education, social justice, and societal transformation. As a stand-alone seminary, CTS currently offers a PhD program, six online MA-level programs, and a new fully online DMin program. Our students are almost all online; as such, there is a high expectation that they can access the information they need for their studies online as well.

Why Develop an ETD at CTS?

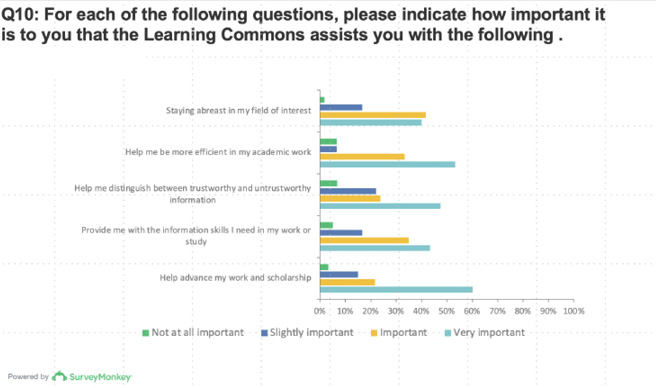

The need for an institutional repository at CTS was first identified in the Learning Commons’ needs assessment conducted in 2014 (which corresponds to our pivot to a fully online MDiv degree in 2013) and then again in 2023. In the recent 2023 survey, the CTS community overwhelmingly prioritized the importance of the Learning Commons in advancing their work and scholarship (see figure 2). The importance accorded to this service far surpassed other services, such as: staying abreast in their field of interest; becoming efficient in academic work; distinguishing between trustworthy and untrustworthy information; and developing information skill needed for their work.

Anecdotally, the importance of disseminating research is also in evidence when CTS students describe their bound thesis or dissertation as being “published.” This misperception can be understood as an indicator of students wanting greater visibility for their work. This desire is further explicitly communicated with regular requests from students wanting to make their work available online through commercial services like Proquest’s ETD service. While such services can make student work discoverable, they do raise the question of equitable revenue sharing for student work given the existing royalties fee structure. With the move to an open access ETD program facilitated by Atla’s IR service, it is the students who are the primary participants and beneficiaries (Rasuli, Solaimani, and Alipour-Hafezi 2019). Furthermore, developing an open access IR can raise the visibility of CTS as an institution with the broader dissemination of CTS student work. Theses and dissertations are, after all, direct products of our degree programs and can be viewed as institutional assets.

Pedagogically, implementing an IR at CTS aligns well with many of ACRL’s information literacy frames (Association of College and Research Libraries 2024). ETD repositories can showcase how CTS students create and disseminate original research and they illustrate the iterative nature of scholarly work. Students also learn to format and structure their thesis/dissertation according to academic standards. In other words, the Information Creation as a Process frame in ACRL’s framework.

Students who search IRs can find research projects that demonstrate how scholars in their field formulate questions, select appropriate research methods and develop conclusions. This aligns with the Research as Inquiry frame and its focus on research as an open-ended exploration. By making theses and dissertations openly accessible, IRs allow graduate students to contribute their voices to ongoing scholarly dialogues. This supports the frame of Scholarship as a Conversation among researchers. Another goal for developing an open access IR is for participating students to gain firsthand experience with issues of intellectual property, privacy, copyright, and open access which lends well to the Information has Value frame.

By developing an ETD program at CTS, graduate students develop crucial information literacy skills that prepare them for future roles as researchers and scholars. Repositories serve as both a practical tool for disseminating research and an educational platform for developing information literacy competencies aligned with the ACRL frames. Repositories also function as a unique genre of scholarly communication that can help advance graduate humanities education and research (Shirazi and Zweibel 2020).

Setting up CTS Digital Commons

The Learning Commons has about 2,000 theses and dissertations dating back to 1895. The collection is non-circulating, with the bulk held in the basement compact storage area. On average we field 10–15 scan requests per year. While this number of scans may seem small, the opportunity to build an ETD moves Learning Commons from being the “custodian” of physical copies, with our librarians serving as access intermediaries, to the library and librarians as facilitators of unmediated digital scholarly communication that is accessible to all (Yiotis 2008).

The Learning Commons has a small staff with 1.5 FTE staff. It is important to note our small staff size because we would not have been able to establish an ETD program without Atla’s extensive documentation for the IR, and more importantly, support from Atla’s staff. They played an instrumental role in fielding our questions and helping us troubleshoot issues as they emerged. We found the interface easy to use and required few customizations. Prior to selecting Atla’s IR for CTS’ ETD platform, we did look into Open Repository and Lyrasis’ DSpace as potential service providers. We found that Atla’s IR program offered us an opportunity to set-up an ETD for a fraction of the cost.

Implementing the CTS Digital Commons at CTS also provided the Learning Commons and degree programs supervisors and other stakeholders with an opportunity to rethink the thesis and dissertation submission process. In the past, students submitted their final thesis or dissertations directly to their advisors. The introduction of the IR allowed for us to integrate processes such as communications around graduation requirements, upcoming graduation deadlines and format and citation review. The Learning Commons worked alongside the Registrar’s Office, the director of Online Learning, MA/STM advisor and the Academic Dean to not only develop this new workflow but make it a requirement for students to deposit their work in the CTS Digital Commons prior to graduation. Students who did not deposit a physical and electronic copy of their work could have their diplomas withheld until they did so.

A student submission portal was created in Canvas with graduating students enrolled in the Capstone Submissions Course. Academic advisors were enrolled and assigned the students they were supervising. The Language and Writing Center coordinator was also enrolled in the course. Four modules were developed. One module was for students to submit their work to faculty and for thesis/format review by the Language and Writing Center. This module included information about format and citation requirements for each degree program. The second module provided information about CTS Digital Commons that outlined the benefits of contributing student scholarly works to the IR, as well as instructions on how to deposit their work. The third module provided information on how to submit their printed thesis/dissertation to the Learning Commons. The fourth module provided additional information regarding graduation requirements and deadlines for CTS. This structure made it possible for student submissions to be viewed by faculty advisors as well as the Language and Writing Center coordinator at the time of submission. This approach helped keep the review process in one place and alleviated the previous challenge of chasing down students and getting them to submit their theses/dissertations for format and citation review prior to the defense (and sometimes well after the defense!).

Year One Lessons Learned

To date, we have had about 27 projects submitted in our inaugural year, accounting for all of our 20 graduating MA, DMin and PhD students in 2024 and another 7 projects from the previous year that we used to seed the platform. Moving forward, we will continue to keep the thesis and dissertation submission and review process in Canvas. This change in our workflow proved to be an efficient way for various departments at CTS to be aware of where students were in their submission process. Faculty advisors had one place to keep track of their advisees, the Language and Writing Center had immediate access to student work to review for format and citation, and the Learning Commons could send reminders to students within the course about upcoming deadlines regarding electronic submission of final, corrected work to CTS Digital Commons and physical deposit in the Learning Commons.

Our experience with this new submission process was not without its problems. We did learn about the critical importance of multi-channel communication. It is not enough to have information posted in Canvas and emailed/messaged to students to address questions and concerns students may have. As a mostly online educational institution, we rely a lot on written communication. We found that while all our students deposited their projects, very few opted to make their work visible to the public. When we set-up the IR we allowed for students to select one of four visibility settings: public (accessible to all), institution (accessible to CTS community members), private (accessible to the student only) or embargo. The majority of our students selected either the private or institution visibility setting. This puzzled us given earlier student feedback in surveys and focus groups about the importance of the Learning Commons in disseminating their scholarly works (see image 2).

It is only through face-to-face conversations with students during commencement week that we heard their concerns. Many were apprehensive about their work being appropriated by others if they set their work to a publicly available setting. This discovery revealed a missed opportunity for the Learning Commons to highlight the CTS Digital Commons as a hub for scholarly communication that copyrights and protects their work at the moment of submission. Enhancing information literacy as they relate to ETDs was another opportunity missed. Although the information posted in Canvas and in the FAQs on the CTS Digital Commons site clearly stated that students retain copyright to their works, this written assurance was not enough. Students needed the space to question this assertion and express their concerns.

At a post-graduation follow-up meeting with the Academic Dean and MA/STM thesis course advisors, this issue around student copyright concerns was raised. We agreed on the need to tackle this concern at the graduation requirements meeting held for graduation students early in the Spring semester; and to invite the librarian back in the Spring to the MA/STM Thesis Seminar to cover thesis submission requirements and address questions and concerns at a time when students were ready to receive this information, rather than simply in the Fall when it’s not on their radar. This latter point contributed to a more robust conversation around the various ways librarians can be embedded in the MA/STM Seminar course. Finally, we discussed the possibility of limiting ETD visibility options for MA/STM students, and only allowing PhD and DMin students to do so.

Overall, implementing CTS Digital Commons with Atla’s IR service presented itself as an opportunity for CTS to not only disseminate student work and raise the profile of the institution. It provided an opportunity as well to rethink how the various parts of the seminary coordinate with one another and facilitate the final stage of a student’s seminary experience. Important questions around workflows, pedagogy and student engagement were explored. Hopefully, Year Two will provide further avenues for such discussions made possible, in large part, because of the introduction of CTS Digital Commons as a scholarly hub at CTS.

Melodic, the Meadville Lombard Digital Commons

John Dechant, Director of Library & Archives, Meadville Lombard Theological School

Chicago-based Meadville Lombard Theological School (hereafter MLTS) is one of only two active Unitarian Universalist-affiliated seminaries. Originally founded as the Meadville Theological School in Meadville, Pennsylvania in 1844, MLTS has a long history of students producing dissertations, theses, and capstone projects. Since 2011, the school has followed a contextual model of education, in which students take online classes while continuing to live and work in their local congregations and communities around the United States and the world. Students mainly come to the physical library—the Wiggin Library—twice a year during the once-a-semester all-but-required in-person intensive week in Chicago. Despite the largely online course model, the thesis/project submission process up until 2023 involved printing and binding such works and adding them to our non-circulating collection. There was not even a publicly accessible inventory of what capstone works we had available. Given that students were rarely in person on campus and most archival patrons access the Archives online, hardly anyone in recent years had read or accessed MLTS’s almost 180-year print collection of theses, dissertations, and projects.

As the incoming Director of Library & Archives, the above facts convinced me that MLTS would benefit from an IR. I consulted the relevant MLTS stakeholders to make sure they were on board. In particular, MLTS had just launched a new DMin program in Social Justice, and the DMin Director was keen on ways to promote the new program and showcase her students’ upcoming projects. Given that establishing an ETD program would involve revising our thesis/project submission process, the interim Academic Dean requested that the proposal be approved before an all-faculty meeting. Before the meeting, I put together and distributed a white paper (Dechant 2023). Avoiding or explaining LIS jargon, I made the case that MLTS—both the institution and its students—would benefit from adopting an ETD program:

- MLTS student theses, dissertations, and projects are not easily accessible and rarely accessed because they are only available in print and are non-circulating, and because the bulk of our library and archival patron interactions occur online.

- Adopting an IR can help us streamline our thesis/project submission process and better ensure that students were submitting their works according to our house style, The Chicago Manual of Style. Some recently bound works, for example, lacked page numbers and dates, while one work was a xeroxed copy of an earlier draft, complete with the advisor’s handwritten notes!

- Many of our peer theological institutions already have an IR.

- Theses, dissertations, and projects available via open access are much more likely to be read than such works available only in print. This will better demonstrate MLTS students’ achievements, expand the impact of their scholarship, and increase our institutional visibility (Nolan and Costanza 2006, 97; Bergin and Roh 2016, 136-137; Bruns and Inefuku 2016, 215-216).

- An ETD program that promotes open access would align with MLTS’s institutional values:

- Publishing, including publishing on a formal, accessibility-oriented platform like an IR, can add an air of authority to our students’ works (Borgman 2007, 48-49), helping with our institutional value of “Integrating scholarly excellence in theological education” (Meadville Lombard Theological School n.d.).

- Job-seeking MLTS graduates can more easily direct potential employers to their academic work, helping our students achieve the congregational and community leadership roles for which MLTS trains them.

- Given that our students research and write projects and theses that challenge white privilege, advocate gender justice, celebrate the LGBTQ+ community, champion diversity, and more, making their work more publicly available can only advance our own institutional progressive values.

- Since MLTS values “Reshaping and reforming tradition to impel innovative ministries” (Meadville Lombard Theological School n.d.), it makes sense to reshape and reform how students submit and make available their theses and projects in the digital age.

- IRs are not a passing fad; they have been around for more than twenty years and scholars have demonstrated their effectiveness (Rieh, et al. 2007, 1–8).

Concerns about copyright protection were also addressed in the white paper. The student-author retains copyright of their work after they submit it, whether it is uploaded to the IR or just printed. By submitting their work to the IR, the student only grants to the institution the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible their work under the conditions they select in their deposit form. While it is commonly believed that open access prevents an author from publishing some or all of their work as a book or article, two studies have shown that most academic publishers have no problem publishing an article or book that was based on a work available in an IR (Ramirez et al. 2013, 368–370, 372–377; McMillan 2016, 111–112, 116–120). Most academic publishers almost never agree to directly publish a student thesis or dissertation without significant revision, making the final book or article a different work than what is in the repository. All scholarship builds on earlier scholarship, including the author’s earlier scholarship. In this case, the book or article they would publish is based, in part, on the student’s earlier project/thesis. Nonetheless, a good ETD repository, including Atla’s IR, allows institutions to set embargo policies and allows submitters who are concerned that open access publication may hinder future publication to select an embargo or a more restricted Institutional or Private access.

Finally, the white paper compared and contrasted Atla’s IR versus other options. While it is possible to build an ETD repository from scratch—as there are several free, open-source software platforms to choose from—it would cost too much in terms of labor hours for our small (FTE 2) staff of librarians to set up and manage. On the other end, I presented quotes from other companies that manage IR platforms, but that would cost substantially more than Atla’s. In support of Atla’s IR, I noted that a colleague whose similarly small-sized theological library had adopted the same Hyku platform that Atla was proposing for their IR had nothing but high praise for how easy it worked. Building our ETD repository through Atla’s IR also offered the prospect of greater discoverability, as patrons searching for theological works from another collection on Atla’s IR would be more likely to come across our works.

Having obtained administration and faculty support and buy-in, MLTS adopted Atla’s IR in late summer 2023. The platform was relatively easy to set up. Atla provided a template for a deposit agreement that made filling in our institution’s name easy. Christy Karpinski, Atla’s Digital Initiatives Librarian, provided a helpful user guide and responded to questions quickly and effectively. The only particular downside to Atla’s IR has been that, unlike some other more expensive options, Atla’s IR as it currently stands cannot guarantee long term preservation of digital works uploaded onto the platform, as it does not involve the more advanced aspects of digital preservation (extensive geographic redundancy, fixity checks, etc.). To put it another way, Atla’s IR is currently an accessibility solution, not a long-term digital preservation solution. We at MLTS have managed this by retaining separate copies of all works on MLTS’s secure internal server. Uploading a work on the IR nonetheless still functions as putting another egg in one more basket.

For branding, MLTS employs a part-time graphic designer who provided the website with a beautiful banner and a set of favicons. I was concerned that patrons would have a hard time remembering the IR’s URL (meadville.ir.atla.com), as the acronym IR is not common knowledge amongst the general public, nor is Atla (sadly!) well known beyond the theological library profession; when I also realized that Melodic is a much more memorable acronym for MEadville LOmbard DIgital Commons, we rechristened our IR “Melodic,” and created the URL of meadville.edu/melodic to redirect the user to meadville.ir.atla.com. The faculty and administration have found meadville.edu/melodic much easier to remember and are therefore better able to direct others to the website.

As a small institution, it would take years to populate the IR with only newly submitted works and make the costs worthwhile. Using the deposit agreement provided by Atla as a foundation, we drafted a deposit agreement for alumni and contacted them to request their permission to digitize and post their works on Melodic, adding that agreeing to do so was their decision, but that it would help their alma mater. More than a quarter of the alumni contacted responded, and almost all the responders enthusiastically granted their permission for public, open access publication. We also began digitizing and posting theses, dissertations, and projects that were out of copyright. We focused on digitizing and posting works from before 1923, including our extensive collection of hand-written student papers from the “Philanthropic Society” (Meadville Theological School’s nineteenth-century debate club) and “Anniversary Exercise” essays that were delivered aloud at the precursor to MLTS’s graduation ceremony, the Anniversary Exercises, from 1845 to the early twentieth century. These collections help support our narrative that MLTS has a long history of producing progressive theological scholarship. For more recent out-of-copyright works where the author is still alive, we have tried to respect and obtain the author’s permission before posting their work, although we have kept the language of our request and agreement open to pursue posting such works if we do not receive any response to repeated requests.

Overall, I have found subscribing to Atla’s IR one of the best decisions I have made as a new Library Director. It has helped us to modernize and advertise our institution. In adopting and managing an ETD repository, the library is now a more integral part of the thesis/project submission process. Previously, the library facilitated the printing and binding of two copies of each thesis or project—one for the library, the other for the student—and billed the students for the costs. Instead, we now spend that time engaged in information literacy work by ensuring that works adhere to Chicago Style and explaining copyright issues. Graduates like that they are no longer receiving one final bill for a printed copy that is not theirs. For students still interested in obtaining a printed and bound copy, we now direct them on how to obtain one themselves (for less money) via the Thesis on Demand company. In the future, we aim to continue expanding our collection of historical works. As Yasmine Abou-El-Kheir explained above, we have also found that graduating students need to be better informed of how open access can benefit them. The silver lining to the problem is that we are information literacy professionals, and because of our new thesis and project submission process, we have identified a new opportunity to better instruct our students on issues of copyright and scholarly communication.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2024. “Scholarly Communication Toolkit: Repositories.” https://acrl.libguides.com/scholcomm/toolkit/repositories.

Bergin, Meghan Banach, and Charlotte Roh. 2016. “Systematically Populating an IR With ETDs: Launching a Retrospective Digitization Project and Collecting Current ETDs.” In Making Institutional Repositories Work, edited by Burton B. Callicott, David Scherer, and Andrew Wesolek, 127–138. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1wf4drg.14.

Borgman, C. L. 2007. Scholarship in the Digital Age: Information, Infrastructure, and the Internet. Boston: MIT Press.

Bruns, Todd and Harrison W. Inefuku. 2016. “Purposeful Metrics: Matching Institutional Repository Metrics to Purpose and Audience.” In Making Institutional Repositories Work, edited by Burton B. Callicott, David Scherer, and Andrew Wesolek, 212–234. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1wf4drg.21.

Dechant, John. 2023. “A Proposal for the Adoption of an Open Access ETD.” Unpublished white paper. Chicago: Meadville Lombard Theological School.

McMillan, Gail. 2016. “Electronic Theses and Dissertations: Preparing Graduate Students for Their Futures.” In Making Institutional Repositories Work, edited by Burton B. Callicott, David Scherer, and Andrew Wesolek, 107–126. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1wf4drg.13.

Meadville Lombard Theological School. n.d. “About Our School.” Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.meadville.edu/who-we-are/about-our-school/.

Nolan, Christopher W., and Jane Costanza. 2006. “Promoting and Archiving Student Work through an Institutional Repository: Trinity University, LASR, and the Digital Commons,” Serials Review 32 (2): 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2006.10765038.

Ramirez, Marisa L., Joan T. Dalton, Gail McMillan, Max Read, and Nancy H. Seamans. 2013. “Do Open Access Electronic Theses and Dissertations Diminish Publishing Opportunities in the Social Sciences and Humanities? Findings from a 2011 Survey of Academic Publishers.” College & Research Libraries 74 (4): 368–380. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-356.

Rasuli, Behrooz, Sam Solaimani, and Mehdi Alipour-Hafezi. 2019. “Electronic Theses and Dissertations Programs: A Review of the Critical Success Factors.” College & Research Libraries, 80 (1). https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16924/19367.

Rieh, Soo Young, Karen Markey, Elizabeth Yakel, Beth St. Jean, and Jihyun Kim. 2007. “Perceived Values and Benefits of Institutional Repositories: A Perspective of Digital Curation.” Working paper, School of Information, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. https://ils.unc.edu/digccurr2007/papers/rieh_paper_6-2.pdf.

Shirazi, Roxanne, and Stephen Zweibel. 2020. “Documenting Digital Projects: Instituting Guidelines for Digital Dissertations and Theses in the Humanities.” College & Research Libraries, 81 (7). https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/24674/32494.

Wikipedia. 2024. “Institutional repository.” Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified June 1, 2024, 05:18. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutional_repository.

Yiotis, Kristen. 2008. “Electronic Theses and Dissertation (ETD) Repositories: What are They? Where do they Come From? How do they Work?” OCLC Systems & Services: International Digital Library Perspectives, 24 (2): 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650750810875458.