Artful Response to Scriptures

Abstract: Art has long been part of sacred texts in many religious faiths, notably as decorative, stylized, and illuminated calligraphy. How scripture was presented aesthetically carried sacred significance. In modern times, it is common to leave artistic expression of scripture to either paid professionals or children—but writing, illustrating, or artistically responding to scripture can be a devotional practice available to anyone. This paper discusses ways to recover creatively engaging with sacred texts as inspiration and medium, provides examples of creative spiritual engagement in practice, and discusses ways to engage students through related active and passive programming. Session attendees were given time and supplies for the practice of creative spiritual engagement and to share their experience of it. The session was accessible to a variety of religious traditions by allowing participants to choose their own sacred text with which to work.

Introduction

Sacred texts throughout time have often been made beautiful. Across faith traditions, it seems there was a recognized spiritual significance to presenting scriptures artistically. Recently, there has been a renewed interest in making creative expression part of engagement with faith for everyone. Such practices can benefit students at our institutions, particularly those participating in spiritually challenging activities, like nursing clinicals or pastoral internships. Contemplative creative expression can be an excellent addition to library programming, both active and passive, meeting a real need for student communities and acting as a form of student outreach that grows on activities that are already common in library spaces.

Karl Stutzman, Director of Library Services, Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary

My inspiration for this session came from a Biblical Spirituality course I took several years ago at our seminary. One of the spiritual practices we learned was a form of artful response to Scripture. In my journey since then toward greater mental health, engagement with art and faith has been really important. I think that we as librarians have an important role in our institutions—we have a vocation to teach students to research, read, and write effectively, and part of this means engaging with texts in creative ways. I also have a strong interest in interfaith engagement. This has been an important aspect of Atla for me, and I’m interested in finding ways for us all to engage our diverse spiritualities together in this community. I hope that these practices of artful response to scripture provide a way that we can build a strong multifaith community.

Jude Morrissey, Access Services Librarian, Yale University Divinity School

In my own spiritual life, as a person with ADHD, I have found faithful creative expression to be powerful. Having something to do with my hands always helps me to concentrate; but making something related to the Scripture I am studying or the practice in which I am engaging deepens the experience and often leads me to new insights or a feeling of greater connection. I have used book art, photography, creative writing, and automatic drawing in my own devotional practices. I also create Anglican prayer beads while I pray, most of which I set out for students to take during midterms and finals or give to students beginning clinical pastoral education placements. As passive programming in the past, I have put together kits with instructions for making Anglican prayer beads and am currently planning a workshop for book art as spiritual practice.

Sacred Text and Art

In many medieval Christian manuscripts, such as books of hours, the first letter of a prayer, Scripture, or other text was decorated with illustrations meant to suggest stories that would, with the help of their captions, be illuminated by the text itself. The historiated capital for Psalm 120 in the de Brailes Book of Hours (see figure 1) shows the Virgin Mary punching the devil in the nose—an illustration from the legend of Theophilus, whose soul is saved from damnation by Mary’s intervention (Donovan 1991, 40). While reciting the Psalm, the reader is meant to consider the story presented in the artwork and draw spiritual insight or guidance from the experience.

In several faith traditions, the art of the text matters, as with the historiated capital. The lettering is not entirely decorative, but its beauty is important. For Christianity, as one of the “religions of the word,” like Judaism and Islam, writing itself is often considered to be invested with spiritual force and thus becomes Scripture. Just as the Word becomes visible in Christ Incarnate, the text of Scripture written down participates both in the spiritual realm and the physical. Decorative or illuminated text can be transformed and transformative, the visualized word not just communicating meaning but creating space for meditation and contemplation (Hamburger 2014, 6–8).

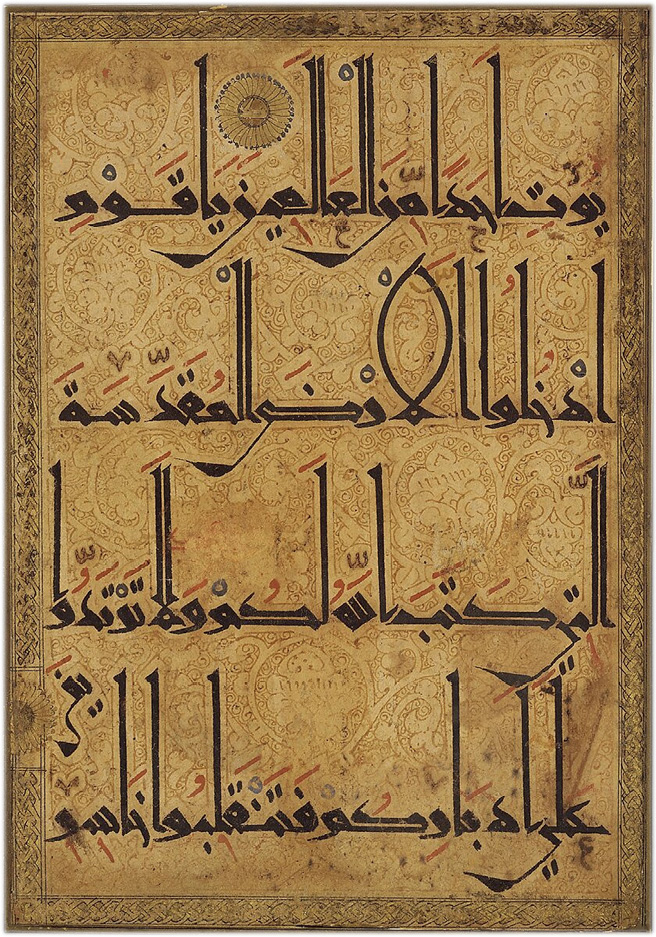

In Islam, too, writing is understood to be a way of manifesting the word of the Qur’an—and so calligraphy has risen to be the highest art, because it makes visible the message of the invisible God (Rahman 2004, 31). Often, Islamic calligraphy is highly decorative, in the formation of the letters themselves (see figure 2) or by making geometric, zoomorphic, or other shapes with writing (Schimmel 2004, 17).

For Judaism, studying the Torah is vital for spiritual development, but the call to study comes with a second call to write the words. In mystical Jewish traditions, it isn’t just the content of the text that carries meaning—the shapes of the letters have holy meanings (Pludwinski 2012, 4).

In many Eastern religions, writing is considered a gift from the gods (Stevens 1981, xi). In Hinduism, copying the alphabet becomes an act of worship, and each letter is an object of contemplation (Stevens 1981, 18). With all the spiritual meaning inherent in creative engagement in the written word, it may not be surprising that we tend to leave scriptural art to specially trained or professional artists, although we let children play with the words a bit, in Sunday school and the like.

Figure 2: Folio from a Qur’an manuscript, ca. 1180 CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.160.23

Figure 2: Folio from a Qur’an manuscript, ca. 1180 CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.160.23Modern Devotional Movements

Recently, however, there have been movements in multiple faith traditions to encourage everyone to engage in art as spiritual practice. Carmelle Beaugelin Caldwell, founder of BeauFolio Studio, leads workshops combining the Christian practice of lectio divina with guided sacred art-making: creatio divina (https://beaufoliostudio.com/creatiodivina). The process of CreatioDivina consists of five steps, labeled The Breath, The Invitation, The Creation, The Examination, and The Ask.

Rabbi Adina Allen brought together the Open Studio Process (an art therapy practice) with the Jewish practice of beit midrash to create the Jewish Studio Process, which is taught through the Jewish Studio Project as a practice to build spiritual connection and enact social transformation (https://www.jewishstudioproject.org/the-jewish-studio-process). The Jewish Studio Process follows the steps of Inquiry, Intention, Creative Exploration, and Reflection.

The Sacred Art Academy offers courses and workshops that teach Islam through art, including calligraphy (https://www.sacredartacademy.com/). Jayni Roxton-Wiggill, the owner and operator of Aura.Soul.Art who practices a form of Jungian spirituality, offers SoulFull Art workshops to lead participants to connect with their authentic selves for a fuller emotional and spiritual life (https://www.aurasoulart.com/art-full). This process includes Thematic Discussion/Guided Meditation, Breathing, a Labyrinth Walk, and Spontaneous Painting.

These are just a few examples of attempts to encourage spiritual formation through creative faith engagement. There are also communities of support formed around those who see their artwork as sacred practice (see figure 3), such as Numen Arts, a collective of polytheist artists who see their work as sacred practice (https://numenarts.org/about.html).

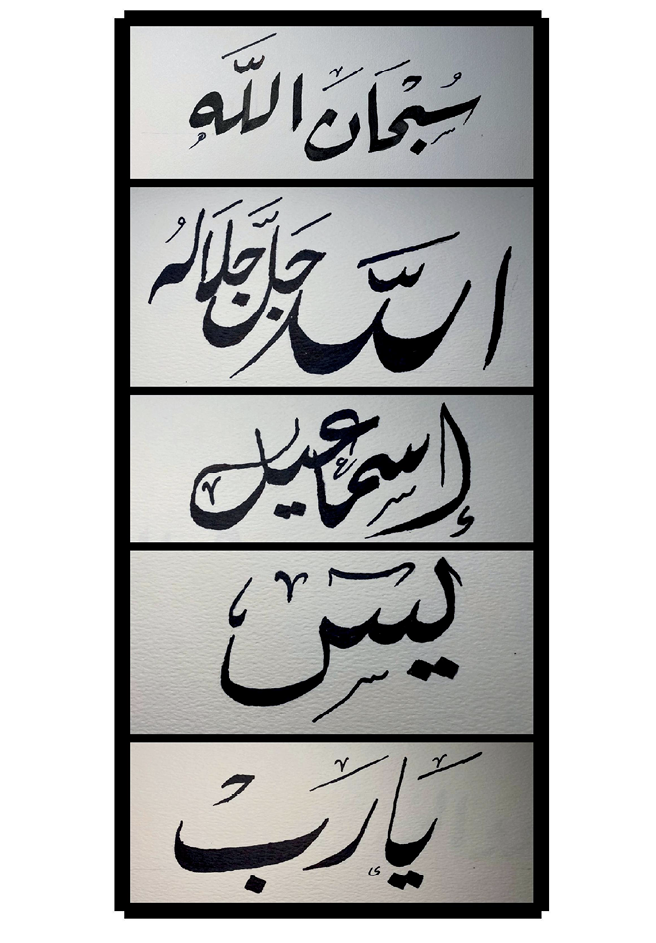

In these and similar movements, the process differs; but there are some things they have in common. For traditions that have scriptures, reading and reflecting on the words of the text or, especially in Islam, the names of God, are often central to the process. In Buddhism, chanting mantras is, too. For traditions that do not have scriptures, thematic discussion or guided meditation may be used instead. Sometimes it is the emptying of thought, as in the Christian practice of centering prayer, that forms the bridge between the spiritual and the artistic to create a new practice. Usually, making art or other creative expression is followed by a time of shared reflection: communication with God, nature, or others is important to the practice. Shared reflections are not necessarily time-bound, either, but exist within the work itself. Ahmed Ramadan who moved from Egypt to the United States and joined Yale University Library as a cataloging assistant in 2001 and who writes holy words as a spiritual practice (see figure 4) believes Arabic calligraphy is the pillar of Islamic art, communicating thoughts and meanings through its artistry across all ages.

“Creatio Divina” and Student Outreach

Libraries, particularly those connected to religious and theological institutions, are well-placed to bring the concept of spiritual engagement through creative expression, and some of the practices guiding such engagement, to their communities. Many academic libraries already participate in active or passive mental health and stress relief programming, particularly during midterms and finals. Several even put out art supplies already. Making art is good for mental and emotional health, especially during times of high stress; but making art is also good for spiritual health—particularly for “creative repair,” a term coined by Anne C. Holmes to refer to “regular, active engagement with the creative arts as a way of repairing energy expended in sensitive pastoral care” (Holmes 2023, 6). For seminary students involved in clinical pastoral education placements or internships, the practice they learn in the library could be the spiritual engagement that both serves an immediate need and provides long-term self-care in future ministry. For similar reasons, the same idea ought to hold true for religious folks studying nursing, social work, psychology, and any number of other fields where they are liable to face spiritual crises on a regular basis.

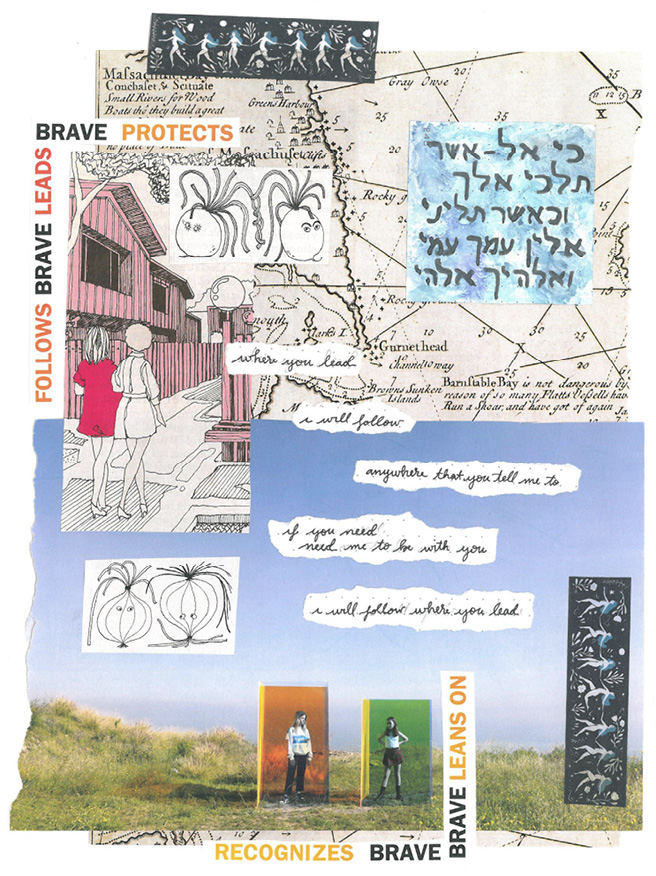

At schools where spiritual formation is a goal alongside academic formation, teaching students to engage their faith through art gives them an outlet to process their challenged and changing beliefs outside academic structures like formal papers—something that lets them feel as well as think about their living, evolving faith, something they can share without being evaluated or graded. Cliel Shdaimah, a recent graduate from Yale Divinity School and a devout Jew, notes that if she were to create today meditating on a pericope of Scripture, it would likely be very different from work she has done before on the same set of verses, because she is changing and growing and so is her understanding of the Scripture (see figure 5).

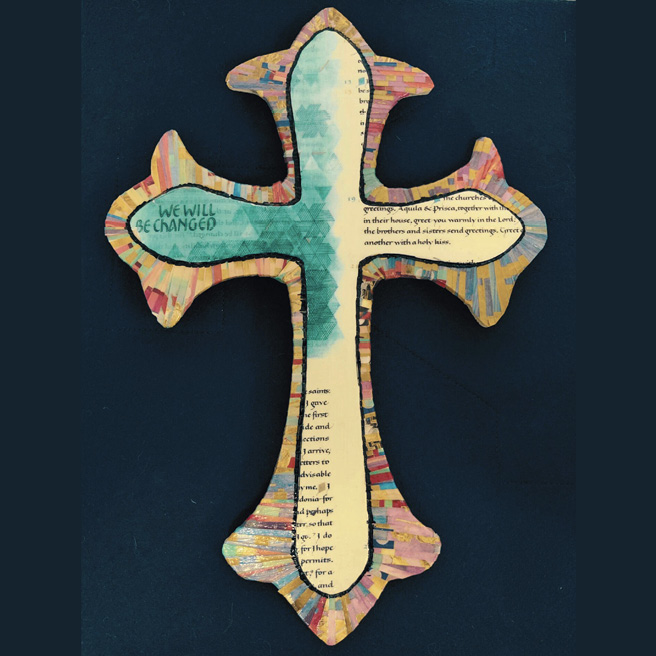

In addition, creative engagement with sacred texts can serve as an excellent gateway to interfaith discussion, particularly when different faith traditions share the same scriptures. It allows believers to show what the scripture means to them in their tradition and explore different meanings with those in different traditions. Library programming using other religious works, such as hymnals or prayer books, as the raw material for creative spiritual practices can also be a good practice for creative weeding. Milligan Libraries, where Jude worked prior to joining Yale Divinity Library, held annual Book+Art events. For these events, students were encouraged to take books that had reached the end of their shelf-lives and transform them into artwork. Creating art from worn-out books or other items can also teach students one way to honor the medium when it no longer functions as intended. Loose pages from a beloved text can be used to create wall art, paperweights, bookmarks, and more (see figure 6). Creative practices can also be combined, such as using pages of a worn family Bible to make prayer beads, which can then serve as a reminder to pray for family members.

There are several ways to reach out to students (either through active or passive programming) to encourage a practice of creative engagement with faith. Book art events, as at Milligan Libraries, can help students learn to honor the medium when it has begun to fall apart, and help them consider what can be done in their future ministries with old hymnals when it is time to replace them, instead of throwing them away or storing them indefinitely. Photography is another creative practice that can be adopted for spiritual growth—especially when a theme is introduced. Advent Word (https://adventword.org) is an annual online event where followers are asked to creatively respond to the word of the day, taken from lectionary readings; it then posts images on social media, showcasing photographs from participants around the world. Something similar, where students are asked to respond to (for example) the all-school read with a photograph and tag the library, is a very passive program.

Students can be given the supplies and opportunity to use pictures and words in combination to represent something about their spiritual identity, which can then perhaps be displayed. Pictures of their creations might be put up digitally, rotating on a monitor (to save printing costs) and students encouraged to discuss their work together. A workshop on creative journaling or prayer, incorporating doodles or decorative lettering could be offered. Likewise, a handout explaining automatic drawing or painting, where you just start making art without intentionally working towards an image to see what appears and linking it to centering prayer or other meditative practices, can help folks who don’t think of themselves as artistic begin to practice creative engagement with their faith. Sho Zuska, a Celtic neopagan, uses automatic drawing to create artwork while meditating outdoors, to connect spiritually with nature (see figure 7).

And, of course, libraries can show how calligraphy can be a creative practice of spiritual engagement with scripture. Making the words as beautiful as possible, decorating them with images from related stories or simply writing them in pleasant shapes while meditating on their meaning, can open space for spiritual contemplation. This could be a workshop, too, or it could be a display of Special Collections materials from various faiths along with a handout on the practice, encouraging students to try it for themselves.

Practicing and Sharing

Practices and methods of engaging with artful response to scriptures may vary depending on the context. The supplies and setup may be fairly simple, to avoid messes and make them generally friendly to the library environment: paper of various weights and sizes, gel pens, and colored pencils go a long way and are fairly affordable, even for a modest library budget. For a more advanced setup in a facility that allows for cleanup, materials like scissors, glue, paints, clay, and more could be appropriate. The constraints of limited supplies may allow for a particular form of creativity to emerge; creativity thrives where there are boundaries and margins.

Providing examples—particularly of less than perfect models—may be helpful to participants in setting the stage. In the conference presentation, Karl emphasized that this activity was about “process, not perfection.”

It may be helpful to encourage participants to pair this with the use of other spiritual practices, such as prayer, or lectio divina, or silence—either before or after the artful response to their chosen text. Depending on the context, it can be helpful to define scripture generously. In the Atla conference context, for example, Karl acknowledged that participants would almost certainly not have a shared canon of scripture and that this was acceptable. In other contexts, it may be valuable to draw on a shared canon or make copies of sacred texts available. At Atla Annual, participants were relied upon to choose and bring with them their own copies of sacred texts.

Once participants choose their texts and spend time in reflection, it is up to the participants to write out their own texts in an artistic way, using color, lettering styles, doodling, and drawing to illustrate their text and bring it to life. This is a fairly freeform experience, allowing each individual to bring their creativity and expression to their text.

In the Atla conference context, participants used a sharing protocol to share texts, work, and experiences with each other. This could be useful for a group doing this activity together. It may also be possible to share asynchronously using a display space or social media. The sharing protocol used in the presentation arranged the group into a circle with a “talking piece” (any object that can signify respect for the person holding it having their turn to speak). As the leader, Karl acknowledged the diversity of those present and allowed participants to pass if they did not feel led to share. Passing the talking piece around the room and allowing each individual to claim their voice if they choose to do so can be a powerful exercise in listening and building community.

At Atla Annual, participants did two rounds of sharing. In the first round, the participants were able to identify their name and the text they chose. In the second round, participants could share a brief reflection on what they observed in the time of responding to the text using art. A rule against crosstalk, or commenting on the shares of others, was instituted in order to ensure a safe space for everyone to share without fear of judgment.

Conclusion

Interactions with scripture are both deeply personal and communal. The range of expression permitted in this artful response activity allows individuals the opportunity to embody texts they consider sacred. It allows them to see how other individuals are engaging and learn from that as well. Done carefully, artful engagement with a variety of scriptures may be a way forward to building community in interfaith contexts. It may also be a source for strengthening a particular faith community from within. Libraries, as liminal spaces in the academy that mediate a long tradition of scholarship, are well-positioned to teach students and other community members the value of reading and responding to sacred texts through art. In this way, libraries can not only build individual spirituality, but also communal spirituality.

References

Donovan, Claire. 1991. The de Brailes Hours: Shaping the Book of Hours in Thirteenth-Century Oxford. London: British Library.

Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2014. Script as Image. Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts, vol. 21. Leuven: Peeters.

Holmes, Anne C. 2023. Creative Repair: Pastoral Care and Creativity. SCM Press.

Pludwinski, Izzy. 2012. Mastering Hebrew Calligraphy. New Milford, CT: Toby Press.

Rahman, Khalida. 2004. “Creative Spirit of the Traditional Art of Calligraphy, through the Contemporary Medium of Photography.” In Creativity and Crafts in the Muslim World: Proceedings of the International Seminar on Creativity in Islamic Crafts, Islamabad, 10-12 October, 1994: 31–34. Islamic Crafts Series 7. Istanbul: Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA).

Schimmel, Annemarie. 2004. “Creativity in the Art of Calligraphy.” Creativity and Crafts in the Muslim World: Proceedings of the International Seminar on Creativity in Islamic Crafts, Islamabad, 10–12 October, 1994: 17–29. Islamic crafts Series 7. Istanbul: Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA).

Stevens, John. 1981. Sacred Calligraphy of the East. Boulder: Shambala.