The Politics of Library Science in Weimar Germany

The Eichler-Harnack Exchange

Abstract: In 1923, the famous theologian-librarian Adolf von Harnack responded to an essay written by Ferdinand Eichler, Director of the University Library at Graz, titled “Library Science as Science of Value, Library Politics as World Politics.” In the exchange, the two librarians took opposing sides in a discussion about the purpose of academic libraries and collection development. Eichler’s idealistic and universalist approach saw librarianship as a “science over the sciences” that held a unique responsibility for world culture through its responsibility for books. Harnack, on the other hand, took a more pragmatic approach and recognized the limitations posed by political economy to the mission and practices of the library. Although published a century ago, the political pressures and vocational ideals discussed in these essays remain surprisingly relevant for theological librarianship. This paper highlights Harnack’s underappreciated role as the director of the Royal Prussian Library, discusses the Eichler-Harnack exchange, and introduces excerpts from the two essays translated into English for the first time.

In 1939, Felix E. Hirsch, then a librarian at Bard College, wrote an essay in memory of Adolf von Harnack for The Library Quarterly titled “The Scholar as Librarian,” in which he recounted important biographical details of the legendary historian’s life, especially as they related to his service as the director of the Prussian Royal Library. In a section on Harnack’s theory of library science, Hirsch writes that “in a long and pungent essay which contains the kernel of his philosophy of librarianship, he objects to the exaggerated ideas about his profession which were held by the Austrian librarian, Eichler. Library science, Harnack felt, was not a superscience” (Hirsch 1939, 316). Harnack’s essay borrowed its title from the pamphlet to which it responded, “Library Science as Science of Value, Library Politics as World Politics,” by Ferdinand Eichler (1923), Director of the University Library at Graz. In reading these essays, we gain an understanding of two opposing viewpoints on the nature of librarianship from the Weimar Republic, which still read as quite contemporary, despite their age. Many of the political critiques and questions about how and whether librarianship constitutes a science are still discussed today, and often on very similar terms. Following a historical introduction to the Eichler-Harnack exchange are translated excerpts from the two essays.

Ferdinand Eichler’s initial pamphlet was written in April of 1923. Harnack’s response was published as an essay in the Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen, an important library journal associated with the State Library of Berlin (Breslau 1990). The essays deal with questions about the philosophy of librarianship, and so they speak for themselves to a certain extent. But behind their theoretical discussions stood fascinating lives and complex histories that are worth investigating.

Biographical Context

Within theological circles, Harnack is well known as a champion of liberal, scientific approaches to Protestant theology at the turn of the twentieth century. His most widely read book, What is Christianity? sought to identify an essence of the faith, a kernel at the heart of the husks of historical developments. He published a famous multi-volume History of Dogma, studies of the expansion of early Christianity, an important study of the early heretic Marcion, and, significant for theological librarians, Über den privaten Gebrauch der Heiligen Schriften in der alten Kirche, a study of literacy and the private reading of the Bible in late antiquity.

Beyond his prolific career as a theologian and church historian, though, Harnack was one of the most celebrated German scholars of the twentieth century and played an integral role in shaping the modern European academic world. He was the founding head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Societies, now known as the Max Planck Institutes. (Max Planck himself succeeded Harnack in this position.) And, most relevant for our consideration, Harnack served as General Director of the Prussian Royal Library from 1905–1921.

Ferdinand Eichler is not nearly as well-known, and yet Eichler also had an influential career as a philologist and a librarian and deserves to be much more widely read than he is (Zvonar 2003a 19–32; Zvonar 2003b). Unlike Harnack, who was a theologian turned librarian, Eichler spent his entire career in librarianship, and taught and researched in the field of library science. He wrote a programmatic text on The Concept and Task of Librarianship in 1894 and on Library Politics at the End of the Nineteenth Century in 1897, both themes that will resurface in the 1923 essay. Eichler also, like Harnack, was engaged with manuscript studies. While Harnack mostly worked with early church manuscripts, Eichler’s period of specialization was early modern literature. Exemplary of this work was his 1908 study of a Bible copied by Erasmus Stratter, a fifteenth-century scribe, and held by the Graz library.

Historical Context

The period after World War I and the 1918 Revolution was, unsurprisingly, extremely volatile in Germany, but there were also important developments in the academy. Friedrich Althoff served as the minister of education during these years and developed what came to be known as the “Althoff System.” Germany was perceived to be behind the United States and nations of western Europe, and Harnack and Althoff both pushed for the development of the research university as we know it today.

Upon his appointment at the Prussian Royal Library, Harnack needed to prove himself as the new General Director; he was not a trained librarian, although he was a recognized scholar and administrator. He very effectively lobbied for an increase in the library’s budget, though. He established book circulation for the first time at the institution—previously it was entirely non-circulating—in hopes of improving research outcomes. And during his tenure, a new library building was constructed (Hirsch 1939, 300, 311).

Finally, an important aspect of librarianship in Germany more generally that is alluded to in the essays was the development of the Deutsche Bücherei just before World War I. The Bücherei was a library program based in Leipzig that sought to collect, exhaustively, every book published in the German language from the year 1913 forward. This project is still underway today, now called the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, based in both Leipzig and Frankfurt. Harnack actually opposed this project, or at least rejected its philosophy as a model for the research university (Hirsch 1939, 308). Not every book needed to be in a research collection, and on the other hand, a research collection always needed to be international in scope. It couldn’t simply collect German work exhaustively, and neglect work in other languages. This was a rival model that was being developed at the time. A century later, the Bücherei coexists with more traditional research library models.

As mentioned previously, Harnack needed to prove himself as a library director, and did this in an extremely effective manner. He was known to only be on the library premises for one or two hours a day and spent most of his time advocating for it with stakeholders (Hirsch 1939, 306). Harnack was meticulous about what we would today call assessment and completed significant reports on the library collection. Harnack is also known for his concept of a “political economy of librarianship”; he spoke of professors of librarianship as a part of the national economy, describing them as “geisteswirtschaftlichen”—which roughly translates to what we would refer to as the “knowledge economy” today (Harnack 1921; Umstätter 2009, 328–9). This practical and quantitative approach to librarianship is part of what Eichler was objecting to in his more idealistic approach.

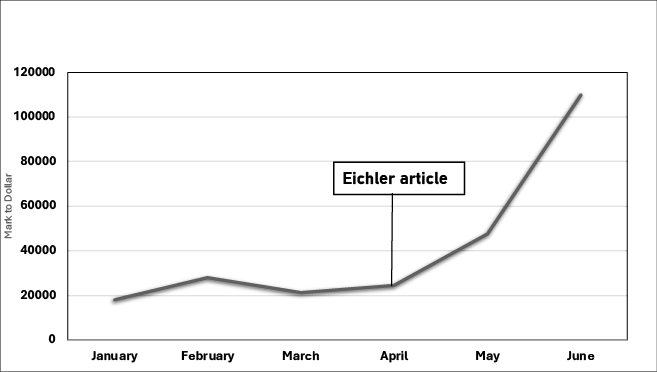

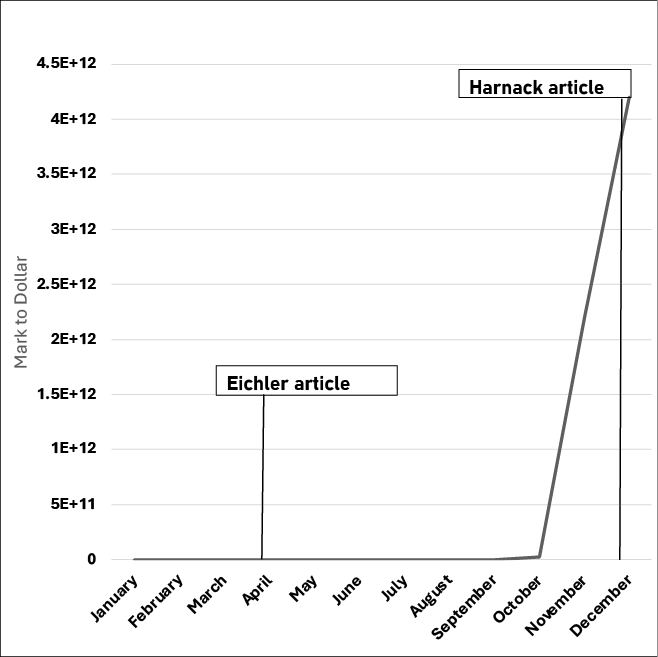

It is difficult to overstate how volatile a year 1923 was for Germany. The Ruhr Valley was taken by French occupation forces at the beginning of the year. Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch occurred in November. And throughout 1923, devastating hyperinflation rocked German society. The following charts visualize monthly average exchange rates for the paper mark, an economic indicator that is not insignificant for considerations related to library management. We see that already at the beginning of the year the mark was nearly worthless—in January the rate was almost 18,000 marks to the dollar. By the time Eichler published his essay on librarianship, this had risen to 25,000 marks to the dollar (see figure 1). And beginning in late summer, inflation was so out of control that the steady climb from earlier in the year looks like a flat line (see figure 2). By the time Harnack published his response to Eichler in December, the exchange rate was over four trillion marks to the dollar. It is incredible that this material context hardly factors into the conversation of these two essays. Eichler’s situation in Austria would have been somewhat better than Harnack’s in Germany, but they also experienced devastating inflation in 1921. Certain individuals and institutions with international connections were relatively sheltered from the worst consequences of hyperinflation. But it is still difficult to imagine how these libraries continued to function on a day-to-day basis.

Translation Excerpts

As the title of these essays suggests, both Eichler and Harnack sought to define library science and library politics. Following are excerpts from my translation of the two essays.

Eichler on library science:

Given the infinite diversity of intellectual products, which arise day after day and find their way to the general public, the question concerning the worth of these products individually and as a collection cannot be ignored. We need to make its assessment a science, which as a science of values is disinterested in individual literary trends, objective, and equipped with critical resources, [and] which also makes use of other empirical sciences, standing over the intellectual chaos and seeking to master it. We name this science today by a century old concept, Bibliothekswissenschaft. We call it this because the place of the collection of literature, the library, is also literature’s birthplace, because the elements which form the conditions for its development—writing, and the book with its changing forms of appearance alternating over time—derive their ultimate meaning in the library and its effectiveness.... In its defining features, it is a science of value, that is, a science of the intellectual values laid down in the literature. If you wanted to express its essence in as concise a definition as possible, you could say: library science is the investigation of literary monuments with regard to the conditions, the nature, and the consequences of their creation, their dissemination, and their use. Its goal, just like every other science, is to know the truth, which in this case is the truth of the value of literary monuments. (Eichler 1923, 6–7; emphasis mine)

Harnack on library science:

“Library Science as Science of Value”—here I must stop already. The highly debatable “library science” certainly also has to do with value judgments—which human science does not?—but this is not characteristic of it.

When the poet stepped before Zeus, the world was already divided; likewise, if the librarian steps before Science, he finds it already assigned to particular scientific disciplines. No, Eichler pleads: he says that it is a “science over the sciences.” But if there really is such a science, it has long been in the hands of the philosophers, or rather the sociologists, and they don’t think at all about relinquishing or parceling out the task given to them. What remains, then, of library science?

Library science, enlivened by the love of books, is the sum of the knowledge of the library and the book in itself—one can also call it a science—out of which comes the art of finding, collecting, conserving, and showing interested parties how to use books for themselves. The final purpose is the primary and ultimate purpose of this “science”—it is altogether focused upon service. (Harnack 1923, 532–3; emphasis mine)

Eichler on library politics:

And this new world of facts appears in library politics, which we have to consider from the standpoint of world politics. The goal of this world politics appears to be worldview.

By library politics we understand the practical application of the principles of the value of literary monuments researched by library science. (Eichler 1923, 11)

Harnack on library politics:

The librarian should chart his course on the basis of the guidelines 1) that the library must let its sun shine “on the good and bad,” 2) that on the other hand following the real current rate of research, it allow as much space as possible for the works of genius and the great talents, and 3) that it must consider the needs of posterity, since nobody else considers this.

In this way the transition from selection to library politics is established. If selection determines library politics, it cannot be more determined than has been remarked here; because what will become of libraries, if here the liberal, there the conservative, here the old-fashioned, there the modern, here the materialist, there the vitalist, here the Catholic, there the dissident, etc., has the greatest say? (Harnack 1923, 535–6; emphasis is mine)

References

Breslau, Ralf. 1990. “Das ‘Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswessen’ in der Weimarer Republik.” Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie 37: 223–238.

Eichler, Ferdinand. 1923. Bibliothekswissenschaft as Wertwissenschaft, Bibliothekspolitik as Weltpolitik. Graz and Leipzig: Leuschner und Lubensky.

Feldman, Gerald D. 1977. Iron and Steel in the German Inflation, 1916–1923. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Harnack, Adolf von. 1921. “Die Professur für Bibliothekswissenschaften in Preussen.” Vossische Zeitung (24 July.)

Harnack, Adolf von. 1923. “Bibliothekswissenschaft as Wertwissenschaft, Bibliothekspolitik as Weltpolitik.” Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen 40 (12): 529–537.

Hirsch, Felix. 1939. “The Scholar as Librarian: to the memory of Adolf von Harnack.” The Library Quarterly 9: 299–320.

Umstätter, Walther. 2009. “Bibliothekswissenschaft im Wandel, von den geordneten Büchern zur Wissensorganisation.” Bibliothek 33 (3): 327–32.

Zvonar, Ivica. 2003a. “Austrijski Teoretičar Knijižničarstva Ferdinand Eichler (1863–1945).” Vjesnik bibliotekara Hrvatske 46 (3–4): 19–32.

Zvonar, Ivica. 2003b. “Croatian Librarian Ivan Kostrenčić: From Vienna to Zagreb.” Geistes-, sozial-und kulturwissenschaftlicher Anzeiger 154 (12): 5–36.